2726: Methodology Trial

| Methodology Trial |

Title text: If you think THAT'S unethical, you should see the stuff we approved via our Placebo IRB. |

Explanation

| This is one of 62 incomplete explanations: Created by a PLACEBO RESEARCHER - Please change this comment when editing this page. Do NOT delete this tag too soon. If you can fix this issue, edit the page! |

When testing the efficacy of a potential medical treatment, researchers compare subjects who received the treatment against subjects who received a placebo. Usually each subject does not know whether they received the treatment or placebo, and neither do the practitioners, until the end of the trial. This distinguishes the actual effects of the treatment from the effects of simply participating in a study. People who receive a placebo (or an ineffective treatment) often believe their treatment is working due to such causes as paying more attention to one's health or expecting to feel better. This misattribution of effect to a non-treatment is called the "placebo effect".

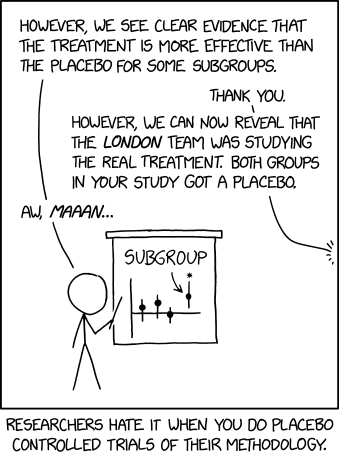

In this comic a team of researchers appears to have studied some medical treatment, using a placebo controlled test. They present their findings in which a particular subset of participants (out of at least four distinct groups) shows an apparently significant result. The graph shows that three groupings have results whose error-bars indicate that they might easily have zero (or neutral) true effects, if not negative ones. But, even at the lowest extent of the accepted uncertainty, the fourth stands out as definitively having some degree of positive effect (of whatever kind this particular graph is plotting).

However, it is revealed that the 'treatment' they were given was also a placebo. Their own study was the subject of a placebo controlled test conducted on their methodology. They were the placebo group, while a different team presumably used the exact same methodology to study the real treatment. Thus, all of this team's findings were due to the placebo effect, or else the trial size and scope allowed a purely statistical 'blip' to occur, instead of there being any real merit to the "treatment". This indicates that their methodology shouldn't be used for any real world applications.

The particular flaw in the methodology appears to be dividing two few subjects into too many sub-groups, allowing a chance cluster of anomalous results to overly influence an apparent result. The researcher did find significance in one sub-group, even though in reality there was no signal, just noise, since it was all placebo groups. This references the same p-hacking problem as 882: Significant. Only in this case the researcher themself is the subject of the real trial.

If the non-placebo study had the exact same size and design (as it should have, in such a meta-study), it would cast doubt upon whether any similar-looking findings in London were significant. Especially if they also found that the same subgroup were again exhibiting the sole significant effect, which might reveal an inbuilt flaw in the procedure. On the other hand, it could just further show how likely any particular grouping was to falsely show a result; if all groups had apparently benefited, the chances are that most of them were correct, whether or not 2268: Further Research is Needed.

Treatments can be more effective on specific subgroups of the population; for example, an anti-cancer drug might only work against specific mutations that cause cancer. But any such result needs to have appropriate statistical significance and new subjects from that subgroup should be tested to ensure the result is repeated.

The title text points out how the experiment has almost certainly violated some set of ethical standards, because one researcher offers what he believes to be genuine treatment to a large number of participants only for a third party (the offscreen speaker) to replace all his medicine with placebos, ultimately deceiving the patients. The title text references that it was approved by a genuine Institutional Review Board (IRB), the group which decides whether a proposed experiment is ethical to perform. However they also have a "placebo IRB", presumably made up of people who have no qualifications to make such judgements well, or perhaps not made up of people at all, but simply a mechanism for generating random decisions.

Transcript

| This is one of 41 incomplete transcripts: Do NOT delete this tag too soon. If you can fix this issue, edit the page! |

- [Cueball stands in front of a poster holding a pointer. The poster shows a scatter plot with four points and error bars, with one data point labeled "Subgroup" is marked with an asterisk and is placed somewhat higher up than the other three points.]

- Cueball: However, we see clear evidence that the treatment is more effective than the placebo for some subgroups.

- Off-panel voice: Thank you.

- Off-panel voice: However, we can now reveal that the London team was studying the real treatment. Both groups in your study got a placebo.

- Cueball: Aw, maaan...

- [Caption below panel]

- Researchers hate it when you do placebo controlled trials of their methodology.

