1491: Stories of the Past and Future

| Stories of the Past and Future |

Title text: Little-known fact: The 'Dawn of Man' opening sequence in 2001 cuts away seconds before the Flintstones theme becomes recognizable. |

- A larger version of this image can be found here.

Explanation[edit]

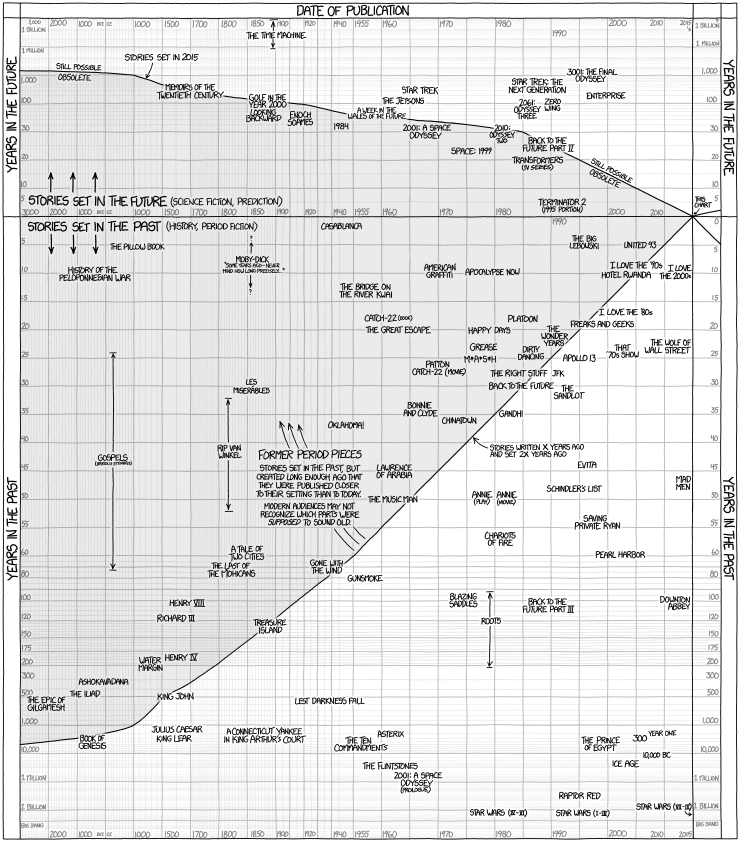

It's long been common for narrative works to be set in the past, and this tendency goes back to ancient mythology. The opposite approach, setting a work in a speculative future, has been less common prior to modern times. The oldest example Randall presents is from 1733, but it didn't really become a trend until well into the 19th century, and didn't become really common until the 20th century.

For works set in the future, particularly in the near future, there's a real possibility that audiences will still read or watch it past the date in which is was set, allowing them to compare the real world of this era to the one the author projected. This doesn't make the work less valuable, necessarily, but it does make the limits of such speculation painfully obvious, and tends to make the future presented there look dated and quaint. Randall labels these futuristic works as "obsolete".

For works set in the past, there's an opposite and somewhat more subtle effect. Once the work itself is old enough, audiences tend to forget that they were intended as historical fiction in the first place. If an old work is set in the past, it's often assumed that they were set in their own time, not in the still more distant past. That impacts how we experience the work, because we tend to assume that it's a faithful representation of its own time, not a later interpretation that was intended to be old (and possibly nostalgic) even in its own time.

On top of this, in a similar situation to the failed attempt at futurology, for future-facing works of fiction, even a conscientiously faithful 'historic' film can age badly. Later understanding of previously hazy historical situations can be developed between the time of the fictional work being authored and your experience of it.

To demonstrate those impacts, this chart sorts various works by the year they were created, graphed against how far in the past or future they were originally set. Lines on the chart are added to separate when each work ceases to work as either a prediction or as a period piece. For future works, the cut-off is obvious: if it was set in a year prior to the current year, we know that the predictions are obsolete (and can easily determine how accurate or inaccurate that future is). Hence, at the time the chart was written (in 2015), works like 1984 and 2001: A Space Odyssey are obsolete, while works like Star Trek, which take place in a more distant future, are still theoretically possible. (Back to the Future Part II is deliberately right on the line, as it was set in 2015).

For the past works, Randall sets the cut-off as when the work itself is older than the events in question were when it was first written/made. Hence, modern audiences are unlikely to realize that the Epic of Gilgamesh was intended to sound ancient, even when it was new, or that novels like Les Miserables were intended as historical fiction, or even that films like Chinatown or shows like Happy Days were intended as period pieces when they were made. To modern audiences, we just see an old work set in an old time, and tend to assume that the two periods were the same.

The setup of the chart points to the reality that, in process of time, more and more works will cross those lines. Future audiences will likely assume that films like Apollo 13 and Schindler's List were made around the time of the events in question. And modern science fiction works, if they're still remembered in the future, will become just as obsolete as past works. And Randall even indicates "this chart" on the chart, apparently acknowledging that it will become dated as time goes by.

