Difference between revisions of "2878: Supernova"

(→Explanation: Mixed up my edited tenses, whilst rearranging.) |

B for brain (talk | contribs) m (→Explanation) |

||

| Line 11: | Line 11: | ||

==Explanation== | ==Explanation== | ||

{{incomplete|Created by A CAGEY ASTRONOMER - Please change this comment when editing this page. Do NOT delete this tag too soon.}} | {{incomplete|Created by A CAGEY ASTRONOMER - Please change this comment when editing this page. Do NOT delete this tag too soon.}} | ||

| − | A {{w|supernova} occurs when a heavy star collapses when its original fuel runs out and it can no longer produce enough energy to fight its own gravity. The collapsing mass leads to a violent explosion, one of the most interesting events for astronomers to observe and one that can be used to glean information about the universe. | + | A {{w|supernova}} occurs when a heavy star collapses when its original fuel runs out and it can no longer produce enough energy to fight its own gravity. The collapsing mass leads to a violent explosion, one of the most interesting events for astronomers to observe and one that can be used to glean information about the universe. |

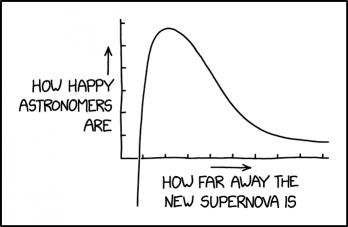

At first glance, this graph shape appears to show a '''light curve''', a common supernova graph constructed by plotting the '''brightness''' of a supernova as a function of '''time'''. Such a light curve graph looks somwhat like this, with negative values perhaps indicating a logarithmic scale (below zero indicates a linear brightness of less than the unit amount), to explain how that segment of the line reaches into the negative range, but not the astronomical "magnitude" (for which lower, and thus negative, values actually indicate ''increasing'' brightness). But it has been most often the case that an unremarkable star, possibly not even visible to the naked eye, has become notably bright over a short period of time before trailing off again to leave a stellar remnant and expanding cloud of ejecta. | At first glance, this graph shape appears to show a '''light curve''', a common supernova graph constructed by plotting the '''brightness''' of a supernova as a function of '''time'''. Such a light curve graph looks somwhat like this, with negative values perhaps indicating a logarithmic scale (below zero indicates a linear brightness of less than the unit amount), to explain how that segment of the line reaches into the negative range, but not the astronomical "magnitude" (for which lower, and thus negative, values actually indicate ''increasing'' brightness). But it has been most often the case that an unremarkable star, possibly not even visible to the naked eye, has become notably bright over a short period of time before trailing off again to leave a stellar remnant and expanding cloud of ejecta. | ||

Revision as of 19:35, 9 January 2024

| Supernova |

Title text: They're a little cagey about exactly where the crossover point lies relative to the likelihood of devastating effects on the planet. |

Explanation

| This explanation is incomplete: Created by A CAGEY ASTRONOMER - Please change this comment when editing this page. Do NOT delete this tag too soon. If you can address this issue, please edit the page! |

A supernova occurs when a heavy star collapses when its original fuel runs out and it can no longer produce enough energy to fight its own gravity. The collapsing mass leads to a violent explosion, one of the most interesting events for astronomers to observe and one that can be used to glean information about the universe.

At first glance, this graph shape appears to show a light curve, a common supernova graph constructed by plotting the brightness of a supernova as a function of time. Such a light curve graph looks somwhat like this, with negative values perhaps indicating a logarithmic scale (below zero indicates a linear brightness of less than the unit amount), to explain how that segment of the line reaches into the negative range, but not the astronomical "magnitude" (for which lower, and thus negative, values actually indicate increasing brightness). But it has been most often the case that an unremarkable star, possibly not even visible to the naked eye, has become notably bright over a short period of time before trailing off again to leave a stellar remnant and expanding cloud of ejecta.

However, this comic reimagines the light curve graph shape to show a graph that displays how happy astronomers would be when they discover a new supernova based on how far away it is from Earth. The further away one is, the less detail can be learned from it, and thus the less happy astronomers are. But a supernova closer than, say, 100 light years might be too close. Its radiation could destroy life on Earth, or at least significantly harm the biosphere. Astronomers (and many others) would be really unhappy if that happened,[citation needed] shown as sharply negative happiness (below the X axis) for a supernova that is too close.