Discussion

Woah! This is the first time I've seen a new comic without an explanation. It's pretty weird. SilverTheTerribleMathematician (talk) 02:36, 19 January 2023 (UTC)

- You just need to have checked at the right (or wrong?) time, which is different every publication day so you can't generally predict it. But at least three readers find empty explanations every week, and now it's your turn!. OR, maybe this is just the first time you've unknowingly checked the placebo wiki... ;) 172.70.91.75 02:54, 19 January 2023 (UTC)

04:10, 19 January 2023 (UTC)~ Comment on the title text. IRB is an Institutional Review Board, which I guess is a committee that decides if research is ethical and ok to do. The title text refers g to a placebo IRB, which I suppose is a fake IRB that can approve research as part of an experiment to determine the real effects of IRBs. Or something.

Why would this experiment be more unethical than any regular placebo trial? In either case you're telling patients they're getting actual medication when in reality they're getting sugar pills (or whatever you use as placebo). Bischoff (talk) 08:22, 19 January 2023 (UTC)

- In a normal trial, the patients are told the researcher is giving out some candidate medicine and some placebo - typically they'd have a 50% chance of receiving a medicine that may help them. In this case, none of the treatments given will actually contain the active ingredient. I suppose it depends what you consider the "trial" (whether it includes all the test sites or just the one Cueball is running).172.70.85.46 10:40, 19 January 2023 (UTC)

- Placebo-based trials may have a threshold at which particularly significant results (as detected upon the half-unblinded results by the number crunchers that monitor progress) bring the primary study to a quick close and perhaps prepare to roll out the more than sufficiently proven treatment to all participants, for equal benefit from this point on. And now monitor for Adverse Events on both "early" and "late" treatment groups. (It might not benefit those who are "late", compared to the initial enrollment criteria, it might actually show greater improvement to them or it could even exibit a surge of unexpected AEs from those who have been on longer-term dosage regimes; that all still needs teasing out from the stats.)

- Probably, in such a case, the patients (and blinded doctors) are only told that the study phase is over, not whether they are now necessarily being switched treatments, for continued double-blindedness. Once the study is truly finished, it would depend upon what the participant actually signed up for as to whether they (or their next of kin) ever learn the historic details of their participation.

- Conversely, significant AEs (by frequency or severity) that are identified as cropping up worse in the test treatment (vs placebo or in studies vs whatever prior treatment they are comparing against) should result in early ending and all those being changed to already accepted treatments.

- (But, for the latter, it could also just initially be a pause. To review the circumstances and determine relevent details behind the bare data. Such as the unexpectedly recorded death in a small nasal-spray trial being 'just' from being a passenger in a car accident, unlikely to have any connection with which cohort the participant was in – absent of a reported spate of other unusual AEs that indicated hightened tendencies to dangerous physical impulses, anyway.)

- The study design should have levels of significance that the core stats team (unblinded as far as "Patients X, Y, Z took the active treatment") will raise escalating concerns about continuing in the face of the more convincing or unconvincing results, even if the AE discrepancy is not as clear (or, in some cases, expected) as actual death. Like raised/lowered levels of reported bedsores, etc. With viagra being the obvious "secondary side-effect" examplar, detected as useful beyond the intended scope of the initial studies. 172.71.242.139 12:07, 19 January 2023 (UTC)

I'd sort of assume a placebo IRB would approve or deny projects randomly, where as a real one would "work" and actually analyse the projects being proposed. You could use this to see if the IRB is more ethical than a placebo, which you'd seriously hope. There'd obviously be a whole conversation on what constitutes more ethical, but you could prove that experimentally with a trial involving real and placebo philosophy and ethics departments 172.70.250.245 09:29, 19 January 2023 (UTC)

Should we be so quick to dismiss their results as poor study design, or a statistical blip? Isn't it possible that they have detected a real world phenomenon - that the particular sub-group in question is more susceptible to the placebo effect - and that this therefore needs controlling for in the real treatment trial? 172.70.162.56 15:10, 19 January 2023 (UTC)

Fun with ChatGPT

Prompt 1

Read the following XKCD comic strip transcript. Classify the roles of the characters (occupation). Explain the punchline. Explain the concepts of double-blind studies, the placebo effect, appropriate statistical significance, p-hacking and ethical considerations in medical research, and how they are portrayed in the comic strip.

