2225: Voting Referendum

| Voting Referendum |

Title text: The weirdest quirk of the Borda count is that Jean-Charles de Borda automatically gets one point; luckily this has no consequences except in cases of extremely low turnout. |

Explanation[edit]

The day before this comic's publication was an election day throughout the United States, primarily for local and state issues (normal elections for federal offices of the President, Senate, and House of Representatives are always in even years). The topic of today's comic highlights many different methods for conducting elections and counting votes. While elections are primarily used to allow voters to select from candidates for public offices, election ballots also frequently present questions for voters to directly voice their support or opposition to some change in a process or law - commonly called a referendum. The comic depicts an election ballot referendum for voters to select the method to be used in future elections. While the referendum is asking voters to select a method from a long list of methods, a referendum is usually presented as a specific proposal which requires a simple Yes or No vote.

As an example, the ballot in New York City included a referendum (which passed) on whether to use a different method, ranked choice voting (another name for instant-runoff voting as described below).

A common issue with such referenda is what method to use to conduct the referendum itself. Here, the method of marking each choice on the ballot reflects the marking method which would be used if it were the winner. Moreover, each item is listed in a way which is suggestive of what it means (e.g., "First past the post" is the first one, "Top-two" is among the top two, and "Multiple non-transferable vote" is selected among numerous other ones). A few of the methods allow for multiple winners, which can often be good when electing councils and representatives, but it is unclear what it would mean to have several of these voting methods all win.

The aim of political elections in first-past-the-post is to determine which of the candidates standing for election is most preferred by the most voters. In a simple two-person contest, this process is quite effective, since whichever candidate receives the most votes will be the one that the majority of voters prefer. This system works well for simple cases, but for elections with more than two candidates this system may result in a candidate being elected who less than 50% of the voters would prefer.

For example, in a contest with three candidates, A, B and C, in which candidate A receives 43% of the vote, candidate B 38%, and candidate C 19%, candidate A will be elected, even though some of the voters who chose candidate C might have preferred candidate B as their second choice instead of candidate A, leading to a result which pleases less than half of the population. For example, the above distribution of votes happened in the 2000 United States presidential election in Florida, where George W. Bush beat Al Gore by less than 1000 votes largely because of the third-party candidacy Ralph Nader, whose 100,000 voters would mostly have otherwise gone to Gore.

Additionally, in election of multiple candidates across a country (or region etc.), first past the post does not lead to a distribution of elected representatives proportional to the total number of votes, only electing the lead candidate in each case. For example, imagine a country with 100 representatives to be elected, with each seat having the same distribution as described in the example above. Under first past the post, 100 representatives will be elected representing party A, and none for party B or C.

Despite these drawbacks, First Past the Post voting continues to be used for political elections in many countries including the US and UK, which historically have both had two main parties receiving the majority of votes. The First Past the Post system has received much criticism, particularly from smaller parties who may lose out; however, supporters promote the simplicity of the system compared to other methods.

This system is shown with a radio button, the classic computer metaphor for being allowed one choice out of a set.

This method is used in California and Washington to select candidates for the US House of Representatives. In most states' primary-election systems, each party votes separately to select one candidate to continue to a first-past-the-post general election ballot. In these two states, on the other hand, candidates from all parties, as well as "independent" candidates from no party, run in a single race, and the top two finishers then contest the general election, even if both are from the same party (a common occurrence in heavily-Democratic California), and even if one candidate has a clear majority of the vote. (In an older version, a majority winner in the primary was immediately declared elected. This was held to be in violation of federal law, by effectively setting an "election day" before the national Election Day in November.) This is a form of the two-round system, a system for selecting elected officials most notably used to elect the President of France

This system is almost identical to the top-two primary, but with two differences. First, the open-to-all ballot is held on the national Election Day, instead of on the state's primary day. (This avoids the conflict with Federal law described above.) Also, the second round of the election is not held if one candidate has a clear majority (more than 50%) of the votes in the first round. Like the top-two primary and the first-past-the post system, the comic represents this system with a radio button, except this one has been marked, indicating the vote.

In cumulative voting, voters get as many votes as there are seats to be filled, and may distribute them as they choose. This system's most common use is in selecting corporate boards of directors. It is also used in some areas to allow a minority bloc within an electorate to elect some of its preferred candidates without imposing a system of separate districts.

The comic illustrates this with multiple radio buttons, each row representing an option/candidate and each (implied) column one vote. On the ballot the first 2 radio buttons are marked, as they are each the only radio buttons in their column and cannot be unmarked.

