3210: Eliminating the Impossible

| Eliminating the Impossible |

Title text: 'If you've eliminated a few possibilities and you can't think of any others, your weird theory is proven right' isn't quite as rhetorically compelling. |

Explanation

| This is one of 67 incomplete explanations: This page was created by the one thing that actually was in the car. Don't remove this notice too soon. If you can fix this issue, edit the page! |

The discussion in this comic plays upon the phrase originating from the fictional Sherlock Holmes (and therefore also his author, Arthur Conan-Doyle) that "When you have eliminated all which is impossible, then whatever remains, however improbable, must be the truth," which describes Holmes's abductive reasoning used to solve the crimes and mysteries set before him. The point of the original statement is that something being unlikely does not make it untrue, and ignoring reality because it is "unlikely" is both absurd and counterproductive to the process of solving a problem. However, this statement is a fallacy, as nobody is omniscient so it is impossible to rule out all alternatives.

In the real world, it is never true that eliminating the impossible leaves only a single possible outcome. There are always vast numbers of events that are technically possible, but so vastly improbable that they would be unlikely to ever be observed, even if every subatomic particle in the universe were a universe itself, and were to be observed from Big Bang to heat death. An example would be quantum tunneling of a macroscopic object over a long distance... such as a set of keys from inside a house out to a car. In practice, such events are usually dismissed from consideration.

White Hat is expounding this principle, to Cueball, as a logical step for some undisclosed purpose. Cueball argues that human error - namely, making a mistake in the 'elimination' process - is also possible, and claims that the logic is faulty on this premise. When White Hat points out that the logic is a guideline for problem-solving, Cueball argues that the possibility of human error when operating on this logic makes the approach unsound. If there is one true version of events, then finding it by this process requires classifying all other possibilities as impossible. While that might be possible for a constrained problem like a detective story or multi-option question, many daily situations require eliminating vast numbers of possibilities while lacking sufficient information to be truly sure that the possibilities have been exhausted.

In the final panel, Cueball demonstrates a practical example of human error causing this issue. When a person is looking for their possessions, their first option is to search the house in which they presently are, while their second option is to search their mode of transportation (especially in the case of possessions that are regularly brought to and from other locations). White Hat agrees that he himself has been in the situation where he has searched the entire house, not found what he is looking for, assumes it is in the car, and then fails to locate it in the car as well. There are other possibilities, but the tendency to jump to conclusions (possibly by misuse of the quote) can lead to those being ignored. Additional possibilities:

- The house has not been fully searched, with the item left in some obscured corner, a clothing pocket that is in the laundry, or even a vent or pipe that one could not practically access.

- The car has not been fully searched, because the item slid between two seats or was deeper in a glove compartment than the searcher thought possible.

- It is common for people to fail to see a thing even though it is present, sometimes even clearly in view, because of momentary cognitive glitching, poor assumptions, or more fundamental cognitive failures such as visual agnosia. Another Holmes quotation is relevant: "You see, but you do not observe."

- The searcher forgets that they took the item to some other location, or wishfully ignores that possibility because it is far away and/or inconvenient to search.

- The searcher has never taken the item anywhere other than the house or car, but is unaware that someone or something else moved it.

- The item may have been destroyed or altered in a way that makes it unrecognizable when found.

The title text goes further in deconstructing how the quote might result in a logically incorrect argument from ignorance. In fiction, there is a Law of Narrative Causality, by which events are successfully resolved in the way that the plot requires them to be resolved; therefore, stating this approach as a logical rule would normally be narratively unsatisfying. When Sherlock Holmes first uses the phrase in The Sign of the Four, he "deduces" that Watson had sent a telegram at the post office instead of doing anything else by observing that he had not written a letter and that he already had a good stock of postcards and stamps. Holmes neglects the possibility that Watson had sent a letter that he had written sometime previously, or any other possibility, yet he happens to be right because it would be unsatisfying were he to be wrong. Humorously, he claims in the same chapter that "I never guess".

Sherlock may have more accurately, yet less memorably, phrased the maxim as "When you have eliminated what is likely, the truth must be a more improbable outcome".

In The Long Dark Tea-time of the Soul, Douglas Adams commented on this Holmesian maxim:'The impossible often has a kind of integrity to it which the merely impossible lacks. How often have you been presented with an apparently rational explanation of something that works in all respects other than one, which is just that it is hopelessly improbable? Your instinct is to say, "Yes, but he or she simply wouldn't do that." ''Well, it happened to me today, in fact,' replied Kate.

'Ah, yes,' said Dirk, slapping the table and making the glasses jump, 'your girl in the wheelchair [who was constantly mumbling stock prices from the day before]—a perfect example. The idea that she is somehow receiving yesterday's stock market prices out of thin air is merely impossible, and therefore must be the case, because the idea that she is maintaining an immensely complex and laborious hoax of no benefit to herself is hopelessly improbable. The first idea merely supposes that there is something we don't know about, and God knows there are enough of those. The second, however, runs contrary to something fundamental and human which we do know about. We should therefore be very suspicious of it and all its specious rationality.'

