Difference between revisions of "1266: Halting Problem"

m (Fix the incomplete template to point to the correct page) |

(Consolidate the explanation to a single, hopefully coherent, phrasing.) |

||

| Line 9: | Line 9: | ||

==Explanation== | ==Explanation== | ||

{{incomplete|1266: Halting Problem}} | {{incomplete|1266: Halting Problem}} | ||

| − | In 1936 {{w|Alan Turing}} proved that it's not possible to decide whether an arbitrary program will eventually halt, or run forever. This was later called the {{w|Halting problem}} by {{w|Martin Davis}}. | + | In 1936 {{w|Alan Turing}} proved that it's not possible to decide whether an arbitrary program will eventually halt, or run forever. This was later called the {{w|Halting problem}} by {{w|Martin Davis}}. The official definition of the problem is to write a program (actually, a {{w|Turing Machine}}) that accepts as parameters a program and its parameters. That program needs to decide, in finite time, whether that program will ever halt running these parameters. |

| − | The halting problem is a cornerstone problem in computer science. | + | The halting problem is a cornerstone problem in computer science. It is used mainly as a way to prove a given task is impossible, by showing that solving that task will allow one to solve the halting problem. |

| − | + | [[Randall]], however, is providing a simpler solution. He implements his own code for the question ''"Does it halt?"'' which always returns a positive answer, directing us to look at the bigger picture. | |

| − | + | For all '''practical''' purposes, this is the correct solution. Given enough time, any program will halt. This is due to factors external to the actual program. Sooner or later, electricity will give out, or the memory containing the program will get corrupted by cosmic rays, or corrosion will eat away the silicon in the CPU. Nothing lasts forever, and this includes a running program. | |

The title text further relates to this issue by claiming to have found a case where something need not die, but Randall does not know how to actually show it to anyone. | The title text further relates to this issue by claiming to have found a case where something need not die, but Randall does not know how to actually show it to anyone. | ||

| + | |||

| + | It should be noted that Randall's solution does not, in fact, solve the halting problem. The halting problem requires two parameters (a program and its parameters), while Randall's function only accepts one. His solution does not match the interface required by the problem. | ||

==Transcript== | ==Transcript== | ||

Revision as of 08:15, 18 September 2013

| Halting Problem |

Title text: I found a counterexample to the claim that all things must someday die, but I don't know how to show it to anyone. |

Explanation

| |

This explanation may be incomplete or incorrect: 1266: Halting Problem If you can address this issue, please edit the page! Thanks. |

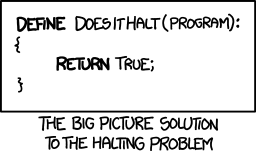

In 1936 Alan Turing proved that it's not possible to decide whether an arbitrary program will eventually halt, or run forever. This was later called the Halting problem by Martin Davis. The official definition of the problem is to write a program (actually, a Turing Machine) that accepts as parameters a program and its parameters. That program needs to decide, in finite time, whether that program will ever halt running these parameters.

The halting problem is a cornerstone problem in computer science. It is used mainly as a way to prove a given task is impossible, by showing that solving that task will allow one to solve the halting problem.

Randall, however, is providing a simpler solution. He implements his own code for the question "Does it halt?" which always returns a positive answer, directing us to look at the bigger picture.

For all practical purposes, this is the correct solution. Given enough time, any program will halt. This is due to factors external to the actual program. Sooner or later, electricity will give out, or the memory containing the program will get corrupted by cosmic rays, or corrosion will eat away the silicon in the CPU. Nothing lasts forever, and this includes a running program.

The title text further relates to this issue by claiming to have found a case where something need not die, but Randall does not know how to actually show it to anyone.

It should be noted that Randall's solution does not, in fact, solve the halting problem. The halting problem requires two parameters (a program and its parameters), while Randall's function only accepts one. His solution does not match the interface required by the problem.

Transcript

Define DoesItHalt(program):

{

return true;

}

- The big picture solution to the halting problem.

