Difference between revisions of "1526: Placebo Blocker"

(→Explanation) |

m (→Transcript) |

||

| Line 25: | Line 25: | ||

:Cueball: Some researchers* are starting to figure out the mechanism behind the placebo effect. | :Cueball: Some researchers* are starting to figure out the mechanism behind the placebo effect. | ||

:Cueball: We've used their work to create a new drug: a ''placebo effect blocker.'' | :Cueball: We've used their work to create a new drug: a ''placebo effect blocker.'' | ||

| − | :Footnote: * Hall et al, DOI: [ | + | :Footnote: * Hall et al, DOI: [http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/J.MOLMED.2015.02.009 10.1016/J.MOLMED.2015.02.009] |

:Cueball: Now we just need to run a trial! We'll get two groups, give them both placebos, then give one the ''real'' placebo blocker, and the other a... | :Cueball: Now we just need to run a trial! We'll get two groups, give them both placebos, then give one the ''real'' placebo blocker, and the other a... | ||

:Cueball: ...wait. | :Cueball: ...wait. | ||

Revision as of 09:21, 18 May 2015

| Placebo Blocker |

Title text: They work even better if you take them with our experimental placebo booster, which I keep in the same bottle. |

Explanation

| |

This explanation may be incomplete or incorrect: Stub If you can address this issue, please edit the page! Thanks. |

The placebo effect refers to the phenomenon where patients which are given an inactive treatment (such as a sugar pill) but told that they are receiving an effective treatment can still show improvement relative to an untreated patient. The placebo effect is important to consider for experiments to test whether new drug treatments are effective, since even ineffective treatments can lead to improved outcomes. Thus, modern drug trials are conducted as double blind experiments, where patients are randomly given either the treatment or a placebo without either them or the administering doctors knowing which is which.

Several reasons for the placebo effect have been proposed, from study artifacts such as under-reporting of negative outcomes by patients who think they are being treated, to neurological explanations for how mental state can translate into physical outcomes. This comic refers to a study published this month about possible mechanisms for the placebo effect:

- Kathryn T. Hall, Joseph Loscalzo, and Ted J. Kaptchuk. (2015) Genetics and the placebo effect: the placebome. Trends in Mol Medicine. Volume 21, Issue 5, May 2015, Pages 285–294 doi:10.1016/j.molmed.2015.02.009

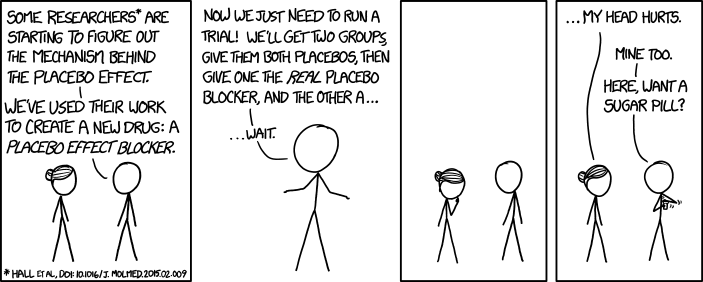

Cueball announces the creation of a drug designed to prevent the placebo effect from occurring. The joke centers around the difficulty in designing an experiment which would test whether such a drug worked. Following the typical experimental design, patients experiencing the placebo effect (i.e. who had just taken a placebo and been told it was a treatment for some ailment) would be split into two groups. The first group would receive the blocker drug, while the second would receive a placebo. However, Cueball then trails off after realizing the problems with such a scheme, such as the fact that one group receives two different placebos, or that it is unclear how the patients could be told what the drug was designed for without negating the effect of the original placebo.

After Hair Bun Girl develops a headache from trying to think of a proper experimental design for the placebo blocker, Cueball offers her a sugar pill as a cure. While this might have helped the headache via the placebo effect had he told her it was a headache treatment, by revealing the pill as merely a sugar pill, although it may reduce the effect but still be effective.