Transcript

| This is one of 46 incomplete transcripts: Don't remove this notice too soon. If you can fix this issue, edit the page! |

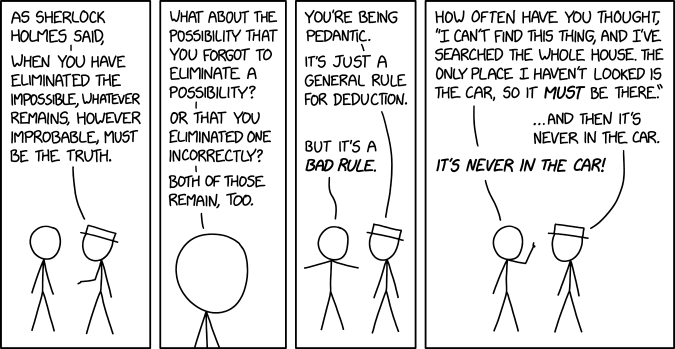

- [White Hat and Cueball are standing together and talking. White Hat has one hand slightly raised.]

- White Hat: As Sherlock Holmes said,

- White Hat: When you have eliminated the impossible, whatever remains, however improbable, must be the truth.

- [Close-up of Cueball's head.]

- Cueball: What about the possibility that you forgot to eliminate a possibility?

- Cueball: Or that you eliminated one incorrectly?

- Cueball: Both of those remain, too.

- [Zoom back out to show both. Cueball holds his arms out.]

- White Hat: You're being pedantic.

- White Hat: It's just a general rule for deduction.

- Cueball: But it's a bad rule.

- [Cueball holds up one finger.]

- Cueball: How often have you thought, "I can't find this thing, and I've searched the whole house. The only place I haven't looked is the car, so it must be there."

- White Hat: ...and then it's never in the car.

- Cueball: It's never in the car!

Discussion

I’ve found that when looking for an item, I’ll search harder and more thoroughly in the places where the item is supposed to be, which is just frustrating and usually unsuccessful. Then I realized that if the item isn’t where it’s supposed to be, then it’s somewhere it isn’t supposed to be - so I start looking in those places. 170.64.111.76 20:51, 20 February 2026 (UTC)

It also assumes exclusion of the middle. MithicSpirit (talk) 20:59, 20 February 2026 (UTC)

- I think you're kind of right, but it's a weird situation. Disjunction elimination does not require LEM. I can imagine that we have established some list of n "possibilities" p0, p1, ..., pn. What does it mean that these are the only possibilities? Naturally, it means p0 ∨ p1 ∨ · · · ∨ pn. Now, if we eliminate all but the kth possibility, that means we have ¬p0, ¬p1, ..., ¬pk-1, ¬pk+1, ..., ¬pn. By repeated use of disjunction elimination, this proves pk intuitionistically, so the kth possibility ("whatever remains") is provable ("must be the truth"). The problem with this approach is proving the original disjunction. How did we show to begin with that one of those n possibilities must hold? To do that intuitionistically requires actually proving one of those statements to begin with. And since only one of them is true, we must have already proved pk, rendering this argument pointless. Still, it technically is valid. EebstertheGreat (talk) 14:20, 21 February 2026 (UTC)

- I originally interpreted it as taking the collection of all (relevant?) propositions, excising the false ones, and deducing that anything that was not excised must be true. Effectively meaning that that if ¬p does not hold then p must hold, which is EM. I think your interpretation is incorrect because the comic does not require the collection of "whatever remains" to be nonempty, so we don't necessarily have the disjunction. MithicSpirit (talk) 20:43, 21 February 2026 (UTC)

These guys sure are some professors of logic (I'm not sure if they own any doghouses, is what I mean). Fephisto (talk) 21:07, 20 February 2026 (UTC)

As and when the Explanation gets written (I imagine that someone's right in the middle of that now), it must be noted that Sherlock Holmes's self-proclaimed "Deductive reasoning" is really Abductive reasoning. (I actually blame Sir Arthur, rather than Sherlock (or 'narrator' Watson), for that error... But then he also believed in fairies, so obviously he's less than perfectly rational.) 81.179.199.253 21:17, 20 February 2026 (UTC)

- Well, nobody did do anything with it, in the last hour or so, so I scrawled something pretty basic for others to ruthlessly dismember and 'remember' in their own prefered fashion. 81.179.199.253 22:27, 20 February 2026 (UTC)

I think its pretty nice how this comics number is a countdown from 3. Xkdvd (talk) 22:57, 20 February 2026 (UTC)

By the way, meant to say earlier... just today (well, the day just before the midnight just gone), I spent a few moments trying to help someone find a single glove. They'd looked various places, and I went out to look in the car (twice, actually, because first I just checked the 'normal' places, footwells, door-pockets... then realised I hadn't actually checked the glove-compartment itself (which I don't think I've ever used to store gloves, of course, but I'd have looked silly if I hadn't gone back and checked it once it had occured to me) so out I went again) in order to not find the glove. Cue, later, the revelation that it had been in a bag (in the house) all along. And this was all mere hours before Randall published this comic. So, as we all used to say on the now defunct Fora, "GOOMHR!" 81.179.199.253 00:24, 21 February 2026 (UTC)

