Difference between revisions of "3210: Eliminating the Impossible"

m |

(→Explanation) |

||

| (2 intermediate revisions by 2 users not shown) | |||

| Line 10: | Line 10: | ||

==Explanation== | ==Explanation== | ||

| − | {{incomplete|This page was created | + | {{incomplete|This page was created by the one thing that actually was in the car. Don't remove this notice too soon.}} |

| + | |||

| + | The discussion in this comic plays upon the phrase originating from the fictional Sherlock Holmes (and therefore also his author, Arthur Conan-Doyle) that "[https://www.goodreads.com/quotes/1196-when-you-have-eliminated-all-which-is-impossible-then-whatever When you have eliminated all which is impossible, then whatever remains, however improbable, must be the truth,]" which describes Holmes' {{w|abductive reasoning}} used to solve the crimes and mysteries set before him. | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[White Hat]] is expounding this principle, to [[Cueball]], as some key part of logic for some undisclosed purpose. Cueball argues that human error - namely, making a mistake in the 'elimination' process - is also possible, and claims that the logic is faulty on this premise. When White Hat points out that the logic is a guideline for problem-solving, Cueball argues that the possibility of human error when operating on this logic makes the logic unsound. | ||

| + | |||

| + | This, of course, ignores the entire point of the original statement: {{tvtropes|RealityIsUnrealistic|something being ''unlikely'' does not make it ''untrue''}}, and ignoring reality because it is "unlikely" is both absurd and counterproductive to the process of solving a problem. | ||

| + | |||

| + | In the final panel, Cueball demonstrates a practical example of human error causing this issue. When a person is looking for their possessions, their first option is to search the house in which they presently are, while their second option is to search their mode of transportation (especially in the case of possessions that are regularly brought to and from other locations). White Hat agrees that he himself has been in the situation where he has searched the entire house, not found what he is looking for, assumes it is in the car, and then fails to locate it in the car as well. This, too, demonstrates the failing in Cueball's argument against the logic: there are other locations besides "in my house" and "in my car"{{citation needed}}, and so even in the instance that the searcher ''has'', in fact, searched every location in the house, they have not finished eliminating the impossible. Indeed, many people have searched both their home and their car (thoroughly and repeatedly) and ultimately found the object they were looking for in another building entirely. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The title text mockingly rephrases the quote as the {{tvtropes|TheoryOfNarrativeCausality|Law of Narrative Causality}} - in short, things happening because the plot requires them to happen. | ||

==Transcript== | ==Transcript== | ||

Latest revision as of 23:15, 20 February 2026

| Eliminating the Impossible |

Title text: 'If you've eliminated a few possibilities and you can't think of any others, your weird theory is proven right' isn't quite as rhetorically compelling. |

Explanation[edit]

| This is one of 67 incomplete explanations: This page was created by the one thing that actually was in the car. Don't remove this notice too soon. If you can fix this issue, edit the page! |

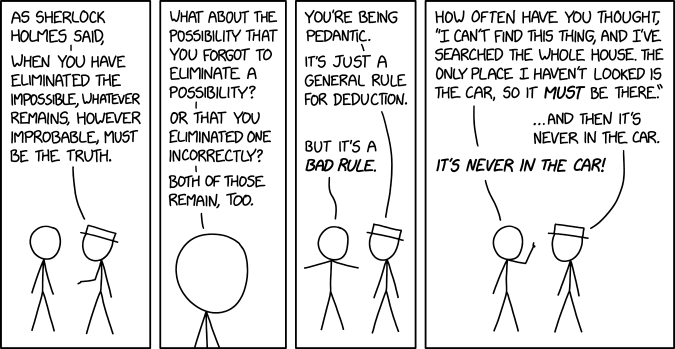

The discussion in this comic plays upon the phrase originating from the fictional Sherlock Holmes (and therefore also his author, Arthur Conan-Doyle) that "When you have eliminated all which is impossible, then whatever remains, however improbable, must be the truth," which describes Holmes' abductive reasoning used to solve the crimes and mysteries set before him.

White Hat is expounding this principle, to Cueball, as some key part of logic for some undisclosed purpose. Cueball argues that human error - namely, making a mistake in the 'elimination' process - is also possible, and claims that the logic is faulty on this premise. When White Hat points out that the logic is a guideline for problem-solving, Cueball argues that the possibility of human error when operating on this logic makes the logic unsound.

This, of course, ignores the entire point of the original statement: something being unlikely does not make it untrue, and ignoring reality because it is "unlikely" is both absurd and counterproductive to the process of solving a problem.

In the final panel, Cueball demonstrates a practical example of human error causing this issue. When a person is looking for their possessions, their first option is to search the house in which they presently are, while their second option is to search their mode of transportation (especially in the case of possessions that are regularly brought to and from other locations). White Hat agrees that he himself has been in the situation where he has searched the entire house, not found what he is looking for, assumes it is in the car, and then fails to locate it in the car as well. This, too, demonstrates the failing in Cueball's argument against the logic: there are other locations besides "in my house" and "in my car"[citation needed], and so even in the instance that the searcher has, in fact, searched every location in the house, they have not finished eliminating the impossible. Indeed, many people have searched both their home and their car (thoroughly and repeatedly) and ultimately found the object they were looking for in another building entirely.

The title text mockingly rephrases the quote as the Law of Narrative Causality - in short, things happening because the plot requires them to happen.

Transcript[edit]

| This is one of 46 incomplete transcripts: Don't remove this notice too soon. If you can fix this issue, edit the page! |

[White Hat and Cueball are standing together and talking. White Hat has one hand slightly raised.]

- White Hat: As Sherlock Holmes said,

- White Hat: When you have eliminated the impossible, whatever remains, however improbable, must be the truth.

[Close-up of Cueball's head.]

- Cueball: What about the possibility that you forgot to eliminate a possibility?

- Cueball: Or that you eliminated one incorrectly?

- Cueball: Both of those remain, too.

[Zoom back out to show both parties. Cueball is holding his arms out.]

- White Hat: You're being pedantic.

- White Hat: It's just a general rule for deduction.

- Cueball: But it's a bad rule.

[Cueball is now holding up one finger.]

- Cueball: How often have you thought, "I can't find this thing, and I've searched the whole house. The only place I haven't looked is the car, so it must be there."

- White Hat: ...And then it's never in the car.

- Cueball: It's never in the car!

Discussion

I’ve found that when looking for an item, I’ll search harder and more thoroughly in the places where the item is supposed to be, which is just frustrating and usually unsuccessful. Then I realized that if the item isn’t where it’s supposed to be, then it’s somewhere it isn’t supposed to be - so I start looking in those places. 170.64.111.76 20:51, 20 February 2026 (UTC)

It also assumes exclusion of the middle. MithicSpirit (talk) 20:59, 20 February 2026 (UTC)

These guys sure are some professors of logic (I'm not sure if they own any doghouses, is what I mean). Fephisto (talk) 21:07, 20 February 2026 (UTC)

As and when the Explanation gets written (I imagine that someone's right in the middle of that now), it must be noted that Sherlock Holmes's self-proclaimed "Deductive reasoning" is really Abductive reasoning. (I actually blame Sir Arthur, rather than Sherlock (or 'narrator' Watson), for that error... But then he also believed in fairies, so obviously he's less than perfectly rational.) 81.179.199.253 21:17, 20 February 2026 (UTC)

- Well, nobody did do anything with it, in the last hour or so, so I scrawled something pretty basic for others to ruthlessly dismember and 'remember' in their own prefered fashion. 81.179.199.253 22:27, 20 February 2026 (UTC)