Difference between revisions of "1831: Here to Help"

(→Transcript) |

(→Explanation) |

||

| Line 16: | Line 16: | ||

In the first place, the satire apparently refers to the mathematical/informatical definition of a "hard problem" (see [[#Trivia|below]]) and its confusion with its trivial understanding as well as to a common misunderstanding about verification/falsification. The plot is that Cueball is an enthusiastic and optimistic programmer but obviously a bad informatics guy because he apparently does not know what a "hard problem" is and mixes up the lack of a successful falsification/disproof that a problem is "hard" with a verification/proof. Actually, the formal proof that a problem is "hard" would not be a fail, but an "epic win" (well, maybe not for the disappointed Cueball). | In the first place, the satire apparently refers to the mathematical/informatical definition of a "hard problem" (see [[#Trivia|below]]) and its confusion with its trivial understanding as well as to a common misunderstanding about verification/falsification. The plot is that Cueball is an enthusiastic and optimistic programmer but obviously a bad informatics guy because he apparently does not know what a "hard problem" is and mixes up the lack of a successful falsification/disproof that a problem is "hard" with a verification/proof. Actually, the formal proof that a problem is "hard" would not be a fail, but an "epic win" (well, maybe not for the disappointed Cueball). | ||

| + | |||

| + | This may also be referencing IT support call centres ([[806: Tech Support]]), who often act as though complex computer problems can be solved with clichèd solutions such as 'turn it off and back on again'. | ||

This comic may also be a subtle reference to [[793: Physicists]]. | This comic may also be a subtle reference to [[793: Physicists]]. | ||

Revision as of 18:31, 2 May 2017

| Here to Help |

Title text: "We TOLD you it was hard." "Yeah, but now that I'VE tried, we KNOW it's hard." |

Explanation

| |

This explanation may be incomplete or incorrect: Is the hard problem explanation relevant? The main part of that explain has been moved into a trivia for easier reading to the conclusion at least. If you can address this issue, please edit the page! Thanks. |

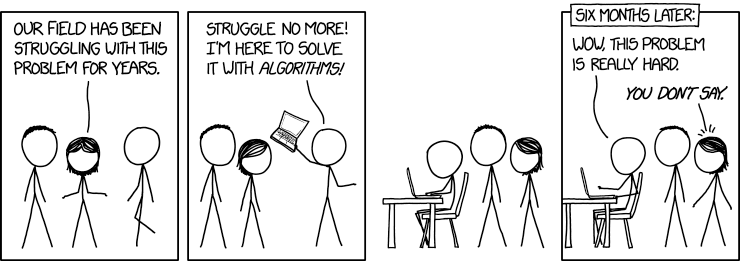

This comic is a satire of computer programmers, who sometimes forget that not everything can be solved with an algorithm. In the first panel, Megan talks about how the field that she and Hairy works in has a difficult problem that many people have been working on. Cueball, believing that algorithms can solve their problem, tries to help. In the next panel, Megan and Hairy silently watch Cueball working on the problem on his laptop. Finally, six months later, Cueball concedes, and an exasperated Megan retorts sarcastically, pointing out that she had explained its difficulty six months ago with the timeline.

The title text furthers Cueball's apparent arrogance by showing a dialogue. Megan or Hairy says, "We TOLD you it was hard," referring to the first panel, but Cueball, still confident in his own ability's superiority, says, "Yeah, but now that I'VE tried, we KNOW it's hard." The joke is that Cueball believes that, even though he has just failed, it was his attempt which proved the difficulty, and not Megan and Hairy's work for years. The dialog references an exchange from the recent film The Imitation Game, in which Alan Turing's superior claims, "The Americans, the Russians, the French, the Germans, everyone thinks Enigma is unbreakable." and Turing replies, "Good. Let me try and we'll know for sure, won't we?"

The satire, however, applies far beyond computer programmers. It can be read as a political commentary, like in Nobody knew health care could be so complicated. It is what we'd all like to see when well-meaning advice givers provide the "simple" solution to all our problems, or management provides glib advice from ten thousand feet. It is a commentary on the universal tendency to see problems as simple because we don't know what makes them hard.

In the first place, the satire apparently refers to the mathematical/informatical definition of a "hard problem" (see below) and its confusion with its trivial understanding as well as to a common misunderstanding about verification/falsification. The plot is that Cueball is an enthusiastic and optimistic programmer but obviously a bad informatics guy because he apparently does not know what a "hard problem" is and mixes up the lack of a successful falsification/disproof that a problem is "hard" with a verification/proof. Actually, the formal proof that a problem is "hard" would not be a fail, but an "epic win" (well, maybe not for the disappointed Cueball).

This may also be referencing IT support call centres (806: Tech Support), who often act as though complex computer problems can be solved with clichèd solutions such as 'turn it off and back on again'.

This comic may also be a subtle reference to 793: Physicists.

Transcript

- [Megan, standing next to Hairy, is addressing the reader holding her arms out. Cueball walks in from the right.]

- Megan: Our field has been struggling with this problem for years.

- [Cueball holds his laptop high up in one arm above Megan's head while holding his other arm out as well. Megan has turned to look at him.]

- Cueball: Struggle no more! I'm here to solve it with algorithms!

- [In a frame-less panel Cueball sits on a chair at a desk with his laptop working on it, while Hairy and Megan looks on from behind.]

