Difference between revisions of "1425: Tasks"

(→Explanation) |

(→Explanation) |

||

| Line 8: | Line 8: | ||

==Explanation== | ==Explanation== | ||

| − | [[Cueball]] appears to be asking [[Ponytail]] to write an app that determines if a given picture is (1) taken in a national park, and (2) a picture of a bird. The first question is generally harder for a human to answer, but easy for an app that has access to location information and a {{w|geographic information system}} (GIS). The second one is easy for a human but much harder for a computer. This illustrates {{w|Moravec's paradox}} from the 1980s in a modern context. By the 1950s computers were useful for tasks like {{w|trajectory optimization}}, {{w|automated theorem proving|generating novel mathematical proofs}}, | + | [[Cueball]] appears to be asking [[Ponytail]] to write an app that determines if a given picture is (1) taken in a national park, and (2) a picture of a bird. The first question is generally harder for a human to answer, but easy for an app that has access to location information and a {{w|geographic information system}} (GIS). The second one is easy for a human but much harder for a computer. This illustrates {{w|Moravec's paradox}} from the 1980s in a modern context. By the 1950s computers were useful for tasks like {{w|trajectory optimization}}, {{w|automated theorem proving|generating novel mathematical proofs}}, {{tvtropes|ArsonMurderAndJaywalking|and}} {{w|English_draughts#Computer_players|the game of checkers}}, so such high-level computation and reasoning tasks that were hard for humans turned out to be relatively easy for them. On the other hand, it turns out to be hard to "give them the skills of a one-year-old when it comes to perception", as Moravec wrote. |

In order to determine whether the user is in a national park, Ponytail plans to determine the user's location using the mobile device. This location will then be cross checked with a {{w|geographic information system}} (GIS) which will be able to determine whether the coordinates lie within a national park boundary. | In order to determine whether the user is in a national park, Ponytail plans to determine the user's location using the mobile device. This location will then be cross checked with a {{w|geographic information system}} (GIS) which will be able to determine whether the coordinates lie within a national park boundary. | ||

Revision as of 04:51, 21 June 2018

| Tasks |

Title text: In the 60s, Marvin Minsky assigned a couple of undergrads to spend the summer programming a computer to use a camera to identify objects in a scene. He figured they'd have the problem solved by the end of the summer. Half a century later, we're still working on it. |

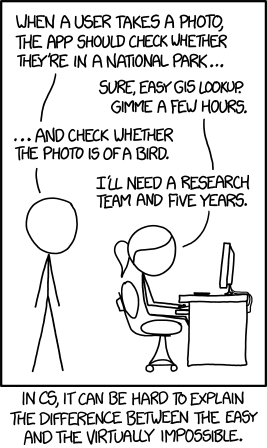

Explanation

Cueball appears to be asking Ponytail to write an app that determines if a given picture is (1) taken in a national park, and (2) a picture of a bird. The first question is generally harder for a human to answer, but easy for an app that has access to location information and a geographic information system (GIS). The second one is easy for a human but much harder for a computer. This illustrates Moravec's paradox from the 1980s in a modern context. By the 1950s computers were useful for tasks like trajectory optimization, generating novel mathematical proofs, and the game of checkers, so such high-level computation and reasoning tasks that were hard for humans turned out to be relatively easy for them. On the other hand, it turns out to be hard to "give them the skills of a one-year-old when it comes to perception", as Moravec wrote.

In order to determine whether the user is in a national park, Ponytail plans to determine the user's location using the mobile device. This location will then be cross checked with a geographic information system (GIS) which will be able to determine whether the coordinates lie within a national park boundary.

Determining whether an image is of a given kind of natural object is far more difficult. This task falls into the area of computer vision. One of the goals in computer vision is to detect and classify objects within an image. This is a very challenging task for a number of reasons.

