1047: Approximations

| Approximations |

| ↓ Skip to explanation ↓ |

Title text: Two tips: 1) 8675309 is not just prime, it's a twin prime, and 2) if you ever find yourself raising log(anything)^e or taking the pi-th root of anything, set down the marker and back away from the whiteboard; something has gone horribly wrong. |

Explanation[edit]

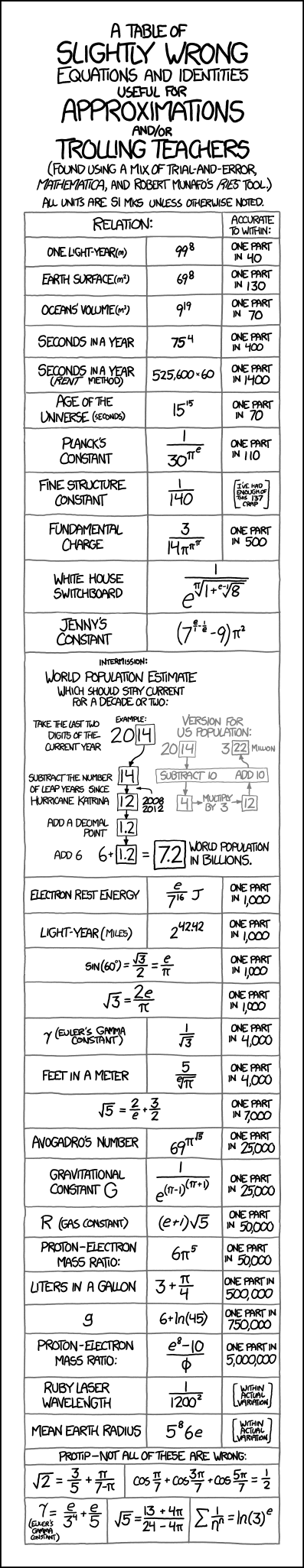

This comic lists some approximations for numbers, most of them mathematical and physical constants, but some of them jokes and cultural references.

Approximations like these are sometimes used as mnemonics by mathematicians and physicists, though most of Randall's approximations are too convoluted to be useful as mnemonics. Perhaps the best known mnemonic approximation (though not used here by Randall) is that "π is approximately equal to 22/7". Randall does mention (and mock) the common mnemonic among physicists that the fine structure constant is approximately 1/137. Although Randall gives approximations for the number of seconds in a year, he does not mention the common physicists' mnemonic that it is "π × 107", though he later added a statement to the top of the comic page addressing this point.

At the bottom of the comic are expressions involving transcendental numbers (namely π and e) that are tantalizingly close to being exactly true but are not (indeed, they cannot be, due to the nature of transcendental numbers). Such near-equations were previously discussed in 217: e to the pi Minus pi. One of the entries, though, is a "red herring" that is exactly true.

Randall says he compiled this table through "a mix of trial-and-error, Mathematica, and Robert Munafo's Ries tool." "Ries" is a "reverse calculator" that forms equations matching a given number.

The world population estimate for 2025 is still somewhat accurate. The estimate is 8.0 billion, and the population listed at the website census.gov is roughly the same. The current value can be found here: United States Census Bureau - U.S. and World Population Clock. Nevertheless, there are other numbers listed by different sources.

The first part of the title text notes that "Jenny's constant," which is actually a telephone number referenced in Tommy Tutone's 1982 song 867-5309/Jenny, is not only prime but a twin prime because 8675311 is also a prime. Twin primes have always been a subject of interest, because they are comparatively rare, and because it is not yet known whether there are infinitely many of them. Twin primes were also referenced in 1310: Goldbach Conjectures.

The second part of the title text makes fun of the unusual mathematical operations contained in the comic. π is a useful number in many contexts, but it doesn't usually occur anywhere in an exponent. Even when it does, such as with complex numbers, taking the πth root is rarely helpful. A rare exception is an identity for the pi-th root of 4 discovered by Bill Gosper. Similarly, e typically appears in the base of a power (forming the exponential function), not in the exponent. (This is later referenced in Lethal Neutrinos).

In 217: e to the pi Minus pi and 3023: The Maritime Approximation Randall gives other approximations based on numerical coincidences.