The title text jokes that 2001 cuts from prehistoria to the future before The Flintstones theme can become recognizable. This references the fact that, despite being primarily set in what was then the future, the film opens in the ancient past, thus appearing in both parts of the graph, with one part being very close to The Flintstones. This plays on the fact that one of these was a very serious work and the other a playful animated show that was intended as family comedy. Also, the prehistoric part ends with an hominid screaming, in a way that could transition into the horns of The Flintstones opening.

How to read the graph[edit]

- X-axis: Date of publication.

- Y-axis, "Years in the future": Number of years the story's events take place, after the story's publication.

- Y-axis, "Years in the past": Number of years the story's events take place, before the story's publication.

- For example, "Water Margin" was published in the 14th century (x ~= 1300) and relates events from the 12th century, about 200 years before its publication (y ~= 200 in the past).

- Another example: The film The Bridge on the River Kwai was released in 1957 and it was set around 14 years before (~1942-43).

- Grey area in the "Years in the future" part: Stories set in the future (relative to their publication date), for which the date of the events in the story is already in the past (relative to the publication date of the comic). The white and gray areas in this part of the graph are defined as "still possible" and "obsolete", respectively. The gray area (obsolete) will expand over time, assuming more works aren't added in the future: predictions from science fiction or futuristic work that are not confirmed by reality are doomed to be obsolete.

- Grey area in the "Years in the past" part: Stories set in the past (relative to their publication date) but published closer to their setting than to today. The warning "Modern audiences may not recognize which part were supposed to sound old" is a recurrent theme in the author's work, being already formulated in Period Speech comic. The white area seems to be the region where modern readers will be able to distinguish the past setting of a work from the age of the work itself. This gray area will grow over time (again assuming new works set in the past are not added) with more and more works being indistinguishable as works set in the past.

Taking the "years in the past" on the y-axis to be read as negatives like in most graphs one can write

- Dates on the lower line satisfy the equation y = x-2015. Corresponding works were published in the year x = 2015+y and are set in the year x+y = 2015+2y.

- Dates on the upper line satisfy the equation y = 2015-x. Corresponding works were published in the year x = 2015-y and are set in the year x+y = 2015.

Thus it's clear that the definitions of the lines are consistent with each other as they follow similar but inverted functions. The graph uses variable logarithmic scales, adjusting the scale in various regions to the temporal density of works being plotted. If the scale were linear, the graph would in fact represent a (bidimensional) Minkowski diagram, which depicts the moving cones of past and future in spacetime as one's present advances in time.

Works listed[edit]

Differences listed in bright red are "former period pieces." Differences listed in dark red are other works set in the past. Differences listed in bright green are "obsolete" works set in the future. Differences listed in dark green are other works set in the future.

Asterisks (*) after a year of publication denote that it applies to the first installment in a series that spanned more than one year.

You can sort by a specific column in this table by clicking on its header.

| Publication | Description | Year written | Year difference | Year set in | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Epic of Gilgamesh | ancient Mesopotamian epic poem | ~2100 BCE | ~500 | ~2600 BCE | Enmebaragesi, a historically attested Epic of Gilgamesh character, is thought to have lived around 2600 BCE |

| The Iliad | epic written by Greek poet Homer | 700s BCE | ~500 | 1260–1240 BCE | |

| Book of Genesis | first book of the Bible, describing the creation of the world | 500s–400s BCE | ~3200 | 3761 BCE | The Anno Mundi epoch, the product of scriptural calculations by Maimonides, places the Genesis date of the creation of the world at October 7, 3761 BCE in the proleptic Julian calendar |

| History of the Peloponnesian War | history written by Thucydides | ~400 BCE | ~10 | 431–411 BCE | |

| Gospels | collection of literary works detailing the life of Jesus of Nazareth | ~65–110 CE | 25–75 | 7–2 BCE – 30–33 CE | Setting dates are those of Jesus' estimated lifetime. Writing dates are as follows: Mark 65–73 CE; Matthew 70–100 CE; Luke 80–100 CE; John 90–110 CE. Randall's difference calculation seems to be based on the date of Jesus' death, as the majority of the Gospels' events takes place during the three years prior to Jesus's death. |

| Ashokavadana | narrative of the life of Ashoka the Great | 100s CE | ~400 | 304–232 BCE | |

| The Pillow Book | book written by Sei Shōnagon | 1002 | 6 | 996 | |

| Water Margin | novel by Shi Nai'an | late 1300s | ~150 | early 1100s | |

| Richard III | play by William Shakespeare | 1597 | 112–119 | 1478–1485 | |

| Henry IV | plays by William Shakespeare | 1598* | 185–196 | 1402–1413 | |

| King Lear | play by William Shakespeare | 1608 | 2400 | 700s BCE | |

| King John | play by William Shakespeare | 1623 | ~400 | ~1200–1216 | |

| Henry VIII | play by William Shakespeare | 1623 | 90–102 | 1521–1533 | |

| Julius Caesar | play by William Shakespeare | 1623 | 1667–1670 | 45–42 BCE | |

| Memoirs of the Twentieth Century | book written by Samuel Madden | 1733 | 264 | 1997 | |