- Firstly, humans use size, edge-assignment, movement, and stereoscopic vision when looking at a scene (not a picture of a thing, but of the thing itself) to discern individual objects and then categorize them as foreground or background.[1] A photograph, however, is a static, monoscopic image that can only provide size and edge-assignment clues. Humans are only able to discern objects from background in photographs by comparing the photo against all of the things they've seen and everything they've learned about those things over the course of their life and identifying matching patterns.[2]

- Secondly, the quality of the photograph will have an impact on a computer's ability to match patterns. For example, the object in the photograph might be partially visible or occluded. In the case of a living bird, additional complications arise from the variations among individual birds of the same species and differences in pose (flying, perching in a tree, etc.). Differentiating between visually similar objects can result in false positives. For example, is it a photo of a bird in flight or a plane (or superman!)? Ponytail's estimate of 5 years may be overly optimistic (see 678: Researcher Translation).

Today's state-of-the-art algorithms for solving this kind of task mostly use local features (e.g. SIFT or SURF in combination with a support vector machine or convolutional neural network).

The subtitle refers to "CS", which is a common acronym for "Computer Science", of which artificial intelligence and computer vision are sub-disciplines.

The title text mentions The Summer Vision Project and Marvin Minsky of MIT. In the summer of 1966, he asked his undergraduate student Gerald Jay Sussman to "spend the summer linking a camera to a computer and getting the computer to describe what it saw" ([1]). Seymour Papert drafted the plan, and it seems that Sussman was joined by Bill Gosper, Richard Greenblatt, Leslie Lamport, Adolfo Guzman, Michael Speciner, John White, Benjamin, and Henneman - in case the multiple Wikipedia links don't give it away, know that this is sizable cross-section of the AI researchers of the period). The project schedule allocated one summer for the completion of this task. The required time was obviously significantly underestimated, since dozens of research groups around the world are still working on this topic today.

A month after this comic came out, Flickr responded with a prototype online tool to do something similar to what comic describes, using its automated-tagging software. According to them, the bird solution "took us less than 5 years to build, though it's definitely a hard problem, and we've still got room for improvement".

Transcript

- [Ponytail sitting at a computer with Cueball standing behind her.]

- Cueball: When a user takes a photo, the app should check whether they're in a national park...

- Ponytail: Sure, easy GIS lookup. Gimme a few hours.

- Cueball: ...and check whether the photo is of a bird.

- Ponytail: I'll need a research team and five years.

- In CS, it can be hard to explain the difference between the easy and the virtually impossible.

References

Discussion

the source of title text maybe is Szeliski, Computer Vision: Algorithms and Applications (2010), p. 10. --valepert (talk) 06:59, 24 September 2014 (UTC)

Google’s Artificial Brain Learns to Find Cat Videos might be useful as a description of the problem 108.162.250.219 08:34, 24 September 2014 (UTC)

- Sorry for editing your comment but external links have different syntax that internal links so it wasn't working. -- Hkmaly (talk) 11:21, 24 September 2014 (UTC)

Nice Superman joke there, Pudder! --141.101.99.49 10:26, 24 September 2014 (UTC)

- It had been removed in an edit, so I shoehorned in back in :P --Pudder (talk) 12:25, 24 September 2014 (UTC)

Isn't there an xkcd where the estimate of 5 years of work is equivalent to "might take forever?" Rtanenbaum (talk) 13:16, 24 September 2014 (UTC)

- I'm pretty sure you're refering to 678. 173.245.52.132 15:00, 25 September 2014 (UTC)

The link in the description is to a document by Seymour Papert and the book on the project is also by Papert. Is there any contemporary evidence that it was actually Minsky who assigned the project? I think he just got interested in it later. 14:17, 24 September 2014 (UTC)

678: Researcher Translation is probably what you're thinking of, Rtanenbaum. Ndgeek (talk) 17:44, 24 September 2014 (UTC)