It's also possible to miss an item in a space you've searched. For instance, as a 12- or 13-year-old I once concluded that something (I forget what it was) must not be in my room, because I'd partitioned the rectangular box defined by the walls, floor and ceiling and searched each of the partitions. It turned out to be outside that box but still inside my room, because it was on the windowsill. Promethean (talk) 00:39, 21 February 2026 (UTC)

I actually did find it in the car though.--2604:3D09:84:4000:6FFB:F472:7679:FF75 02:34, 21 February 2026 (UTC)

Reminds me of this from Math Hysteria by Ian Stewart: 'As I have often stated, when you have eliminated the impossible, then whatever remains, however improbable ... remains improbable,' said Holmes, deflated. 'There's probably something altogether different going on, and you've missed it. But don't quote me on that,' he warned. Arcorann (talk) 09:23, 21 February 2026 (UTC)

- I was going to get that actual book, before Christmas (after I'd decided what other book I was getting for someone else, when visiting a good bookshop with a nice selection of not-necessarily-new publications), as there's still just about space for it on my 'Pratchett-adjacent' bookshelves next to his (and specifically Jack Cohen's) other stuff. Which I'm a bit sorry now that I never got signed by them (both, where relevent) while I still could, the few times we had all crossed paths. 81.179.199.253 14:25, 21 February 2026 (UTC)

If it's not in the car, it's in the cdr. --2A02:3100:25A0:9400:6CEB:97FF:FE5B:8BDC 11:06, 21 February 2026 (UTC)

- Yeth. 174.130.97.11 (talk) 14:10, 21 February 2026 (please sign your comments with ~~~~)

To be fair, it is SHERLOCK HOLMES making the comment. He literally means when you have actually eliminated all other possibilities. And he was pedantic enough to be thorough about it. Dúthomhas (talk) 21:27, 21 February 2026 (UTC)

- Not at all; upon re-reading The Sign of the Four (his first use of the phrase) he most certainly has not eliminated all other possibilities in both his uses of the phrase. Hilariously, he then comments "I never guess" Nerd1729 (talk) 22:01, 21 February 2026 (UTC)

- I am unsure how you make that claim. Holmes is quite pedantic in explaining the peculiarities of how he arrived at both deductions, and he is a stickler for details and minutiae of his environment — the guy studies tobacco remains to the point that he can tell you who’s buying it when he finds it someplace uncouth. Unless you suggest that Holmes should suppose Watson — a man bound by habit and practicalities — should act out of character and wander through the _peculiar reddish_ earth just to mess with Holmes, or in the second instance that we have knowledge of some _other_ method of entering that room that Doyle did not? ’Cause I don’t think that _abnormal_ behavior or circumstances qualifies as the normal possibilities being eliminated before considering the _improbable_. I will agree that Holmes was pretty full of himself, tho. Dúthomhas (talk) 1:24, 22 February 2026 (UTC)

- Holmes deduces that Watson had sent a telegraph because he had not seen Watson write a letter that morning and Watson had an adequate collection of stamps and postcards. What about the possibility then that Watson had written a letter the previous day, only to send in the morning? Nerd1729 (talk) 02:59, 22 February 2026 (UTC)

- One must also assume that someone would tread in that earth only upon entering the post office, as opposed to while passing by it, and that nobody kicked or dropped any of that earth elsewhere. That the stamps and postcards on view in the desk weren't purchased on that very trip. That Watson couldn't have bought stamps or postcards, e.g. in the mistaken belief that he'd run out. That there was no other possible reason to enter the post office, e.g. to make some inquiry. BunsenH (talk) 04:33, 22 February 2026 (UTC)

Add comment

Add comment

- One must also assume that someone would tread in that earth only upon entering the post office, as opposed to while passing by it, and that nobody kicked or dropped any of that earth elsewhere. That the stamps and postcards on view in the desk weren't purchased on that very trip. That Watson couldn't have bought stamps or postcards, e.g. in the mistaken belief that he'd run out. That there was no other possible reason to enter the post office, e.g. to make some inquiry. BunsenH (talk) 04:33, 22 February 2026 (UTC)

- Holmes deduces that Watson had sent a telegraph because he had not seen Watson write a letter that morning and Watson had an adequate collection of stamps and postcards. What about the possibility then that Watson had written a letter the previous day, only to send in the morning? Nerd1729 (talk) 02:59, 22 February 2026 (UTC)

- I am unsure how you make that claim. Holmes is quite pedantic in explaining the peculiarities of how he arrived at both deductions, and he is a stickler for details and minutiae of his environment — the guy studies tobacco remains to the point that he can tell you who’s buying it when he finds it someplace uncouth. Unless you suggest that Holmes should suppose Watson — a man bound by habit and practicalities — should act out of character and wander through the _peculiar reddish_ earth just to mess with Holmes, or in the second instance that we have knowledge of some _other_ method of entering that room that Doyle did not? ’Cause I don’t think that _abnormal_ behavior or circumstances qualifies as the normal possibilities being eliminated before considering the _improbable_. I will agree that Holmes was pretty full of himself, tho. Dúthomhas (talk) 1:24, 22 February 2026 (UTC)