| Rip Van Winkel [sic] | short story by Washington Irving | 1819 | 32–52 | 1767–1787 | It's not clear why Randall has chosen 1787 as the year that Rip Van Winkle awakes. |

| The Last of the Mohicans | novel by James Cooper | 1826 | 69 | 1757 | |

| Moby-Dick | novel by Herman Melville | 1851 | 5+ | before 1846 | Inspired by events occurring in 1820, the late 1830s, and the early 1840s |

| A Tale of Two Cities | book by Charles Dickens | 1859 | 84 | 1775 | |

| Les Miserábles [sic] | novel by Victor Hugo | 1862 | 47 | 1815–1832 | |

| Treasure Island | novel by Robert Louis Stevenson | 1883 | ~120 | ~1760 | |

| Looking Backward | novel written by Edward Bellamy | 1888 | 112 | 2000 | |

| A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court | novel by Mark Twain | 1889 | 1361 | 528 | |

| Golf in the Year 2000 | novel written by J. McCullough | 1892 | 108 | 2000 | |

| The Time Machine | novel written by H.G. Wells | 1895 | 800,000– 1 billion |

802,701– 1 billion |

Note that Randall has included only part of the book; which includes scenes all the way from the time of writing to the death of the last life on Earth. The novel itself identifies the latest part as being "more than thirty million years" in the future, based on the theories of the Sun's lifespan at the time. |

| Enoch Soames | short story by Max Beerbohm | 1916 | 81 | 1997 | Soames was transported from 1897 to 1997 and back. |

| Gone With The Wind | novel by Margaret Mitchel | 1936 | 75 | 1861 | |

| Lest Darkness Fall | alternate history SF novel by L. Sprague de Camp | 1939 | 1404 | 535 | |

| Casablanca | film directed by Michael Curtiz | 1942 | <1 | 1941 | The film was released 26 November 1942 and is set in early December 1941. |

| Oklahoma! | Broadway musical | 1943 | 37 | 1906 | |

| 1984 | novel written by George Orwell | 1949 | 35 | 1984 | |

| The Bridge on the River Kwai | film by David Lean | 1952 | ~10 | 1942–1943 | |

| Gunsmoke | American radio and television series | 1952* | ~75 | 1870s | 1952 is when the radio series started. The TV series didn't start until 1955. |

| The Ten Commandments | film by Cecil B. DeMille | 1956 | ~3000 | ~1446 BCE | The full timespan is supposedly 80 years (40 before Moses is exiled, then 40 in exile). |

| The Music Man | Broadway musical | 1957 | 45 | 1912 | |

| A Week in the Wales of the Future | novel written by Islwyn Ffowc Elis | 1957 | 76 | 2033 | |

| Asterix | French comic by Goscinny and Uderzo | 1959* | 2009 | 50 BCE | |

| The Flintstones | TV series produced by Hanna-Barbera | 1960* | ~2.5 million | Stone Age | |

| Catch-22 (Book) | novel by Joseph Heller | 1961 | ~17 | 1942–44 | |

| The Jetsons | TV series produced by Hanna-Barbera | 1962* | 100 | ~2062 | |

| Lawrence of Arabia | film by David Lean | 1962 | ~44 | 1916–1918 | |

| The Great Escape | film by John Sturges | 1963 | 20 | 1943–1944 | |

| Star Trek (TOS) | TV series created by Gene Roddenberry | 1966* | 298 | 2264 | |

| Bonnie and Clyde | film by Arthur Penn | 1967 | ~33 | 1932–1934 | |

| 2001: A Space Odyssey | novel written by Arthur C. Clarke | 1968 | 33 | 2001 | |

| 2001: A Space Odyssey (prologue) | prologue to novel written by Arthur C. Clarke | 1968 | 3 million | 3 million BCE | 4 million years BCE in the movie |

| Catch-22 (Movie) | film by Mike Nichols | 1970 | ~26 | 1942–1944 | |

| M*A*S*H | film by Robert Altman | 1970 | 19 | 1951 | |

| Patton | film by Franklin J. Schaffner | 1970 | ~25 | 1943–1945 | |

| American Graffiti | film by George Lucas | 1973 | 11 | 1962 | |

| Blazing Saddles | film by Mel Brooks | 1974 | 100 | 1874 | |

| Chinatown | film by Roman Polanski | 1974 | 37 | 1937 | |

| Happy Days | TV series | 1974* | 19–29 | 1955–1965 | |

| Space: 1999 | TV series created by Gerry and Sylvia Anderson | 1975* | 24 | 1999 | |

| Annie (play) | Broadway musical | 1977 | 44 | 1933 | |

| Roots | TV series, adapted from eponymous novel | 1977 | 90–227 | 1750–1882 | |