Is it possible that Randall's selection of bird rather than another naturally occurring object is a subtle reference to the Birdsnap app (http://engineering.columbia.edu/it-crow-or-raven-new-birdsnap-app-will-tell-you-0) which has solved some of the aspects of this problem? 173.245.48.137 22:02, 27 September 2014 (UTC)

Hopefully I can add that this also seems to make reference to the U.S. Forest Service intention to make everyone have a permit to take pics, etc., in national parks. https://www.yahoo.com/travel/dont-take-that-picture-the-u-s-forest-service-might-98484656432.html 108.162.216.21 (talk) (please sign your comments with ~~~~)

Post the picture to an online forum, say it's a bird, if it's not everyone will correct you as per http://xkcd.com/386/, so scrape forum and if there's a lot of attention it's not a bird, if there isn't much attention it probably is a bird. 141.101.99.78 23:06, 3 October 2014 (UTC)

A dev team at Flickr took this comic as a challenge, and set up a PoC at http://parkorbird.flickr.com/ (that seems to work fairly well). --108.162.210.135 20:08, 20 October 2014 (UTC)

- I was duly impressed. It doesn't recognize big bird very well, though. ;) Suspender guy (talk) 20:26, 17 February 2016 (UTC)

A 'picture of a bird' from a CS perspective is a reverse engineering problem. The picture is a 2 dimensional rendering of a 3-dimensional world and a 'bird' is a 3-dimensional object. It takes years for the mind of a newborn human to be able to recognize a majority of objects based on their 'first look' at a stereoscopic (two-eyes) image presented by their visual cortex. The software equivalency of this would be to create a 3 dimensional representation of objects and create a linear-algebra algorithm that can define the statistical probability that any given shape is within a certain degree of exclusion a matrix representation of the target shape (area) of the 3 dimensional object (bird) based on distance (using spacial reconstruction). It's not impossible, it's just really really hard. - nerd answer 173.245.54.166 (talk) (please sign your comments with ~~~~)

- To be honest I don't think it is impossible to replicate any function of human intelligence and mental capacity on a computer system. It just requires sufficient processing ability, appropriate hardware, and of course, an understanding of how humans do it in the first place. -Pennpenn 108.162.250.162 03:29, 17 September 2015 (UTC)

Or just give Google a little less than two years, and they'll make Google Cloud Vision API for you Gpk (talk) 20:39, 13 June 2016 (UTC)

I read somewhere that when you ask CS/IT specialist for a probable ETA for solving an interesting problem, you need to multiply the given time to the ETA by 4 and take the next larger unit (a minute becomes 4 hours, an hour becomes 4 days etc.). Can't find the source of that though. 141.101.70.229 15:47, 12 September 2016 (UTC)

GIS being "easy"

All these years later, I still struggle with the classification of "are we in a national park" as "easy"..

It 'only' requires a functioning GPS-system. A military super-project, whose initial setup cost 12 billion, still costs ~2 million a day, and whose principles of operation depend on both special and general relativity for correctness. And that's before we add the record-keeping and (internet?)logistics involved with providing each phone an accurate GIS-database. The OpenStreetMap (most likely free/gratis source of this type of data, for a cheap app) is a massive undertaking!

(sarcasm on) GIS-lookup sure is easy! Only took a minor Manhattan-project, a literal Einstein, and an army of internet volunteers to solve!(sarcasm off)

(I'm leaving out mobile internet access while in said National Parks (Telecom operators are among the wealthiest companies in the world, and those phone-towers-disguised-like-trees don't come cheap...), because the App would probably be shipped with a hardcoded park-database, not do live queries.)

-- Jules @ 162.158.91.77 08:13, 18 May 2020 (UTC)

- This is about implementation of something existing, not inventing it from scratch. The use of the word "app" implies, that this comic is happening in the smartphone area, so GPS on phones should be a regular thing. --Lupo (talk) 09:57, 18 May 2020 (UTC)

- "app" sets the real-world context, but the punchline is about the comparative hardness in CS.