Many astronomers watch and study the stars in the night sky, even the ones that don't change appreciably over human timescales, but observing and recording such a huge event would be interesting for many reasons. Even if not directly involved in the science, humans can observe some supernovae with the naked eye, especially if they occur within our own galaxy and are clearly visible from Earth. A potential supernova in the news lately is Betelgeuse, a red giant star that is the left shoulder in the constellation Orion. About 430 light years from the Sun, it has been pulsating, dimming and brightening over exceedingly short time scales compared to the tens of millions of years such a big star is expected to burn. Though it could yet easily go several thousand years before it goes supernova, it could also already have exploded and we are only waiting for the light from the event to reach Earth. Betelgeuse should be far enough away from Earth that the inevitable explosion would be safe enough for life on Earth (although some assessments are not so sure), but it will outshine all other stars in the night sky, possibly competing with the Moon, and could even be visible during daytime. This would be a dream come true for many astronomers and something obvious to others interested in the night sky. In the first Stargazing comic, 1644, the wish that it goes supernova (in Randall's lifetime) is clearly expressed.

Since this should be safe for us, and since it would be a spectacle not seen for hundreds of years here on Earth, this would make the astronomers very happy, not just from all they could learn, but also from just from all the increased interest in gazing at the sky with the 'new' star (and then seeing what happens to it next).

A distance exists where the astronomers would be the most happy, with anything nearer than that being less good (or very bad). As more distant phenomena only decrease the positive effects (and certainly do not increase the bad ones), the graph beyond the maximum happiness appears to show an asymptotic approach to less and less positive influence on the mood of the astronomers. There are thought to be about three supernovae occuring per century within our own galaxy (most stars of which are far further away from Betelgeuse), and many other nearby and far more distant galaxies within which a supernova explosion can be detected. These remain useful to see, and are often studied as intensively as possible, but have decreasing amounts of thrill to them and are harder to notice/record in the early stages of the explosion (or immediately before, to add even more understanding).

The title text expands upon the latter point of nearness, in that the astronomers themselves are not quite clear/unwilling to admit how close they would like a supernova to be. If it were close enough to severely impact the quality of human life, they would presumably not be happy, but they might actually be willing to accept some trouble for Earth life if they get to the see a supernova comparatively close by.[citation needed]

If the supernova were to instantly destroy Earth, or kill off all life on it, the astronomers may no longer be able to be happy or unhappy; this could be very much dependent upon what, if any, are the subsequent feelings of theologists/spiritualists/etc.

This is the second comic in a row that mentions exploding stars, after 2877: Fever, which like this comic is also a Charts comic.

Transcript

- [A graph is shown where the axes are labeled and arrows are pointing upward above the Y axis label and to the right above the X axis label. There is a single line on the graph that peaks close to the Y axis, where it reaches close to the top of the drawn part of the Y axis. Then the line approaches the X axis asymptotically towards the far right. But closer to the Y axis, the peak line goes almost vertically down, and continues far below the "bottom of the chart", outside of the boundary of the graph that was only supposed to be above the X axis.]

- Y axis: How happy astronomers are

- X axis: How far away the new supernova is

Discussion

It's all fun and games until the supernova is 93 million miles away Poxy6 (talk) 13:03, 8 January 2024 (UTC)

- Luckily there's only one star that close, and it's not big enough to become a supernova. "when our Sun runs out of hydrogen fuel, it will expand to become a red giant, puff off its outer layers, and then settle down as a compact white dwarf star" [1]. Of course, that will still destroy the Earth. Barmar (talk) 16:33, 8 January 2024 (UTC)

- "...there's only one star that close at the moment!". ;) Ok, so we haven't seen anything likely to swing by close (any time soon), never mind being in an explody frame of mind whilst doing so, but... :p 172.71.178.61 16:41, 8 January 2024 (UTC)

- Alpha Centauri is very nearly identical to our sun. It will also go red giant and then explode.Nitpicking (talk) 16:53, 8 January 2024 (UTC)

This seems to be a very early release. I had not expected to find a new comic already. Maybe Randall knows Betelgeuse goes Super Nova today... He can't wait - see 1644: Stargazing! Unless of course it is too close! (Betelgeuse should be a safe distance away and seems by far the closest Super Nova candidate, as least according to Astronomer Patrick Moore). --Kynde (talk) 13:07, 8 January 2024 (UTC) I added an explanation and transcript 172.70.43.108 13:09, 8 January 2024 (UTC)