| Star Wars (IV – VI) | original film trilogy | 1977* | 1 billion | "A long time ago" | It's not clear why Randall has chosen 1 billion years here. Wookieepedia puts the age of the Star Wars galaxy at ~13 billion years, and our Universe is only 13.8 billion years old, and the oldest known galaxy took 380 million years to form... So it would seem Star Wars should be no farther than 400 million years in the past, give or take. |

| Grease | film by Randall Kleiser | 1978 | 20 | 1958 | |

| Apocalypse Now | film by Francis Ford Coppola | 1979 | 10 | 1969 | |

| Chariots of Fire | film by Hugh Hudson | 1981 | 57 | 1924 | |

| 2010: Odyssey Two | novel written by Arthur C. Clarke | 1982 | 28 | 2010 | |

| Annie (movie) | film adaptation of the above by John Huston | 1982 | 49 | 1933 | |

| Gandhi | film by Richard Attenborough | 1982 | ~34 | 1893–1948 | |

| The Right Stuff | film by Philip Kaufman | 1983 | ~20 | 1947–63 | |

| Transformers (TV Series) | TV series | 1984* | ~20 | ~2004 | Only seasons 3 and 4 are set in the year 2005 onwards. Seasons 1 and 2 were set in 1984-85. |

| Back to the Future | film by Robert Zemeckis | 1985 | 30 | 1955 | |

| Platoon | film by Oliver Stone | 1986 | 21 | 1967 | |

| Dirty Dancing | film by Emile Ardolino | 1987 | 24 | 1963 | |

| Star Trek: The Next Generation | TV series created by Gene Roddenberry | 1987* | 377 | 2364 | |

| 2061: Odyssey Three | novel written by Arthur C. Clarke | 1987 | 74 | 2061 | |

| The Wonder Years | TV series | 1988* | 20–25 | 1968–1973 | |

| Back to the Future Part II | film directed by Robert Zemeckis | 1989 | 26 | 2015 | Only the first part of the movie is set in 2015; later the setting moves to an alternate 1985 and a revisit of 1955. |

| Zero Wing | arcade/computer game | 1989 | 112 | 2101 | Previously referenced in 887: Future Timeline |

| Back to the Future Part III | film by Robert Zemeckis | 1990 | 105 | 1885 | |

| JFK | film by Oliver Stone | 1991 | ~22 | 1963–1969 | |

| Terminator 2 (1995 Portion) | film directed by James Cameron | 1991 | 4 | 1995 | |

| The Sandlot | film by David Mickey Evans | 1993 | 31 | 1962 | |

| Schindler's List | film by Steven Spielberg | 1993 | ~50 | 1939–1945 | |

| Apollo 13 | film by Ron Howard | 1995 | 25 | 1970 | |

| Raptor Red | novel by Robert Bakker | 1995 | ~65 million | Cretaceous Period | |

| Evita | film by Alan Parker | 1996 | 44 | 1952 | |

| 3001: The Final Odyssey | novel written by Arthur C. Clarke | 1997 | 1004 | 3001 | |

| The Big Lebowski | film by the Coen Brothers | 1998 | 7 | 1991 | |

| The Prince of Egypt | animated film by DreamWorks | 1998 | 3400 | ~1446 BCE | Despite the same plot of The Ten Commandments, it covers only about 30 years given its Moses is much younger. |

| Saving Private Ryan | film by Steven Spielberg | 1998 | 54 | 1944 | |

| That '70s Show | TV series | 1998* | ~22 | 1976–1979 | |

| Freaks and Geeks | TV series | 1999* | 19 | 1980–1981 | |

| Star Wars (I – III) | prequel film trilogy | 1999* | 1 billion | "A long time ago" | See note at episodes IV–VI |

| Pearl Harbor | film by Michael Bay | 2001 | 60 | 1941 | |

| Enterprise | TV series | 2001* | 150 | 2151 | |

| I Love the '80s | TV miniseries by VH1 | 2002 | 13–22 | 1980–1989 | |

| Ice Age | animated films by Blue Sky Studios | 2002* | ~12,000 | Paleolithic-Mesolithic | |

| Hotel Rwanda | film directed by Terry George | 2004 | 10 | 1994 | |

| I Love the '90s | TV miniseries on VH1 | 2004 | 5–14 | 1990–1999 | |

| United 93 | film directed by Paul Greengrass | 2006 | 5 | 2001 | |

| 300 | film by Zack Snyder | 2007 | 2487 | 480 BCE | |

| Mad Men | TV series | 2007* | ~47 | 1960–1970 | |

| 10,000 BC | film by Roland Emmerich | 2008 | 12,007 | 10,000 BCE | |

| Year One | film by Harold Ramis | 2009 | 2008 | 1 CE | The movie title is not intended to refer to 1 CE, as it is clearly set well before that; it is difficult to determine the film's actual year as it depicts Cain and Abel (c. 4000 BCE) existing simultaneously with Abraham, Sodom and Gomorrah (c. 2000 BCE). |

| Downton Abbey | TV series | 2010* | ~90 | 1912–1923 | |

| The Wolf of Wall Street | film by Martin Scorsese | 2013 | ~18 | 1987–1995 | |

| I Love the 2000s | TV miniseries on VH1 | 2014 | 14 | 2000 | |

| Star Wars (VII – IX) | sequel film trilogy | 2015* | 1 billion | "A long time ago" | See note at episodes IV–VI |

| This chart | xkcd comic | 2015-02-25 | 0.000 | 2015-02-25 | Self-referential |

Errors[edit]

Dates[edit]

- Star Trek: The Next Generation is vertically positioned at about 500 years in the future, slightly too high for its actual date. This may be to allow room for other nearby labels.