- [Cueball, still sitting at his laptop, points at the screen. Megan raises her arms and four small lines above her head, on either side of her speech line, indicate her annoyance with Cueball.]

- Six months later:

- Cueball: Wow, this problem is really hard.

- Megan: You don't say.

Trivia

- Hard problem:

- The trivial understanding of a "problem" is any random task like "make me a webpage" and a "hard problem" means "it takes much effort to solve it". However, the informatical definition of a "problem" is a formal description of a task like "find me the password to a given hash (with a length of N bits)" so it can be solved with an algorithm, i.e. a formal mathematical "how-to" or a piece of program code. A "hard problem" is a problem which can only be solved by "brute force", that means (in this example) you have to try every possible password (2^N possibilities) and check whether its hash matches the given one. A "simple problem" is a one where a "short-cut" algorithm to the "brute force" method exists. There are problems which can be formally proven to be "hard" but, unfortunately, most problems like breaking a certain encryption algorithm can only be hoped to be "hard" or at least not be proven "simple" by finding a "short-cut" too soon. You may prove that a problem is not "hard" by finding such a "short-cut" but you cannot prove it is "hard" by trying and failing (the fact that you didn't find a "short-cut" does not mean there is none).

Discussion

So who else read the "Six months later" caption in the voice of the French narrator from SpongeBob Squarepants? 172.68.58.41 23:26, 1 May 2017 (UTC)

Gosh, is Randall making a parallel to someone else who only recently announced that his job is hard, and that nobody knew how complicated things could be? Seems like a clear poke at Trump to me. 108.162.246.23 23:43, 1 May 2017 (UTC)

- EVERYONE feels like that after the election. Get over it. That's right, Jacky720 just signed this (talk | contribs) 23:50, 1 May 2017 (UTC)

Between algorithms and "objectively" establishing that a problem is hard, I took this to be a reference to https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/NP-hardness … --162.158.222.16 00:31, 2 May 2017 (UTC)

- While the people originally having the problem (Megan and Hairy in this case) may not appreciate it (because it wouldn't help SOLVING the problem), establishing that some problem is not only "hard" but specifically NP-hard, AI-hard, equivalent to halting problem or for example equivalent to axiom of choice is important scientific result. -- Hkmaly (talk) 02:03, 2 May 2017 (UTC)

Rather than referencing The Imitation Game, the sentence "[...] now that I'VE tried, we KNOW it's hard." may be referencing instead Awakenings (1990), where Robin William's character says something similar near beginning of the movie.

Regarding the (possible) reference to the Imitation Game, whilst it may be true that the Americans Russians French and Germans thought Enigma unbreakable, the Polish had been breaking it for years before Turing got involved and work done in Poland was an important part of the British success early in the war. German improvements to operating practices later stopped the Polish methods working and yes Turing had better methods that still worked, later on in the war. But Poland at least, didn't think it was unbreakable. Just saying.

- While we are "just saying". The Germans were well aware that the Enigma was breakable, they just figured it would be too much effort. It really was, the total resources pored into breaking the Enigma was on par with the Manhattan project and the moon landing (ie US space program during the 1960s). The Germans did some changes to increase security during the war, but had they suspected how completely Enigma was broken they would probably have abandoned it. 172.68.182.202 17:50, 4 May 2017 (UTC)

I think the whole paragraph about informatics at the bottom is missing the point. That explanation is based on the premise that Cueball was told the problem was a "hard problem" (a formal type of problem) and didn't understand. Megan never used the formal term "hard" in describing the problem. She merely said that her field had struggling for years.162.158.79.5 13:13, 2 May 2017 (UTC)

- Agreed — she uses "hard", but later in the title text. What's still true is that the problem might still have a solution that is "simple" (you can explain it in a paragraph) but hard-to-find (it took decades to find it), and they haven't proved that's not the case. But most would still call a problem with such a solution "hard".

- Worse, as a PhD student in CS (programming languages), I'm pretty sure "hard problem" in CS also mean the same as in everyday life—"Boy, this research problem is really hard"—as opposed to NP-hard (which is what the description is attempting to describe in an extremely informal way. I've honestly never heard anybody use "hard" for "NP-hard", though that appears used on https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Computational_complexity_theory#Hard. Meanwhile, I went ahead and deleted "Set of algorithms" since that was even less relevant (and didn't bother arguing relevance). http://www.explainxkcd.com/wiki/index.php?title=1831:_Here_to_Help&diff=139534&oldid=139519. --Blaisorblade (talk) 14:26, 3 May 2017 (UTC)

- Yeah, but we're shown some arbitrary problem which Cueball is solving not with Bayesian Inference, or Object Oriented Programming, or String Theory, but with Algorithms -- the one technique where showing something is hard is a formal term. It would be quite a coincidence if this happened by accident.

The current explanation is taking a too tactical or literal approach. Throughout history computer science has presented itself as a solution to a variety of hard problems in other fields using a variety of techniques. These include AI, machine learning and now, big data. In most cases the techniques enter with a lot of fanfare, but later flame out, producing no real gains towards solving the hard problem. For example see all the things that computers were promising back in the 1960's. Cueball simply represents a generic version of these past and present CS fads. Sturmovik (talk) 15:42, 2 May 2017 (UTC)

Fixed: Throughout [most of] history computer science has [not existed].