1553: Public Key

| Public Key |

Title text: I guess I should be signing stuff, but I've never been sure what to sign. Maybe if I post my private key, I can crowdsource my decisions about what to sign. |

| |

This explanation may be incomplete or incorrect: first draft If you can address this issue, please edit the page! Thanks. |

Explanation

In Public-key cryptography, two keys are generated for a user. The public key can be used to encrypt messages, but not decrypt them. The private key is necessary for decryption, and as its name implies, is meant to be used solely by the user.

Since the public key is initially designated to be shared, anyone who has that key can send the user an encrypted message that only he or she can decrypt. Cueball has been following this rule, but he notices that it appears nobody has ever used his public key for anything. He contemplates sharing his private key, which he believes would generate more interest in him personally. However, he appears to overlook the fact that doing so would allow anyone to decrypt messages sent to him, thus defeating the entire purpose of encryption.

If Cueball initially released his private key instead of his public one, it would make no difference, since the importance is in keeping one key private - the keys themselves do not hold "private" or "public" roles until one is released and becomes the public key. However, since Cueball has already released his public key, releasing his private key would compromise the key pair. Even if he attempted to remove records of his public key, chances are that some sites would still have it somewhere.

The title text refers to another feature of Public-key cryptography: In addition to assuring that certain messages can only be read by a specific key owner, it can also assure that certain messages could only have been written by a specific key owner, by "signing" it using the private key. Anyone can read a signed message, but readers with the public key can then verify that the owner of the private key wrote (or at least signed) the message, rather than someone pretending to be the owner. If Cueball published his private key, then anybody could sign any message as him, effectively impersonating him and also defeating the purpose of encryption.

Crowdsourcing is the term used for delegating work or tasks to a largely volunteered and uncontrolled set of people on the Internet. It is similar in concept to outsourcing, in which work is delegated to an external source of labor, typically a company in a foreign country. Famous instances of crowdsourcing include reCAPTCHA (in which users both verify they are human and help digitize words and phrases in books that digitization software cannot understand) and a farm in the UK in which ordinary Internet users make decisions about how the farm is run. In Cueball's case, delegating decisions about his contracts and spending to the Internet is not likely to be a wise choice.

Randall previously ironically mentioned a public key in 370: Redwall.

Transcript

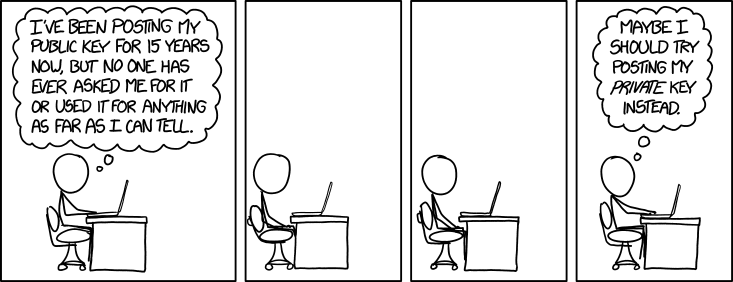

[In the first panel, Cueball is sitting in a chair and is using a laptop.]

Cueball: I've been posting my public key for 15 years now, but no one has ever asked me for it or used it for anything as far as I can tell.

[Two panels with Cueball thinking silently.]

Cueball: Maybe I should try posting my private key instead.

Discussion

I'm assuming he's referring to the GPG/PGP Key. Basically you have a key pair, one private that you use to sign/encrypt and one public, which can be used to verify your private key was used to sign. See Wikipedia for more information. If you posted your private key, anyone could sign as if they were you. I sign pretty much everything (not to mailing lists though), but don't think I've seen anyone else ever do so, even those I know have keys. See 1181: PGP for more. 198.41.235.35 04:59, 20 July 2015 (UTC)

- Don't believe everything certification authorities are telling you. X.509 SSL certificates works exactly same. Certificate is just a public key signed by certification authority. And yes, you can sign email with X.509 certificate. -- Hkmaly (talk) 09:54, 20 July 2015 (UTC)

This comic should be added to Category:Cryptography, but I'm not sure how to do that or whether I can do that. Nick818 (talk) 07:06, 20 July 2015 (UTC)