- The Gospels are horizontally positioned at about the year 250 CE, when they should be positioned slightly further to the left, near the 100 CE line. (While there is debate on their date of authorship, the range of "years in the past" indicated on the graph would require authorship between roughly 50 and 100 CE.)

- Lest Darkness Fall takes place about 1400 years in the past, in the year 535. Its placement on the graph indicates it takes place about 535 years in the past, in the year 1400.

Spelling[edit]

- Author Washington Irving titled his work Rip Van Winkle, not Rip van Winkel as Randall spells it. That said, van Winkel may be a more historically authentic spelling.

- Les Misérables has been misspelled Les Miserábles (note that French doesn't use the character "á").

Transcript[edit]

| This is one of 42 incomplete transcripts. Please help by editing it! |

- Date of publication

- [A logarithmic scale running horizontally, from 3000 BCE to past 2015 CE.]

- Years in the future

- [A logarithmic scale running vertically, from 1 billion down to 0.]

- Stories set in the future (science fiction, prediction)

- Stories set in 2015

- [A line divides this region into two. The upper side is labelled "still possible"; the lower side is labelled "obsolete".]

- [From left to right.]

- Memoirs of the Twentieth Century [1700, 265 years in the future]

- Looking Backward [1888, 112 years in the future]

- Golf in the Year 2000 [1892, 108 years in the future]

- The Time Machine [1895, 800 thousand to 30 million years in the future]

- Enoch Soames [1916, circa 60 years in the future]

- 1984 [1949, 35 years in the future]

- A Week in the Wales of the Future [1957, 76 years in the future]

- The Jetsons [1962-63, 100 years in the future]

- Star Trek [1966-69, 300 years in the future]

- 2001: A Space Odyssey [1968, 33 years in the future]

- Space: 1999 [1975-77, 24 years in the future]

- 2010: Odyssey Two [1982, 28 years in the future]

- Transformers (TV series) [1984-87, 20 years in the future]

- 2061: Odyssey Three [1987, 74 years in the future]

- Star Trek: The Next Generation [1987-94, circa 500 years in the future]

- Back to the Future Part II [1989, 26 years in the future]

- Zero Wing [1989, 112 years in the future]

- Terminator 2 (1995 portion) [1991, 4 years in the future]

- 3001: The Final Odyssey [1997, 1004 years in the future]

- Enterprise [2001-2005, 150 years in the future]

- This chart [2015, 0 years in the future]

- Years in the past

- [A logarithmic scale running vertically, from 0 down past 1 billion to "Big Bang"]

- Stories set in the past (History, Period Fiction)

- Stories written X years ago and set 2X years ago

- [A line divides this region into two. The upper side is labelled as follows.]

- Former period pieces

- Stories set in the past, but

created long enough ago that

they were published closer

to their setting than to today. - Modern audiences may not

recognize which parts were

supposed to sound old.

- [From left to right.]

- The Epic of Gilgamesh [circa 2100 BCE, 600 years in the past]

- The Iliad [circa 800 BCE, 450 years in the past]

- History of the Peloponnesian War [circa 390 BCE, 10 years in the past]

- Book of Genesis [circa 500 BCE, 4000 years in the past]

- Ashokavadana [circa 100 BCE, 300 years in the past]

- Gospels (various estimates) [circa 250 CE, 24 to 75 years in the past]

- The Pillow Book [1000 CE, 5 years in the past]

- Water Margin [circa 1300, 195 years in the past]

- Richard III [circa 1590, 115 years in the past]

- Julius Caesar [1599, 1650 years in the past]

- King John [circa 1600, 500 years in the past]

- Henry IV [circa 1600, 190 years in the past]

- King Lear [circa 1606, 3000 years in the past]

- Henry VIII [circa 1612, 105 years in the past]

- The Last of the Mohicans [1826, 69 years in the past]

- Rip Van Winkel [1819, 31-51 years in the past]

- A Tale of Two Cities [1859, 60 years in the past]

- Moby-Dick [1851, anywhere from 4 to 14 years ago]

- "Some years ago--never mind how long precisely..."

