3117: Replication Crisis

| Replication Crisis |

Title text: Maybe encouraging the publication of null results isn't enough--maybe we need a journal devoted to publishing results the study authors find personally annoying. |

Explanation

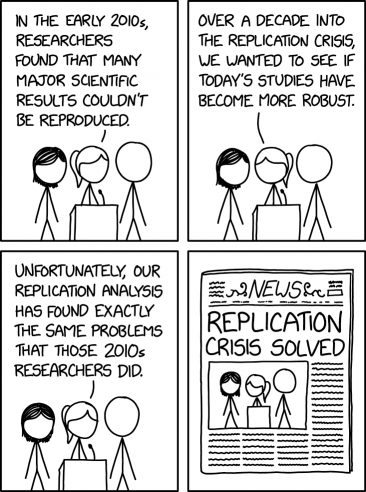

The replication crisis in science refers to the existence of a large number of published scientific results that others are unable to reproduce. One aspect of the scientific method is the replication of results, so the failure to replicate some results casts doubt on the validity of the results and scientific knowledge built on them. Research into the replication crisis itself has been done, with a number of studies being redone and the results compared with the original studies. In this comic, a research team is looking to see if the situation has improved and end up "reproducing" the same results of the early reproduction crisis papers.

The joke is about reproducing a paper about being unable to reproduce papers, while both papers show there is general issue with reproducibility, in this narrow case the scientists were able to reproduce an earlier result, hence the "solved" newspaper headline.

There is a further possible jab: the replication crisis has indeed been "solved", in that the paper authors have shown that the same problems crop up even when scientists are aware of the issue. The "solution" is that the problems persist whether or not the scientists are aware of the replication crisis, so one could simply do science as if the crisis did not happen. This would be not so much a 'solution' as a counsel of despair. 1574: Trouble for Science explores an issue similar to this comic's.

The title text refers to one previously suggested remedy when the replication crisis was first being dealt with — encouraging the publication of null results to counteract publication bias. However, because there is still a replication crisis it didn't solve the problem. The joke is that researchers, being human, are often tempted not to publish results if, for example, the results are not what they were expecting, opposed to a hypothesis they've spoken in favor of, likely to hurt their careers or embarrass them, confusing or difficult for them to explain, or aesthetically or in some other way displeasing to the researcher or their funder. Similarly to these actual efforts to counteract publication bias, this proposed measure extends this idea, albeit in a way that might sound silly.

Transcript

- [Megan, Ponytail, and Cueball are standing at a lectern. Ponytail is talking into the microphone.]

- Ponytail: In the early 2010s, researchers found that many major scientific results couldn't be reproduced.

- [Ponytail turns her head slightly to look around the room.]

- Ponytail: Over a decade into the replication crisis, we wanted to see if today's studies have become more robust.

- [Ponytail looks back at the original place she was looking]

- Ponytail: Unfortunately, our replication analysis has found exactly the same problems that those 2010s researchers did.

- [This panel shows a newspaper, with title "NEWS" surrounded by flourishes. There is a photo of the panel #2 without the text. There is much illegible text around the picture. The headline reads:]

- REPLICATION CRISIS SOLVED

Discussion

I believe the current explanation is a bit missing the point. It's supposed to mean that the authors shown in the comic failed to reproduce the result of the papers claiming that there are replication crisis, and therefore the original claim that there is a replication crisis going on is unfounded (since the papers claiming it cannot be replicated), and comically the headline in the last panel takes this to the next level by saying that this means there was no replication crisis to begin with. Justhalf (talk) 00:57, 19 July 2025 (UTC)

- I favor the current explanation's interpretation. "Today's studies", I think, refers to 2025 primary research papers across fields of science, and the team finds issues with their reproducibility similar to those found with 2015 primary research papers. I argue that the headline appropriate for "falsifying the replication crisis" would be REPLICATION CRISIS DEBUNKED, not CRISIS SOLVED; the latter tacitly accepts the finding of a replication crisis. I argue further that the demons responsible for the replication crisis are legion, and include the sheer mass and rapid worldwide growth of 'the literature', the 'publish or perish' demands of employers and funders especially given the inadequate money and time granted by funders (before the currently unfolding catastrophe), the rules of (usually volunteer) print-journal editors desperate to save money and space, the collapse under multiple pressures of peer review, the devolution of most actual work to the least paid and least experienced, the disastrous consequences of replacing integrity with propaganda ("don't be such a scientist"), yada. Issues that won't be addressed by publication of null results (oh goody, yet another predatory for-profit journal opportunity!) or annoying results, even if that idea does stimulate a wry chuckle on first reading. Once upon a time, there was a Journal of Irreproducible Results. "So what happened to it?" "That's what they all are now." 2605:59C8:160:DB08:C1B3:77CD:F0E3:3391 02:59, 19 July 2025 (UTC)

- I agree with the interpretation of Justhalf since it is simpler and more direct to the punchline than what is written in the explanation. Here's the joke: 1. in the 2010's a study showed there were too many research results that could not be replicated. 2. in 2025 another study looking at current research results, also found that many could not be replicated. 3. This second study confirms the first study thereby replicating their results, 4. the newspaper then announces "replication crisis solved" basing that on the fact that the second paper replicated the first one. Of course the newspaper got it wrong, because simply replicating one study, doesn't solve the problem that all the other studies were never replicated. That's the joke. It's very simple. please don't over think it and make it more complicated Rtanenbaum (talk) 20:06, 19 July 2025 (UTC)

- This also makes fun of the tendency of newspapers to sensationalize the result of a single study (in this case, the replication of the earlier study on non-reproducible results). This is why we often see things flip-flopping -- one time they'll say that wine is bad for you, a year later they'll say that it's good for you, and so on. Barmar (talk) 01:47, 20 July 2025 (UTC)

- I always prefer a self-referential explanation :-) BTW, we DO have a category Self-reference, does it encompass both in-universe (like here) and ex-universe (the comic itself is self-ref)?

This explanation is very convoluted and (IMHO), mostly wrong (and partially OK). I do not agree with Justhalt's interpretation, but I DO agree with Rtanenbaum's one (who says that they agree with Justhalt's! What!?). Here's my take in slow motion:

- 1. In 2010s, researchers reported some issues in science.

- 2. One decade later, the team in the panel wanted to see if these issues have improved over time.

- 3. The team in the panel replicated the exact same issues as the 2010s teams. So the issues haven't improved at all, but...

- 4. ... the team in the panel did replicate the 2010s' teams work exactly.