2787: Iceberg

| Iceberg |

Title text: 90% of the iceberg is hidden beneath the water, but that 90% only uses 10% of its brain, so it's really only 9%. |

Explanation

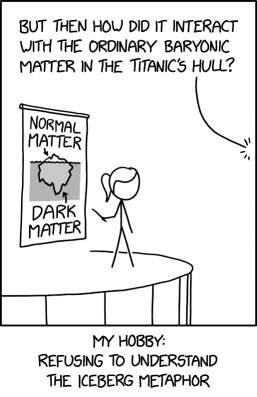

This is another comic in the My Hobby series. The previous comic in this series was 2733: Size Comparisons, released just over 4 months prior. The iceberg metaphor is a famous metaphor sometimes misattributed to Freud. Just as real a iceberg floats with the vast majority of its body below the water's surface (often simplified as 90%, which does quite closely reflect the general range of buoyancy for ice in cold sea-water), the iceberg as metaphor represents a system where the large majority is unseen, invisible, or hidden in some way.

In this case, Ponytail is using it to illustrate the fact that about 95% of the mass in the universe does not appear to be in the form of ordinary ("baryonic") matter, but rather dark matter and dark energy. Dark matter is known to not interact at all with ordinary baryonic matter except by gravity, and has been detected only by its gravitational effects. Excluding dark energy, dark matter accounts for about 85% of the total mass of the universe. So baryonic matter is like the "tip of the iceberg," visible to us above the surface, while dark matter is like the invisible majority of the iceberg below the surface.

The questioner in the audience misunderstands the metaphor by taking it literally, thinking that Ponytail is saying that the part of an iceberg below the surface is literally made of dark matter. He points out that the Titanic sank after its hull was damaged by hitting the underwater part of an iceberg, which wouldn't be possible if it were made of dark matter. Cueball has previously been confused about dark matter in 2186: Dark Matter.

The title text references the myth that we use only 10% of our brain, and we could become more intelligent or powerful by "unlocking" the remaining 90%. If icebergs had brains, and the 90% in the "dark matter" part underwater used only 10% of its brain, while the tip also used 10% of its brain, then most of the cognition would occur in the underwater part. Hence the "9%" figure would refer to the cognition occurring underwater, with 1% of its cognition occurring above water. In reality, human beings use pretty much all of their brain. They just don't use it all at the same time; at any given instant, between 2% and 16% of neurons are firing, depending on how active the brain is in that moment. The effect of using one's whole brain would depend on precisely what is meant by that -- for example, all excitatory neurons firing with no inhibition for a prolonged period would be a seizure (most likely fatal), but there's no reason to exclude inhibitory neurons and adenosine when "using all of one's brain at once".

Transcript

- [Ponytail is standing on a rostrum and pointing to a chart with a stick. The chart depicts a cross section of an iceberg in water, so most of it is underwater, depicted as light gray in dark gray water, but a little is above the surface, depicted in white. There are labels above and below the drawing with two small arrows pointings from above and below to the two segments of the iceberg. An off panel voice speaks from a starburst at the right edge of the panel.]

- Off panel voice: But then how did it interact with the ordinary baryonic matter in the Titanic's hull?

- Upper Label: Normal Matter

- Lower Label: Dark Matter

- [Caption below the panel:]

- My Hobby:

- Refusing to understand the iceberg metaphor

Discussion

Dang! This is really good! Kudos to whomever wrote the explanation so soon. Trogdor147 (talk) 19:48, 9 June 2023 (UTC)

- - Undid ('whoever' because it's the subject of the verb 'wrote'. The 'to' governs the whole phrase, not the single pronoun 'who×m×ever'. KoroNeil.) because it really shouldn't have been reason to edit someone else's comment. Maybe, instead, both of those concerned will read this and learn respective lessons. 172.70.90.253 10:26, 23 June 2023 (UTC)

In other "news" (or should that be "olds"?), we are not using 100% of our muscle power at once either. Because for most muscles, there are muscles for pulling against them in the other direction, and using both at once usually doesn't make any sense. -- Hkmaly (talk) 20:21, 9 June 2023 (UTC)

- And in fact, there are sections of the brain that exist specifically to inhibit other sections of the brain, notably the forebrain. Nitpicking (talk) 03:07, 10 June 2023 (UTC)

- Simulations are pretty clear about this: most of the inhibitory connections in the brain are effectively used to keep the excitatory connections at a state of maximum sensitivity to input signals. (Without them, you'd have a runaway cascade; a seizure.) No, it's obvious that not everything is used at once because we're not actively remembering everything at once; there must be something quiescent most of the time. --162.158.34.21 14:16, 10 June 2023 (UTC)

- Not so, it could be the case that information is constantly moving throughout the brain and our perception of thought is when those neurons pause or rest or else when it moves even faster. We know that this is not how the brain functions, it's just a counterexample to the above comment. 108.162.242.73 13:10, 11 June 2023 (UTC)

- I suppose the seizure claim could be "cited" with this Quora topic, but if you read that you see it has a lot of assumptions. Perhaps we should say something like: They just don't use it all at the same time. The effect of using the whole brain would depend on precisely what is meant by that -- for example, all excitatory neurons firing with no inhibition for a prolonged period would be a seizure, but there's no reason to exclude inhibitory neurons and adenosine when "using all of the brain at once". I also found this recent Science story suggesting it would be like the near-death experience of being everywhere in one's life all at once -- and if you saw that film you just might think it's like having superpowers. Mrob27 (talk) 19:12, 12 June 2023 (UTC)

- Not so, it could be the case that information is constantly moving throughout the brain and our perception of thought is when those neurons pause or rest or else when it moves even faster. We know that this is not how the brain functions, it's just a counterexample to the above comment. 108.162.242.73 13:10, 11 June 2023 (UTC)

- Simulations are pretty clear about this: most of the inhibitory connections in the brain are effectively used to keep the excitatory connections at a state of maximum sensitivity to input signals. (Without them, you'd have a runaway cascade; a seizure.) No, it's obvious that not everything is used at once because we're not actively remembering everything at once; there must be something quiescent most of the time. --162.158.34.21 14:16, 10 June 2023 (UTC)

Also, how does dark matter produce buoyancy if it doesn't interact with water? 172.69.247.50 15:10, 11 June 2023 (UTC)

- Perhaps it's floating in "dark matter water" (smirk) Mrob27 (talk) 19:23, 12 June 2023 (UTC)

- Below the surface of the water, sunlight has trouble penetrating. So clearly, the deepest parts of the oceans are dark matter. 162.158.2.183 02:00, 13 June 2023 (UTC)

Should a note be added emphasis this was published June 9th, not to be confused with the following June 16th when the Oceangate sub sets off? Maybe this talking point is enough? 172.70.178.54 18:45, 25 June 2023 (UTC)