- Les Miserábles [1862, 30 years in the past]

- Treasure Island [1883, 130 years in the past]

- A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court [1889, 2000 years in the past]

- Gone with the Wind [1936, 70 years in the past]

- Lest Darkness Fall [1939, 550 years in the past]

- Casablanca [1942, 1 year in the past]

- Oklahoma! [1943, 37 years in the past]

- The Ten Commandments [1956, 1400 years in the past]

- The Bridge on the River Kwai [1957, 13 years in the past]

- Gunsmoke [1952-61, 80 years in the past]

- The Flintstones [1960-66, 100,000 years in the past]

- Catch-22 (book) [1961, 18 years in the past]

- The Great Escape [1963, 20 years in the past]

- Asterix

- Lawrence of Arabia

- The Music Man

- Bonnie and Clyde

- 2001: A Space Odyssey (prologue)

- American Graffiti

- Patton

- Catch-22 (movie) [1970, 27 years in the past]

- Chinatown

- Blazing Saddles

- Apocalypse Now

- Happy Days

- Grease

- M*A*S*H

- Annie (play)

- Roots

- Chariots of Fire

- Star Wars (IV-VI)

- Annie (movie)

- The Right Stuff

- Back to the Future

- Gandhi

- Platoon

- Dirty Dancing

- Back to the Future Part III

- The Wonder Years

- JFK

- The Sandlot

- Schindler's List

- Raptor Red

- Apollo 13

- Star Wars (I-III)

- The Big Lebowski

- Evita

- Saving Private Ryan

- The Prince of Egypt

- Freaks and Geeks

- Hotel Rwanda

- I Love the '80s

- That '70s Show

- Pearl Harbor

- Ice Age

- I Love the '90s

- United 93

- 300

- 10,000 BC

- Year One

- The Wolf of Wall Street

- I Love the 2000s

- Mad Men

- Downton Abbey

- Star Wars (VII-IX)

Trivia[edit]

- Later after the initial release of this comic Randall added a link to this page. It is viewable in the HTML-source or here: https://xkcd.com/1491/info.0.json. The text is: "this is a massive fucking graph beyond the limits of normal transcription. you can find a full listing of data points at http:\n\nwww.explainxkcd.com\nwiki\nindex.php\n1491".

Discussion

http://xkcd.com/1491/large/ will take you to the large version, which the comic currently doesn't have a link to. I expect that will be fixed shortly. 108.162.210.177 05:30, 25 February 2015 (UTC)

- I just realized he has a text link for it in the top banner. I'd delete my comment, but that's rude on a wiki. Whatever. 108.162.210.177 05:35, 25 February 2015 (UTC)

The bottom diagonal seems to be mislabelled? Shouldn't it be "Stories written X years and set X years ago" instead of "set 2X years ago"? --108.162.250.175 05:38, 25 February 2015 (UTC)

- It is correct, if you see both relative from now. The middle line is written X years ago and set X years ago and thus contemporary. Sebastian --108.162.231.68 06:46, 25 February 2015 (UTC)

I'm not sure where to open bug tickets, but Lest Darkness Fall actually takes place ~1500 years ago, not ~500. 141.101.80.121 06:35, 25 February 2015 (UTC)

- I'll second that -- Brettpeirce (talk) 12:36, 25 February 2015 (UTC)

Kind of reminds of a Minkowski diagram. Sebastian --108.162.231.68 06:50, 25 February 2015 (UTC)

More and more science fiction works wander into the category obsolete science fiction, and more and more historical works are not recognisable as such by the average viewer as the movies have been filmed such a long time ago anyway. Sebastian --108.162.231.68 06:55, 25 February 2015 (UTC)

There seems to be a mistake with the large diagonal line. It says "Stories written X years ago and set 2X years ago." It should say, "... and set X years ago." Am I missing something here? Effy (talk) 09:35, 25 February 2015 (UTC)

- Nevermind, I see now that the y-axis is date relative to publication, not absolute dates relative to today. My bad. Effy (talk) 09:37, 25 February 2015 (UTC)

I may have missed it, but can't see Paris in the Twentieth Century, written in 1863, about 1960, but only published in 1994. Which would have been an interesting addition. 141.101.98.192 10:13, 25 February 2015 (UTC)

- In fact, I'm thinking it could have been represented as a (dotted?) diagonal arrowed line between "1960 in 1863"/future-trending and "1960 in 1994"/past-trending points. But never mind. 141.101.98.192 10:38, 25 February 2015 (UTC)

... this is why experienced sci-fi writers don't date their stories. On the other hand, many sci-fi became obviously obsolete even without the date. -- Hkmaly (talk) 11:00, 25 February 2015 (UTC)

- I have experience with this. Back in 1995 I advised a prospective author-friend (prospective author; already and still a friend, surprisingly) on the latest computing matters to help a plot device in a "five minutes into the future" story. Even two years later, it sounded so dated and... naff. ('Luckily', it didn't sell too well anyway (bad choice of publishers), so my failure-as-futurologist - uncredited as it also fortunately was - wasn't so wildly known.) 141.101.98.192 13:04, 25 February 2015 (UTC)