The alt-text further complicates the situation by introducing another drug which boosts the placebo effect. Since the placebo booster is kept "in the same bottle" (presumably as the placebo blocker), this suggests that both the booster and the blocker are themselves placebos, and that their efficacy in strengthening or reducing the placebo effect is itself coming from the placebo effect.

Transcript

- Cueball: Some researchers* are starting to figure out the mechanism behind the placebo effect.

- Cueball: We've used their work to create a new drug: a placebo effect blocker.

- Footnote: * Hall et al, DOI: 10.1016/J.MOLMED.2015.02.009

- Cueball: Now we just need to run a trial! We'll get two groups, give them both placebos, then give one the real placebo blocker, and the other a...

- Cueball: ...wait.

- [Hair Bun Girl holds her chin, while Cueball looks towards the ground.]

- Hair Bun Girl: ...my head hurts.

- Cueball: Mine too.

- [Cueball begins to take the lid off of a medicine bottle.]

- Cueball: Here, want a sugar pill?

Discussion

- Placebome

The title of the referenced paper introduces the 'Placebome', the collection of genes which lead to the placebo effect. This is an absolutely ridiculous word, and would be worthy of Jonathan Eisen's Worst New Omics Word Award. Quantum7 (talk) 08:31, 18 May 2015 (UTC)

- Title text bottle

It seems more plausible to me that the "they" and "same bottle" in the title text refer to the sugar pills for headache. The title text would then be an organic continuation of the immediately preceding dialogue. Angew (talk) 09:01, 18 May 2015 (UTC)

- Agreed. Take two sugar pils. The second will boost the effect of the first. It could work if you believe it.--Kynde (talk) 12:14, 18 May 2015 (UTC)

I'm confused about why this explanation is a stub. Personally, I think it explains the comic well, but I'll refrain from removing the incomplete tag in case most people think that the explanation isn't adequate. Caeleste Alarum (talk) 15:21, 18 May 2015 (UTC)

Wouldn't you find a malady that can be treated via placebo, like a headache, give control group A a headache pill, control group B a placebo and tell them it was a headache pill and give the test group a placebo blocker as the placebo and tell them it is a headache pill?

A placebo blocker would be really useful in medical testing to find out which medicines are actually effective and which are simply producing a stronger placebo effect through a noticeable side effect. 173.245.48.125 15:46, 18 May 2015 (UTC)

- How to do it.

Compound two sets of placebos. The control set is just sugar pills. The other set would be the blocker. Unless the active dose is massive, it'd also be partially a sugar pill already.

Present both as a possible treatment for some malady.

Each group would then only get one pill, and be ignorant that there was potentially a placebo blocker in their dose. 108.162.238.160 17:09, 18 May 2015 (UTC)

I would guess that there would have to be at least 6 groups. Groups 1 and 2 would be the traditional experiment with a drug and a placebo, groups 3, 4, 5, and 6 are given two pills one of which they told is a drug, the other is a placebo blocker which may prevent the first drug from helping you. groups 3 and 4 are given the real placebo blocker, groups 5 and 6 are given another placebo. This would be an interesting experiment in that you could test the psychological effects of telling someone who took a real drug that "it may not work." 108.162.238.188 18:36, 18 May 2015 (UTC) Veggiet

I think we've entirely overlooked the idea of using a control group that doesn't know what the word placebo means. With such a control group, one could not tell them any lies at all "I've invented this new drug called placebo that will cure your rheumatism".Seebert (talk) 18:57, 18 May 2015 (UTC)

- Why do you have to include the world placebo? Any new made up name like turgidax or pragmanol or frogans or vulpix or bligdrine will work. What is wrong with saying to the patient in the control group,"You are testing a pill of bligdrine." The patient may or may not know what placebo is, but they will certainly be not aware of bligdrine. 173.245.48.163 20:21, 18 May 2015 (UTC)BK201

I once removed the last paragraph regarding speculations on the title text as of what could happen if there were two different pills in the bottle. But it is to me clear that there is just sugar pills, as is already explained above. And thus this paragraph is overkill. But it was inserted again after I deleted it. I vote for it to be deleted, but will let someone else do this, as not to make it a personal edit war... --Kynde (talk) 16:05, 19 May 2015 (UTC)