Discussion

I wrote an explanation for the body of the comics, but I believe there are aspects of the title I'm still missing, so I left the incomplete tag in place. Shachar (talk) 07:52, 18 September 2013 (UTC)

Isn't google already running applications designed to continue running even if some of nodes they run on have a fatal hardware failure? Also, even if the claim would be true in "practical" sense, it would not solve the problem, because as you said, the stopping would be because of reasons external to the actual program. In other words, program running on turing machine will never stop by hardware failure, because turing machine BY DEFINITION doesn't have any. -- Hkmaly (talk) 08:57, 18 September 2013 (UTC)

- Remembered this is wiki and added it to the actual explanation :-) -- Hkmaly (talk) 09:10, 18 September 2013 (UTC)

- Several systems are running with redundant nodes. They will not run forever. They are in for example extremely unlikely to outlive the sun. 85.19.71.131 11:29, 18 September 2013 (UTC)

- System with ability to replace nodes can be deployed on nodes physically as distant as needed. Application which is currently starting on a multi-node system on earth can be later expanded to system with nodes in different star system. Although unless the nodes have FTL connection it would have inpractically large lag ... -- Hkmaly (talk) 09:39, 20 September 2013 (UTC)

"For all practical purposes, this is the correct solution"

- No, it's not. A very practical purpose would be "have my OS kill processes that won't stop". Other one would be "reject installing apps that contain algorithms that don't halt". If the OS assumes "every app will eventually halt" it would kill every process and reject every app. Osias (talk) 12:15, 18 September 2013 (UTC)

- Changing the paragraph to say "a physical perspective" instead of "all practical purposes" was a good solution. Osias (talk) 14:16, 18 September 2013 (UTC)

- It would, in fact, kill/reject none since it would find no nonhalters.178.0.89.106 20:51, 18 September 2013 (UTC)

Google "halting problem" and do a little reeding so you are in the same mindset as Randall. This is a famous computer science problem. You aren't talking about the same thing in comments above. — tbc (talk) 12:30, 18 September 2013 (UTC)

What is the joke here? What does "big picture" mean? 62.209.198.2 16:33, 18 September 2013 (UTC)

- I believe it's related to the quote " In the long run we are all dead." by John Maynard Keynes. Osias (talk) 18:46, 18 September 2013 (UTC)

- Alternatively, "big picture" people aren't really concerned with details. "You want to know if it halts? I'm telling ya baby, it halts!" The value of such an assertion is dubious, but it does save a lot of worrying. You know what else is funny? The mind-numbing amount of detail in these responses to a comic about the the "big picture". Reflect, people, reflect! 108.162.219.58 23:04, 4 February 2014 (UTC)

Same kind of humor as in http://www.explainxkcd.com/wiki/index.php?title=221 176.67.13.14 18:47, 18 September 2013 (UTC)

A program with its given input can be seen, as a whole, as a specific program. Therefore the halting function need not take two inputs and is equivalent to a function that takes the two described inputs. Therefore I feel the comment about the number of inputs in the explanation can be removed. 66.69.243.27 (talk) (please sign your comments with ~~~~)

- Yeah, the halting problem on the empty word/input is known to be equivalent to the general halting problem. I think that's the form used in this comic. 85.218.82.16 (talk) (please sign your comments with ~~~~)

Might there be a reference here to Isaac Asimov's famous story "The Last Question"? (The titular question was: 'Can entropy be reversed?' Throughout the lifetime of the universe, the computer only said: 'THERE IS INSUFFICIENT DATA FOR A MEANINGFUL ANSWER.') 174.239.229.68 04:18, 20 September 2013 (UTC)

- Missing the obvious?

Maybe it is just me, but I interpreted this to be the "DoesItHalt" function actually *running* "program", then when "program" completes (halts) it returns true. This would be the "big picture" solution and does not actually deal with the "details". --B. P. (talk) 23:52, 20 September 2013 (UTC)

What you thought you saw was the most obvious "implementation" of a solution to the halting problem.

define DoesItHalt (program):

{

program();

return true;

}

This solution returns true if program stops, and loops forever is program loops forever. Xhfz (talk) 20:44, 23 September 2013 (UTC)

- It won't work if your program is exit() or shutdownYourComputer(). :) --61.223.87.164 00:49, 28 September 2013 (UTC)