I've been trying and trying to figure out what the heck his point might be, as IMO there usually seems to be some point he's trying to make or way he's trying to be clever, beyond the interesting nature of the observation - and I think I might have seen one (though there is probably something else) - anyone notice that the area under the "Stories set in 2015" line is awfully bare? at least compared to the areas on either side of the 'x / 2x' line. that could simply be his particular selection of works(?) anyone have some ideas of things that might deserve to go in there that were not included? -- Brettpeirce (talk) 12:45, 25 February 2015 (UTC)

- I think the point here is that there are a lot of books one hasn't read yet. I, for one, sought out Memoirs of the Twentieth Century and The Pillow Book after reading this strip. --Koveras (talk) 13:30, 25 February 2015 (UTC)

- He has done stuff like that before, right? Putting the age of some books and movies into perspective, to make the reader feel old. --173.245.53.151 15:16, 25 February 2015 (UTC)

- maybe he just wants to see what the people who transcripe it will come up with.108.162.250.173 12:31, 26 February 2015 (UTC)

As for writing a transcript or explanation, concerning order, I would think it would make some sense to flatten it on one axis (probably the y-axis, starting from Star Wars?) or if it is practical enough, the best might be some sort of "radial"(?) axis (is that a thing?), where the axis would be anchored at "this chart", and swing like a radar beam around from the bottom (Downton Abbey, Mad Men, and Star Wars, up through the 'x / 2x' line, through the 'contemporary' line and then the 'set in 2015' line, to finish with '3001', possibly making a small attempt to keep related works (like Star Wars) together in the listing. Any comments? -- Brettpeirce (talk) 12:55, 25 February 2015 (UTC)

- Whatever the fixation, I started work on something, but other people will get there before me. So here's my ideas. Five columns: "Story (and format description/author?)", "First Published/Premiered", "Date offset(s)", "Featured date(s)" and "Notes", with sorting on each potentially numerical one (although ranges/freetext/vagueness may play havoc with such sorting, by past experience).

- I already have a complete list of listed titles (in case anyone needs it), though maybe not error-free and not yet been ordered other than by "input order".

...excised by original author...

- (Do cut that out of this Talk Page when no longer necessary!)

- What I've so far put together (but not yet checked my link formats or WikiTabled) is...

...excised by original author...

- ...but I'm probably duplicating someone else's efforts so by the time I get back to it you'll have a complete and better version online. FYI if you're determined to build on this while I'm absent, however. 141.101.98.192 14:22, 25 February 2015 (UTC)

This appears to be a log-log graph, but with abrupt changes in scale along one axis yielding cusps in the "still possible / obsolete" line. Is there a name for that? -- 108.162.210.169 14:29, 25 February 2015 (UTC)

- Hello, me again. I'd also played with a 'transcript description' part. Use (or don't, or correct and then use) what I was writing, if you want. I'm taking the liberty of deleting my prior inserts while I'm here, to avoid the clutter.

X-axis represents "date of publication" of a work and is irregularly split into 1000s (3000BCE to 1000CE) and then decreasing periods of time until 1955, at which point it becomes every five years up to the present day (2015) and one devision of possibly five years into the future (the upcoming "third Star Wars Trilogy" is indicated by an arrow as lying on-or-beyond 'now', with Episode 7 itself due out not long after the comic date). Y-axis represents "years ahead/behind publication date in which a story is set" with the 'zero axis' being "set at the time of publication. "Years in the future" spreads above, by decades until "30 years" then in a metalogarithmic manner through various orders of ten to top-out at 1 billion years. The "Years in the past" scale, below this, extends by five years down to 60 years and then similarly quickly speeds through to 1 billion years in the past, and the time of the Big Bang as lowest limit. Above the 'here and now', a region is shaded within a line to represent the border between future settings that should have happened by this date, and below we find a similar shading/line that represents set twice as long ago as was written. Both lines continue into "2015+" territory in a manner similar to a "light cone".

- ...ok? 141.101.98.192 15:43, 25 February 2015 (UTC)

I created a basic table using 141.101.98.192's data - bits corrected. Jarod997 (talk) 14:46, 25 February 2015 (UTC)

I'm in the process of writing a transcript myself. Mine is not formatted as a table; I am under the impression that this is the preferred approach to transcripts on this site. However, the existing table would be perfect in another section, where we can give more detail than a true transcript can/should provide (e.g. "this is a book written by X, here's the wikilink", "this is an error, it should be X", etc.) -- Peregrine (talk) 14:55, 25 February 2015 (UTC)

- Meh, I created the table as a starting point. If people want to use it and add to it, great. If something better is created, that's fine too. :) Jarod997 (talk) 15:12, 25 February 2015 (UTC)

- I've moved the table to its own section and put in my more minimalistic, list-style transcript (based on what I found in other "large drawing" articles. I have only included dates in the transcript as an indication of the coordinates at which each item is located (and I found several that seem misplaced vertically, perhaps to accommodate other labels, e.g. Next Generation). Also, it isn't finished; everything's listed, in (more or less) the right order, but the last bunch don't have their dates/coordinates. I got as far as Les Mis before stopping. -- Peregrine (talk) 15:45, 25 February 2015 (UTC)