Here's an experiment done all the way back in 1978: Levine, J.D., Gordon, N.C., and Fields, H.L. (1978). The mechanism of placebo analgesia. Lancet 2: 654-657. Summary: The researchers recruited volunteers who were undergoing tooth extraction. After surgery, one group received morphine-based drugs (most, but not all, reported pain relief). Others received placebo (about a third reported pain relief). Others yet were given placebo AND naloxone, a drug that blocks the action of opioids (none reported pain relief). The researchers concluded that administration of placebo caused the release of endogenous opioids in some patients, and naloxone worked as a placebo blocker. More recent research with functional brain imaging has confirmed that opioids and placebos activate the same brain regions (Petrovic, P., Kalso, E., Petersson, K.M., and Ingvar, M. (2002). Placebo and opioid analgesia imaging--A shared neuronal network. Science 295: 1737-1740).CLSI (talk) 17:07, 19 May 2015 (UTC)

- How to run the experiment

I am going to comment out (but not delete yet) the explanation for how it is "actually quite simple" to test the placebo blocker. I feel that the experiment is flawed in that testing the two drugs simultaneously would potentially impact the results in respect to either one.

The experiment suggests: Group 1 would receive the new drug and a placebo pill; group 2 would receive the new drug and a Placebo Blocker; group 3 would receive two identical placebo pills; and group 4 would receive one placebo pill and one Placebo Blocker.

However, we still don't truly know how placebos work. Are the people in this study told what the second pill is for (a placebo blocker?) maybe that knowledge will negate the placebo entirely. For example, what if in a simple double-blind test of Drug A, the placebo group had the same results as the drug group. However, Drug B (the blocker) doesn't work. In the proposed experiment of both Drug A and Drug B, between Group 1 and Group 3, what if the placebo effect works on Placebo B, and so the placebo effect Placebo A had in the simple experiment is negated. Thus Drug A appears to be effective even though its not better than a placebo.

The bottom line is that it's not that easy to design an experiment to test two variables at once. TheHYPO (talk) 16:07, 25 May 2015 (UTC)

- Headache

The sentence "My head hurts" doesn't mean a headache, but Cueball takes this too literally. It's more like a reaction on some stupid experiments witch hurt my head. --Dgbrt (talk) 20:53, 8 June 2015 (UTC)

I've just gone through the article, fixing grammar. I'm happy that spelling and grammar is good now. However I've also updated the explanation quite a bit; hopefully people agree it's an improvement, but I know a lot of people have taken an interest in this article. Edit or roll back if you like! Cosmogoblin (talk) 23:32, 14 July 2015 (UTC) P.S. In explaining the placebo, the placebo blocker, the placebo blocker placebo ... my head started to hurt too! (Could we have a "placebo-blocker-placebo blocker"? Or would that be taking things too far?)

If I'm thinking about it correctly, then a "placebo-blocker-placebo blocker" would be the same thing as a simple placebo-blocker. The only difference is that while giving them the sugar pill, instead of telling them "this pill will get rid of your headache," you'd be saying "this pill will get rid of your placebo effect." So if the blocker worked, then the patient would NOT be fooled ie they would NOT be convinced that the fake blocker works, which is kind of pointless because you DID end up giving them the blocker afterwards! Ok I agree my head hurts 198.41.235.59 (talk) (please sign your comments with ~~~~)

As of the writing of this comment, there's an incomplete tag. While I agree that it's a bit bigger than necessary, it was good enough for me. However, there are two things that I disagree with (plus the typo that I fixed):

- I don't think the headache is because they're frustrated about not being able to conduct the experiment. I think it's because they're confused about the placebo inception.

- I don't think the sugar pill is meant to cure the headache by placebo. I think it's a comforting action to offer someone a good tasting food when someone's distressed, plus the humor that the pills Cueball's holding are probably his placebo blocker pills and that they're actually sugar pills.

188.114.97.151 22:53, 23 December 2015 (UTC)