- Turing machines are known to be really poor at I/O. If you trace the shutdownYourComputer function, it actually instructs your power supply unit (ATX required, AT lacked such capability) to turn power down. Similarly, rebootYourComputer function instruct outside hardware - usually north bridge - to send a reset signal on the PCI bus (and presumably other busses), which will reset all devices and start POST. Unlike Turing machines, virtualized OSs may be able to reboot host computer if the hypervisor is not coded correctly and allows I/O for hardware acceleration. -- Hkmaly (talk) 09:22, 16 October 2013 (UTC)

- Irrelevant load. Randall is not concerned with multiple nodes or hypervisors, he is simply demonstrating the "big picture" solution to an undecidable problem in computing. It is *not possible* in general to determine if 'program' will halt or not, so don't even look at it. Sidestep the work and just return your best guess. That's how people frequently operate, right? 108.162.219.58 23:04, 4 February 2014 (UTC)

- The halting problem for every input

The sentence in bold is false

- It should be noted that Randall's solution, barring its unsoundness, solves more than the halting problem in the form it is usually stated. The halting problem requires two parameters (a program and its parameters), while Randall's function only accepts one (the program). The question of whether a program halts for every input can be shown to be even harder to solve than the halting problem, meaning that even if a Turing machine had an additional instruction allowing it to check whether a program halts with given parameters, it still could not always confirm that a given program that halts for all parameters does so.

In fact, let A be a Turing machine that solves the halting problem for one input, and B a Turing machine that solves the halting problem for every input. B can be built using A as a subroutine. First B builds machine Y that takes its input, X, and halts if X loops with at least one input; Y loops if X stops for every input.

- Turing machine B (Turing machine X) {

- // manipulate X in order to build Y that calls X for every input and stops when the first input does not halt

- Y =

"s = ''; repeat { if (A(" + X + "," s + ") == 'false' then halt; s = next(s);}" - return A(Y, "") // second parameter is ignored

- }

The function next returns the next valid string. For example, if our alphabet is A..Z0..9, then next("AJ38YT") = "AJ38YU"

Machine B determines if Y halts. And Y halts if machine X does not halt. If we had Turing machine A then we could build B. Xhfz (talk) 17:53, 18 October 2013 (UTC)

- There is a problem with this argument. What you have shown is that if there exists an algorithm A that solves the halting problem, then there is an algorithm B that solves the "all-input-halting-problem". However, the all-input-halting-problem is harder in the following sense: Given an oracle (i.e., some "magic" machine that gives the correct answer even though there exists no algorithm for doing so) for the halting-problem, you cannot solve the all-input-halting-problem. But given an oracle for the all-input-halting-problem, it is easy to solve the halting problem. (Your proof does not contradict this, because if A is an oracle, then Y is not a Turing machine and cannot be fed to A.) Basically, the all-input-halting-problem is one step higher on the arithmetical hierarchy (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Arithmetical_hierarchy). 172.69.138.46 22:24, 10 March 2019 (UTC)

- Karl Popper

I think that the title text is a direct reference to Karl Popper's falsifiability argument, since this is one of the most common example of a non-falsifiable statement. Bonob (talk) 19:01, 18 October 2013 (UTC)

- Popper claimed that such things are outside the realms of science, correct? The undecidability of this question has been used to falsify other intended scientific proofs. Therefore, it is surely within the realms of science. 108.162.219.58 23:04, 4 February 2014 (UTC)

- Bad example for showing the difference between theoretical computation and "actual" computation

The explanation's "1/3 + 1/3 + 1/3 = 1" example ticks me off: symbolic math programs can already give the correct answer to this easily. See http://www.sympygamma.com/input/?i=1%2F3+%2B+1%2F3+%2B+1%2F3 . 108.162.229.53 (talk) (please sign your comments with ~~~~)

- You're misunderstanding it. "1/3 + 1/3 + 1/3 = 1". You won't -always- get 1 using every implementation. But the answer is always 1. What a computer outputs and what the truth is are not -always- the same thing. It wasn't implied that they are -never- the same thing. It's only a bad example if you always get "1/3 + 1/3 + 1/3 = 1". 162.158.145.84 (talk) (please sign your comments with ~~~~)