Not sure of the protocol here, but the trivia section currently states that "Rip Van Winkel" is a misspelling of "Rip Van Winkle." The use of Winkel in the comic can be correct. (http://i.imgur.com/Z0adeEJ.jpg) The transcription also lists "Rip Can Winkel [sic]" but the comic actually uses "Rip Van Winkel." 108.162.238.181 (talk) (please sign your comments with ~~~~)

This Comic seems to follow the tradition of 647: Scary, 891: Movie Ages, 973: MTV Generation, 1393: Timeghost, and 1477: Star Wars. Making people feel old. --173.245.53.151 16:14, 25 February 2015 (UTC)

Seems like it might have been useful to include some kind of indication of related subject matter from the upper left to the lower right in the "Stories set in the past" section. Mostly looking at the WW II related works. (Bridge/Kwai, Catch-22, Patton, Schindler, Ryan, Pearl Harbor) all seem to make a pretty straight line. Similarly, seeing that relationship between Apocalypse Now and Platoon. Finally, calling the earlier WW II era works 'former period pieces' seems odd. I think I'd still understand which parts were supposed to sound old in those (or maybe it's just that I am old). 199.27.128.215 18:50, 25 February 2015 (UTC)

did nobody see 2001 or was the title text forgotten about? i didnt see 2001 so i cant explain the joke. im pretty sure its just a joke about how it sounds similar, but i dont want to add that explanation if its wrong.TheJonyMyster (talk) 22:55, 25 February 2015 (UTC)

Does Randall exclude the 1984 film The Terminator because the main portion occurs in 1984, or do you suppose it's because the film is not technically obsolete, given the wandering date of the predicted Judgement Day (as well as actual existence of killbots, advanced tactical simulation systems & a large broadband computer network named SkyNet)? It has often occurred to me that the only thing fictional about The Terminator is the existence of a device enabling time travel. ("The Vulcan Science Directorate has determined that time travel is impossible." T'Pol, Enterprise ;) He seems to have left out many notable predictive works which in fact came true, rather than becoming "obsolete". 173.245.55.29 (talk) (please sign your comments with ~~~~)

- even correct predictions are obsolete. Because they change into facts. Let's say on Thursday I predict it will be sunny on Friday. It is sunny on Friday. Now it's Saturday. Is my prediction from Thursday obsolete, or current? --108.162.249.166 05:46, 26 February 2015 (UTC)

- This comic's theme is stories who don't take place on their publication's date. Also, some of the listed stories have a (more or less) historically accurate setting.--108.162.229.165 12:25, 26 February 2015 (UTC)

Whoever wrote the date explanation for "The Time Machine" seems to have used a ridiculous number of significant figures justified by neither the book nor comic (or, for that matter, films). Even more important, the dates aren't even the right order of magnitude. I'm going to fix it, but I just thought I'd leave a comment in case the numbers actually came from somewhere. If they did, please enlighten me. 108.162.216.79 22:23, 26 February 2015 (UTC)

- At least according to the main Wikipedia, the year in which the traveler first meets the Eloi is known precisely. I'm going to leave it rounded, though, so as not to cause confusion, as the the time of the furthest he gets in the future is definitely not known to more than one sigfig.108.162.216.79 22:40, 26 February 2015 (UTC)

- 'Twas I, in my initial (now excised) part-compilation, using the accuracy I could extract from sources like Wiki. And when I tried to add back in the 'range' element (mysteriously lost, and also wanted to add the last column for notes), I kept getting edit conflicts. Sorted now, though. I don't mind the rounding, except for it actually being a known value (a rare thing). (I had also intended to add in the notes that it actually started in/encompassed 'the present', or rather "three years ago", by the timeline of the primary narator, 'though not indicated as such on the chart.) 141.101.98.192 14:45, 27 February 2015 (UTC)

The Star Wars footnote is incorrect: our universe is 13.8B, less th 13B for SW uni = ~1B years. The formation of galaxies puts a *maximum* time difference of 13.4B years, not 0.4B. 199.27.133.136 (talk) (please sign your comments with ~~~~)

- I found that confusing myself - it's correct, just badly written. Our universe is 13.8b years old; the Star Wars universe is 13b years old (800,000 years younger). - Andrew Williams, 10:57BST, 28 February 2015.

Now, where on the graph would "The Day After Tomorrow" be placed, I wonder..? ;) 141.101.98.181 21:57, 3 March 2015 (UTC)

I just read the explanation's reference to Apollo 13 one day sounding like a contemporary movie and thought "I thought it was made not too long after the actual mission" - and then it hit me: we've crossed the line. I didn't realise it was a period piece... 172.71.122.162 10:32, 8 January 2025 (UTC)

I want someone to make a current version of this that updates live as time passes, and can have new works added to it. Heleatunda (talk) 05:49, 26 January 2026 (UTC)