In this system, each candidate is listed as a yes/no choice, where the voters can choose which candidates they approve of winning the election, and which ones they do not approve of. The winner of the election is the candidate with the highest approval rate.

This type of voting system can be used as a vetting process to filter out undesirable candidates before the final vote; for example, the United Nations uses a series of "straw polls" to filter out candidates for the Secretary General before the Security Council makes a final vote. In 2018, Fargo, North Dakota switched to using approval voting to elect local politicians, making it the only jurisdiction in the United States to use this system. In the xkcd ballot, the approval option is presented as a checkbox, where a check in the box is "approve" or an empty box is "disapprove". Checkboxes are distinct from radio buttons in that several can be marked in the same field, and can also be unmarked without marking another.

This system for electing multiple members to a ruling body is also known as plurality-at-large voting or block vote. It is commonly used in the US for city council elections, and simply limits the number of votes per voter to the number of winners. It allows a cohesive plurality of the electorate to claim all of the seats, denying other voters any representation whatsoever.

In 2019, the Justice Department required Eastpointe, Michigan to run at least the next two elections via single transferable vote because their existing plurality-at-large system was disenfranchising black citizens.

This system is also shown as a checkbox, as each candidate gets either 0 or 1 votes from each voter.

In this system, people vote for all the candidates, or perhaps their favorite three, but assign different preferences to each candidate they vote for, as in 1 for their first choice, 2 for the second, 3 for their third, etc. If at least 50% of voters vote for a candidate as their first choice, that candidate wins. If not, the person with the least votes gets eliminated, and anyone who voted for that person has their next (slightly less favorable) choice automatically move up a rung. The 50% mark is again checked, and if there is no winner, another lowest-voted candidate is eliminated. Eventually one candidate will emerge victorious. The advantages of this system are that there is rarely a need to have another election if things are close (the information is already there to "instantly" recalculate the vote based on additional voter preferences), and "spoiler" candidates only cause problems when they become competitive. And as Arrow's impossibility theorem shows, as with all ranking methods, sometimes voters can hurt a candidate by ranking them more favorably.

On this weird xkcd ballot, we see this type of ranking between this type of voting (Instant runoff voting) and the two that follow (Single transferable vote and Borda count), all of which allow multiple ranked votes. It appears that between these three, Randall has voted for Single transferable vote as his top choice, Borda count for his second choice, with Instant runoff voting as his third choice.

This system extends the instant runoff to multiple-winner elections. Specifically, the election threshold is set not at 50%, but at 100%/(k+1) where k candidates will win (in other words, just high enough to prevent more candidates from reaching it than there are seats). The bottom candidates are eliminated as in instant-runoff and their votes redistributed. In addition, if a candidate wins with more than enough votes, the extra votes (either a fraction of each vote, or some subset of the ballots) are also redistributed. This procedure continues until the requisite number of winners is reached.

Each ballot is counted as 1 point for the last choice, 2 for next-to-last, and so on up to n for the first choice among n candidates. The highest point-earner(s) win. This system may also be calculated as 1 point for first choice, 2 for second, etc., with the lowest total winning; this variant, called the "cross-country vote" (due to its resemblance to the scoring system of the sport of cross-country running), is used by the NCAA's various selection committee as one step in choosing championship tournament fields.

The title text refers to the inventor of the Borda count, Jean-Charles de Borda (for whom it is named), implying that the use of the system implies the inclusion of a ballot in which he gets one point in the counting. This "1 point" would be quickly drowned out by any sensible quantity of actual votes. This also humorously suggests that if no one were to vote at all, Borda would win by default, which is apparently a bad thing, possibly because Borda has been dead since 1799 and thus shouldn't be able to serve.[citation needed]

For each candidate, the voter selects a value within a fixed range (the xkcd voter sees this choice presented as a slider) for each candidate, independent of the values given to other candidates. The highest total wins. (If the range is restricted to two values, this becomes the approval system.)

The punchline for the comic is that the whole referendum is a chicken-and-egg problem: in order to accomplish the purpose of a referendum, one needs to know how the votes will be translated into a result, but in this case, determining that rule is the purpose of the referendum. Additionally this xkcd demonstrates one of the mechanisms that makes it hard to change the currently-used voting system in any state: Each voting system in fact votes for itself as the ones who are able to decide upon the voting system being in use have been elected using the current voting system and therefore are likely to profit from it.