[Cueball stands in front of a poster holding a pointer. The poster shows a scatter plot with four points and error bars, with one data point labeled "Subgroup" is marked with an asterisk and is placed somewhat higher up than the other three points.] Cueball: However, we see clear evidence that the treatment is more effective than the placebo for some subgroups. Off-panel voice: Thank you. Off-panel voice: However, we can now reveal that the London team was studying the real treatment. Both groups in your study got a placebo. Cueball: Aw, maaan... [Caption below panel] Researchers hate it when you do placebo controlled trials of their methodology.

Response 1

The characters in this comic strip are researchers.

The punchline of the comic strip is that the researcher (Cueball) was presenting data that seemed to show that a treatment was effective, but it was revealed that both groups in the study actually received a placebo, and the researcher did not realize it.

Double-blind studies are a type of research design where neither the participants nor the researchers know which participants are receiving the treatment or the placebo. This is done to prevent bias in the results.

The placebo effect is a phenomenon where a person's condition improves after receiving a placebo, which is a treatment that has no active ingredient. This effect can occur because the person believes they are receiving a real treatment.

Appropriate statistical significance is a measure of how likely it is that a result is due to chance. A commonly used threshold for statistical significance is a p-value of less than 0.05, which means that there is less than a 5% chance that the results are due to chance.

P-hacking refers to the practice of manipulating data or analysis in order to achieve a desired level of statistical significance.

Ethical considerations in medical research include ensuring that the rights and well-being of participants are protected and that the research is conducted in an honest and transparent manner.

The comic strip portrays the researcher's frustration when their methodology is tested by other researcher using a placebo controlled trial, and their results are not significant. It also highlights the importance of double-blind studies and appropriate statistical significance in research, as well as the dangers of p-hacking and the importance of ethical considerations in medical research.

Prompt 2

Take on the role of the researcher from the comic strip. Make a follow-up comic strip abut another research project this researcher undertakes. Come up with a funny and surprising, moderately nerdy punchline in XKCD style.

Response 2

[Cueball is standing in front of a poster holding a pointer. The poster shows a bar graph with two bars, one labeled "Treatment" and one labeled "Placebo". Both bars are the same height.] Cueball: Our latest study on the effectiveness of a new drug shows no significant difference between the treatment and the placebo. Off-panel voice: But wait, there's more! Off-panel voice: We have just discovered that both groups were accidentally given the same dosage of the drug. Cueball: (groans) I guess we'll have to redo the study with the correct dosages. [Caption below panel] Researchers hate it when you do a dosage controlled trials of their methodology.

In this follow-up comic strip, the researcher (Cueball) is presenting the results of a study on a new drug, and it is revealed that the study was flawed because both the treatment group and the placebo group received the same dosage of the drug, thus not allowing the researcher to determine the effectiveness of the drug. The punchline is that researchers hate it when you do a dosage controlled trial of their methodology, highlighting the importance of proper research design and execution.

The Simpsons did it before

Nope, for once NOT The Simpsons. A German SF TV classic:

https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Das_Blaue_Palais#Die_einzelnen_Folgen (Nr. 4, "Unsterblichkeit" - "Immortality")

Spoiler (as if anyone cares): Some mad scientist invented immortality (but only in the sense of "not aging", which is relevant, see below). The treatment is now tested in a placebo/true stuff split experiment, with the foreseeable effect that the "immortal" ones now are afraid of literally everything. (If you die anyway, you might as well smoke, drive a car, start a war, etc. pp.) Until it is revealed that another group interfered and, fearing the ethical consequences (the mad scientist didn't care about), substituted everything for placebo.

But what if researchers did actually go through this?

I can't help but wonder what if researchers did have to go through this. Fephisto (talk) 16:46, 19 January 2023 (UTC)

- I've heard of newly employed team of 'fresh' statiticians being 'broken in' on a fully placebo study (no actual patients, but looks like a regular one and may have some deliberate features added to it to make it interesting but not actually worrying) to see what they'd be actually like in the deep end (without them drowning themselves or anybody else, if they panic). But it's not as usual as each just individually serving in an assistive role/'apprenticeship'.

- I think it might have been a make-work thing, too, as they were hired for a project that was delayed, and it seemed easier to concoct a 'training scenario' than distribute them around the other groups (or let them go, again, for the duration) until they needed to be hauled back together to work with the main lead (who had plenty of other things too keep themselves busy, even after generating the simulated data-run they'd be trickle-fed).

- Not sure what they thought about the ethics of it, but as it affected nobody except themselves (and they were still earning the promised wages)... 172.70.85.46 17:51, 19 January 2023 (UTC)

Add comment

Add comment