- For the pragmatic app-developer, "previously solved" equals "easy"; for a doctorate in computational theory, it doesn't :-)

- -- Jules @ 162.158.91.77 12:16, 18 May 2020 (UTC)

- That might be true, but this comic is definitely about developing an app, so it doesn't matter if GPS involves complicated hard- and software setups outside of the app or not. And unless you focus on the theoretical work also for a computer scientist, it is easy to use established GPS methods. --Lupo (talk) 12:45, 18 May 2020 (UTC)

now deep learning is common you not need research team and five years anymore

- And it took about five years since the comic was posted to get to that point...

This comic is referring to doing a GIS lookup which is a glorified sql Query which has nothing to do with GPS and the the USGS spatial data a GIS database is commonly populated with is not derived from GPS information anyway. A GIS Lookup IS easy. Gathering the spatial data is difficult, though as previously mentioned its already widely and freely available for use. --PlatterMonkous

- The GIS data is being looked at to determine if GPS-derived metadata lies within one of its boundaries, surely? Without GPS, the query has no sensible question to ask.

- (Then again, none of my own pictures have that sort of EXIF information. Either they're taken on a 'dumb' digital camera, that doesn't have inbuilt GPS, or even if they're done via my GPS+Camera-equipped tablet (rare) I've likely not allowed the one to be fed data that the other one knows. If it's even turned on. But the comic scenario clearly assumes otherwise.) 172.70.86.62 20:21, 10 November 2022 (UTC)

I think that, like in a number of other comic explanations, the explanation of the humour has given way to the technical exposition of the situation. What made me chuckle about this comic is the old adage in the software industry that: It takes 5% of the time to implement the first 95%, but 95% of time to complete the last 5%. Even when experienced programmers correctly identify the difficult element of a problem and attempt to compensate for that difficulty in their implementation schedules, they can still be wildly off the mark. In this case, 60 years and counting... 172.71.94.28 10:55, 9 August 2023 (UTC)

The year is 2024, and there is an ArsTechnica article about the problem in this comic now being solved. https://arstechnica.com/information-technology/2024/01/famous-xkcd-comic-comes-full-circle-with-ai-bird-identifying-binoculars/ 172.70.210.41 22:24, 17 January 2024 (UTC)

- Updated to add credit where credit is due, the research team in our reality that created the technology is the Cornell Lab of Ornithology in the Center for Avian Population Studies and Macaulay Library: https://ebird.org/about/staff -- No doubt if Ponytail was the lead the staff could've done it in half the time! 162.158.90.24 22:32, 17 January 2024 (UTC)

The rewrite of the explanation is really long overdue! If it's hard to start from scratch, someone could request GPT-4 to make a plan on how to update the article, and then use the ideas for inspiration 162.158.151.152 (talk) 20:44, 13 March 2024 (please sign your comments with ~~~~)

- If you think it could do with a rewrite, rewrite it yourself. (Stay away from GPT, though, still likely to give an unsatisfactory explanation. If not downright hallucinating.) 172.70.86.179 21:01, 13 March 2024 (UTC)

The explanation of bird identification assumed that a static picture was all the information available to the app. There is no reason the app can't use additional data for this problem (as it does for problem 1). There are various ways the App could estimating range (stereo pictures, series of images with different focal lengths, distance sensors). Could use images beyond the visible range. Could use multiple frames or moving images to figure parallax, and help differentiate static from moving objects. (Sensors in the camera could indicate how the camera moved to inform interpretation of time based imaging.) All of these techniques were possible when the comic was posted, although they present interesting problems. I updated the explanation to try to expand the possibilities. Put in this comment in case what I put in the explanation wasn't clear. 172.68.22.108 03:56, 24 April 2025 (UTC)

It is funny that this tool from Simon Willison - just did this task - https://tools.simonwillison.net/is-it-a-bird, 01:55, 13 January 2026 (UTC)