Transcript[edit]

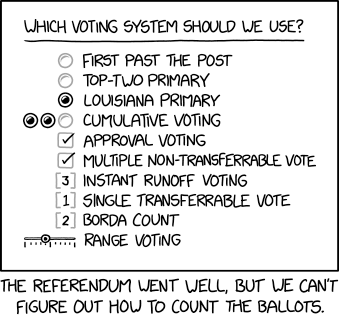

- [A voting ballot is shown with an underlined header and 10 different options below with different boxes/buttons next to each choice. Some are empty, some are marked/checked or numbered.]

- Which voting system should we use?

- [Empty radio button]: First past the post

- [Empty radio button]: Top-two primary

- [Filled radio button]: Louisiana primary

- [Three radio buttons in a row, first two filled]: Cumulative voting

- [Checked box]: Approval voting

- [Checked box]: Multiple non-transferrable vote

- [Box marked]: 3: Instant runoff voting

- [box marked]: 1: Single transferrable vote

- [box marked]: 2: Borda count

- [Slider with value slightly below half]: Range voting

- [Caption below the panel:]

- The referendum went well, but we can't figure out how to count the ballots.

Discussion

OK, I just created a massive edit conflict, I see. Will move my content into the appropriate parts of the template already in place. Silverpie (talk) 20:37, 6 November 2019 (UTC)

If there is disagreement about which edits are better, we should vote on it. Which system of voting would be best for that? -boB (talk) 21:08, 6 November 2019 (UTC)

Someone (IP-User) just added the following:

Additionally, in election of multiple candidates across a country (or region etc.), first past the post does not lead to a distribution of elected representatives proportional to the total number of votes, only electing the lead candidate in each case. For example, imagine a country with 100 representatives to be elected, with each seat having the same distribution as described in the example above. Under first past the post, 100 representatives will be elected representing part A, and none for party B or C.

Unless there is some example where this is used (multiple seats given only to the winner of a first past the post) I'd vote for removing this statement. As I do not know all (or even many) democratic systems worldwide, I am not sure if it might be relevant somewhere. --Lupo (talk) 13:58, 7 November 2019 (UTC)

- That's how the US Electoral College works: in each state, all elector seats go to the party that obtained the majority of votes.162.158.234.94 14:53, 7 November 2019 (UTC)

- Really? I knew that the "electoral college" was fucked up, but I was not aware, that the US system is this bad... --Lupo (talk) 15:06, 7 November 2019 (UTC)

- The US system is the most broken system in a democracy... See CGP Greys videos on first past the post and general playlist of Politics in America. --Kynde (talk) 21:05, 7 November 2019 (UTC)

- Sort of – that's how most states choose to allocate their electors (who don't actually *have* to vote for the candidate they're pledged to, but that's a whole other story). Some states, like Maine, do it proportionally instead. See the wikipedia section on alternative methods of choosing electors. BobbingPebble (talk) 14:27, 9 November 2019 (UTC)

- Really? I knew that the "electoral college" was fucked up, but I was not aware, that the US system is this bad... --Lupo (talk) 15:06, 7 November 2019 (UTC)

Problem of selecting the method of voting was already considered in Polish comedy The Cruise (Pol. Rejs). "But what voting system can be used to select the method of voting?" Tkopec (talk) 09:34, 8 November 2019 (UTC)

- Also a BBC Radio sketch show (whose title escapes me right now, sorry) had a whole skit about (randomly) choosing something by going through all kinds of 'decision' methods with a sequence featuring things like "...but who rolls the dice?" / "We'll flip a coin for it" / "But whose coin do we flip?" / "We'll draw lots for it." / "But who draws first..?" with it wrapping round back to the first undecidable decision-method. But written better, naturally... ;) 141.101.98.208 19:06, 11 November 2019 (UTC)

- Louisiana Primary

I didn't know - WikiP: The so-called Louisiana primary is the common term for the Louisiana general election for local, state, and congressional offices.[1] On election day, all candidates for the same office appear together on the ballot, often including several candidates from each major party. The candidate who receives a simple majority is elected. If no candidate wins a simple majority in the first round, there is a runoff one month later between the top two candidates to determine the winner. This system is also used for United States Senate special elections in Mississippi and Texas, and all special elections for partisan offices in Georgia.[2]Afbach (talk)

This is also known as a "Jungle Primary" and is also done in Washington state and California. 108.162.219.58 20:00, 6 November 2019 (UTC)

I had to resolve an editing conflict in the first paragraph with another editor, but please feel free to further resolve our differing edits. Ianrbibtitlht (talk) 20:26, 6 November 2019 (UTC)