I wonder if randall has played outer wilds 172.70.178.53 16:34, 8 January 2024 (UTC)

I recall other proximity chart comics about 'how close people are to things' such as proximity to cats. Maybe someone can find those and add them as references. Laser813 (talk) 16:40, 8 January 2024 (UTC)

I'm feeling lazy and not feeling like verifying this, but I think the graph is also representative of the light curve we expect to see during a supernova. The stars brightness reaches a peak very quickly, then more gradually diminishes. Galeindfal (talk) 18:04, 8 January 2024 (UTC)

- Exactly, I thought this was the joke: The graph under the title "Supernova" looks just like a Type Ia supernova light curve, but then it turns out to be about enthusiastic astronomers. It seems supernovae aren't only helpful in establishing a distance scale to astronomers, but also to behavioural scientists who study astronomers. Transgalactic (talk) 20:55, 8 January 2024 (UTC)

- even a superficial search by a behavioural scientist (who also handle statistics :) makes this aspect obvious. Absolutely worth to integrate it into description! https://www.ecosia.org/images?addon=opensearch&_sp=32592cb2-9564-46eb-9b5c-5ae955333b74&q=supernova+graph --LaVe (talk) 00:57, 9 January 2024 (UTC)

Why the fuck aren’t the units and magnitude of the axes labled? I had to use my brain. 172.70.207.89 05:28, 9 January 2024 (UTC)

Surely there should be some dotted sections, particularly the gap between the edge of the Milky Way and Andromeda, then the next nearest galaxy (where there are few stars)? RIIW - Ponder it (talk) 08:33, 9 January 2024 (UTC)

Anyone know of a recent event that could have inspired this comic? Betelgeuse is mentioned in the explanation but has there been any newsworthy supernovae in the past week? Alcatraz ii (talk) 05:49, 9 January 2024 (UTC)

- Maybe this? 172.70.210.40 12:31, 9 January 2024 (UTC)

- Oh yes! Transgalactic (talk) 21:43, 9 January 2024 (UTC)

isn't the chart missing an uptick to the right? wouldn't the appearance of a supernova at, say, 13.6bn light years away make astronomers extremely happy? --172.70.91.211 15:40, 9 January 2024 (UTC)

The shape of the graph is very similar to 815: Mu guess who (if you want to | what i have done) 17:49, 9 January 2024 (UTC)

- That one's decline is much flatter. Transgalactic (talk) 21:43, 9 January 2024 (UTC)

No. It could not have already exploded. This indicates a lack of understanding of relativity. The more accurate statement would be that from our perspective, Betelgeuse hasn't exploded yet, and from the perspective of Betelgeuse, Earth is as it was 700 years ago (local to earth), and from the midway point between Earth and Betelgeuse, Earth is as it was 350 years ago (local to earth) and Betelgeuse is as it was 350 years ago (local to Betelgeuse). Simultaneity changes with the perspective of the observer. 172.69.22.51 (talk) 18:44, 9 January 2024 (please sign your comments with ~~~~)

- It is, however, possibly at the stage of "though we do not yet know it, we are to experience the signs of it having happened prior our own current time" (as in broadcasting "have you exploded yet?" would not have been answerable before it actually does, even if we somehow managed to do so several hundred years ago). But rewrite it as you see fit. I can see why the author of the current version decided not to go into that, and why you might be put off from trying to give the "more correct" version an airing through your own edit... 172.70.91.11 19:02, 9 January 2024 (UTC)

- It would be more of an edit than a re-write, as the statement should simply be struck. It is incorrect to say that what we see 300 LY away occurred 300 years ago. We simply have a view of spacetime based on our relative position that, should that position change with respect to Earth and Betelgeuse, would mean different simultaneity (not just from a light perception perspective, but when it comes to causality in general). If it helps, then I'll go in and remove the errant phrase.

I just redacted much of the explanation because it was riddled with repetitions, errors and scientific imprecisions. (I didn't elaborate on the relativity issue, though, just added "locally" to that sentence.) I Hope you appreciate the result. Transgalactic (talk) 21:43, 9 January 2024 (UTC)