- Nick818—Someone did this today, but for your future reference, you just need to add [[Category:Cryptography]] to the page that needs to be categorized. It's helpful and customary to add the code to the bottom of the page. Cheers, jameslucas (" " / +) 10:21, 20 July 2015 (UTC)

This explanation completely misses the point that the PGP workflow is fundamentally flawed which has been stated by more than one expert, e.g. famously last year by Matthew Green, leading to demands to "let it die" and be replaced by something workable. --108.162.254.190 11:21, 20 July 2015 (UTC)

- The problem is, that there isn’t anything more “workable” at the moment. BTW: 7CD1E35FD2A3A158. --DaB. (talk) 11:27, 20 July 2015 (UTC)

- Well, I don't want to solve the problem of front-end cryptography here, and this site won't either. But the comic appeared in a climate of a quite general consensus and acceptance of the failure of PGP/GPG, and not technically but because of social and usability reasons. This explanation letting out that is quite comically in itself. --108.162.254.190 13:12, 20 July 2015 (UTC)

Remember Responsible Behavior? https://xkcd.com/364/ Xquestion (talk) 13:03, 20 July 2015 (UTC)

But did the author post his public key anywhere ? :v 141.101.104.166 17:29, 20 July 2015 (UTC)

Worth noting that posting his private key actually would be crowdsourcing his signing decisions, since anyone could do it. 108.162.221.102 04:57, 21 July 2015 (UTC)

-----BEGIN PGP SIGNED MESSAGE----- Hash: SHA1 FWIW, I use PGP. :) -----BEGIN PGP SIGNATURE----- Version: GnuPG v1 iEYEARECAAYFAlWuhWoACgkQHkr3KdXO/9A/ZACeM5Oho5XEDZnjo2q4yZBTqABo ET0Ani928heXg9aHmju0e0aK8JV7pvxH =CsEo -----END PGP SIGNATURE-----

— tbc (talk) 18:17, 21 July 2015 (UTC)

"the keys themselves do not hold "private" or "public" roles until one is released and becomes the public key" --- that might be true of some crypto-systems, but it is definite not' true of anything based on RSA, such as PGP/GPG. The prime factors (or exponents derived from them) are definitely the "private" part, and the composite product is definitely the "public" part. You cannot simply choose which part of the pair to make public. 108.162.238.181 19:54, 21 July 2015 (UTC)

"The prime factors (or exponents derived from them) are definitely the "private" part, and the composite product is definitely the "public" part". This is completely incorrect. In PGP (or rather, RSA keys used by PGP), both the public and private keys consist of just the modulus n (composite product) and one of the exponents d or e. However, the "public" exponent is typically chosen to be small and with few bits set, so that encryption/decryption using the public key is fast. The private key has to be big in order to keep the search space wide. So by switching around the public and private keys you end up with a public exponent that is a 600 digit number and a private exponent that is probably the number 65537. 198.41.243.252 09:16, 22 July 2015 (UTC)

- The public and private exponents are related by the p and q values. You chose one and then calculate the other. Normally you chose the public exponent and generate the private one. It's also common practice to store p and q with the private key for efficency reasons (see: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/RSA_%28cryptosystem%29#Using_the_Chinese_remainder_algorithm ). So 108.162.238.181's comment wasn't too far off the mark, the public key in a typical RSA system consists of the modulus and a well-known exponent, the private key in a typical RSA system consists of p,q and various values derived from them. You could build a RSA system with symmetry in the key pair so you can chose either key as the public one but noone does because it would be substantially more computationally intensive and would give little benefit. Plugwash (talk) 19:47, 23 July 2015 (UTC)

Is it possible everyone overthought this? It seems to me that it's partly a play on words. Why would people be interested in a "public" key which simply as a matter of the name seems like something that wouldn't be hidden in the first place? It would seem that people would be more interested in a "private" key, since it seems to be something you wouldn't be able to get. 173.245.50.149 18:53, 26 July 2015 (UTC)

- You're right in a general sense, but this wasn'the overthought. This is definitely about public/private key cryptography, and Randall has made comics about this before. His public key isn't interesting because no one wants to send secret messages to him; his private key would be very interesting because giving it out is a bad idea. 173.245.54.37 01:12, 11 February 2016 (UTC)