- Single Transferable Vote

The text says "100%/(k+1)". Surely this should be "100%/k + 1", or "100%/k, plus one person"? Say k is 4. The current text implies that only 20% is required, when it should be 25%, plus one person. John.Adriaan (talk) 01:55, 7 November 2019 (UTC)

- Setting a quota at 25% plus one person would only allow 3 people to be elected, as once that happens there would be less than 25% of the vote left to count which wouldn't be enough to elect anyone else. Setting the quota at 100%/(k+1) means that k people can be elected before the remaining vote isn't enough to elect anyone else (setting the quota at exactly 100%/k, by the way, has also been used and is known as the Hare quota). Arcorann (talk) 02:21, 7 November 2019 (UTC)

- Say k is 4. Then 100%/(4+1) = 20%. So, yes, it's possible that you could end up with 5 people all getting exactly 20%. But a perfect 5-way tie like that would be extremely unlikely. Other than that very improbable result, only 4 people could get elected, as is desired. Imagine, for example, one person gets juuust over 20% of the vote. Even just that little bit over means there's less than 80% of the vote left for the other four. Which means only 3 of the remaining 4 people could get over the 20% threshold.

- Of course the correct formula should be "100%/(k+1)+1". -- Hkmaly (talk) 04:23, 7 November 2019 (UTC)

- Which could result in no-one being elected if, say, 5 candidates each get exactly 20% of the vote. 162.158.158.127 22:17, 7 November 2019 (UTC)

- Which would be in some sense fair, as noone is more favourable to the voters than the other 4 candidates, while there is only 4 seats... So there needs to be a second referendum or some other measure for that case. --Lupo (talk) 06:59, 8 November 2019 (UTC)

- In that case the system would handle the situation the same way it handles ties when candidates have smaller numbers of votes (every system needs to handle ties somehow, after all). Arcorann (talk) 09:23, 8 November 2019 (UTC)

- Which could result in no-one being elected if, say, 5 candidates each get exactly 20% of the vote. 162.158.158.127 22:17, 7 November 2019 (UTC)

- Of course the correct formula should be "100%/(k+1)+1". -- Hkmaly (talk) 04:23, 7 November 2019 (UTC)

I just came here to see if there was a discussion on which system actually should be selected, according to the ballot displayed. I'm sadly disappointed that there isn't one, lol. 172.69.68.219 17:25, 7 November 2019 (UTC) Sam @Sam, just for you then: According to the ballot displayed, I, as the Commissioner of XKCD Voting Comic voting, and retired OTTer, hereby remind you that it isn't what people vote for but who counts the votes. I've counted, and the winning system is [redacted] Cellocgw (talk) 15:22, 8 November 2019 (UTC)

Can we hold an election for who gets to give me all their money, use the Borda count, and then not vote at all? So he'd pay me (if he's still alive of course). SilverMagpie (talk) 20:16, 8 November 2019 (UTC)

Assume that counting votes under the best election method will select the best election method. IOW, the best election method will select itself. So, if there happens to be exactly one election method that chooses itself, then the problem is solved. 108.162.221.89 02:09, 9 November 2019 (UTC)

TIL that I independently reinvented the Borda count method. One way that I use it is in a spreadsheet that ranks my cards in the Animation Throwdown online card game. I hope that Borda's heirs aren't royalty-happy. These Are Not The Comments You Are Looking For (talk) 20:48, 10 November 2019 (UTC)

With FPTP, which was the obvious go-to-method, we always elected a boy as class-speaker, even though we had more girls in our class, back in school. While there was usually just one boy interested, who got himself up as a candidate, he got all of the boys votes, while the girls votes where usually split across 2 or 3 female candidates they fielded. So even though the girls were more engaged in school-politics, they never provided the class speaker... --Lupo (talk) 15:41, 13 November 2019 (UTC)

I know nobody has commented on this article for over 2⅓ years, but I was reading the explanation just now for the "First past the post" section, and something in it bothers me. It says "For example, [if] ... A receives 43%, ... B 38%, and ... C 19%, candidate A will be elected" and then later says "the above distribution of votes happened in the 2000 United States presidential election in Florida..."

So... did it used to actually have the voting percentage distributions for Bush, Gore, and Nader (which would be, respectively, 48.85%, 48.84%, and 1.64% of total votes cast - with an additional 0.68% voting for others - or, alternatively (but less straightforward), out of all the votes cast for those three, 49.18%, 49.17%, and 1.65%) Mathmannix (talk) 19:27, 23 March 2022 (UTC)