Equations[edit]

| Thing to be approximated: | Formula proposed | Resulting approximate value | Correct value | Discussion | Error |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| One light year (meters) | 998 | 9,227,446,944,279,201 | 9,460,730,472,580,800 (exact) | Based on 365.25 days per year (see below). 998 and 698 are sexual references. | 2.3328353 × 1014 |

| Earth's surface (m2) | 698 | 513,798,374,428,641 | 5.10072 × 1014 | 998 and 698 are sexual references. | 3.7263744 × 1012 |

| Oceans' volume (m3) | 919 | 1,350,851,717,672,992,089 | 1.332 × 1018 | ||

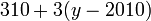

| Seconds in a year | 754 | 31,640,625 | 31,557,600 (Julian calendar), 31,556,952 (Gregorian calendar) | After this comic was released Randall got many responses by viewers. So he did add this statement to the top of the comic page:

"Lots of emails mention the physicist favorite, 1 year = pi × 107 seconds. 754 is a hair more accurate, but it's hard to top 3,141,592's elegance." π × 107 is nearly equal to 31,415,926.536, and 754 is exactly 31,640,625. Randall's elegance belongs to the number π, but it should be multiplied by the factor of ten. Using the traditional definitions that a second is 1/60 of a minute, a minute is 1/60 of an hour, and an hour is 1/24 of a day, a 365-day common year is exactly 31,536,000 seconds (the "Rent method" approximation) and the 366-day leap year is 31,622,400 seconds. Until the calendar was reformed by Pope Gregory, there was one leap year in every four years, making the average year 365.25 days, or 31,557,600 seconds. On the current calendar system, there are only 97 leap years in every 400 years, making the average year 365.2425 days, or 31,556,952 seconds. In technical usage, a "second" is now defined based on physical constants, even though the length of a day varies inversely with the changing angular velocity of the earth. To keep the official time synchronized with the rotation of the earth, a "leap second" is occasionally added, resulting in a slightly longer year. | |

| Seconds in a year (Rent method) | 525,600 × 60 | 31,536,000 | 31,557,600 (Julian calendar), 31,556,952 (Gregorian calendar) | "Rent Method" refers to the song "Seasons of Love" from the musical Rent. The song asks, "How do you measure a year?" One line says "525,600 minutes" while most of the rest of the song suggests the best way to measure a year is moments shared with a loved one. This method for remembering how many seconds are in a year was also referenced in Short Answer Section II, where Cueball gets the song stuck in his head whilst calculating how many counterfeit bills he can print in a year. | |

| Age of the universe (seconds) | 1515 | 437,893,890,380,859,375 | (4.354 ± 0.012) × 1017 (best estimate; exact value unknown) | This one will slowly get more accurate as the universe ages. | |

| Planck's constant |

|

6.6849901410 × 10−34 | 6.62606957 × 10−34 | Informally, the Planck constant is the smallest action possible in quantum mechanics. | |

| Fine structure constant |

|

0.00714285 | 0.0072973525664 (accepted value as of 2014), close to 1/137 | The fine structure constant indicates the strength of electromagnetism. It is unitless and around 0.007297, close to 1/137. The joke here is that Randall chose to write 140 as the denominator, when 137 is much closer to reality and just as many digits (although 137 is a less "round" number than 140, and Randall writes in the table that he's "had enough" of it). At one point the fine structure constant was believed to be exactly the reciprocal of 137, and many people have tried to find a simple formula explaining this (with a pinch of numerology thrown in at times), including the infamous Sir Arthur "Adding-One" Eddington who argued very strenuously that the fine structure constant "should" be 1/136 when that was what the best measurements suggested, and then argued just as strenuously for 1/137 a few years later as measurements improved. | |

| Fundamental charge |

|

1.59895121062716 × 10−19 | 1.602176634 × 10−19 | This is the charge of the proton, symbolized e for electron (whose charge is actually −e. You can blame Benjamin Franklin for that.) | |

| Telephone number for the White House switchboard | ![\frac {1} {e^ {\sqrt[\pi] {1 + \sqrt[e-1] 8}} }](/wiki/images/math/d/9/7/d9765d35e4dfec660f7558e016b3ee5f.png)

|

0.2024561414932 | 202-456-1414 | ||

| Jenny's constant |

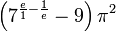

|

867.5309019 | 867-5309 | A telephone number referenced in Tommy Tutone's 1982 song 867-5309/Jenny. As mentioned in the title text, the number is not only prime but a twin prime because 8675311 is also a prime. | |

| World population estimate (billions) | Equivalent to

|

2005 — 6.5 2006 — 6.6 |

Grows by 75 million every year on average (100 million every year, except for a pause every leap-year). As of 2025, still more or less accurate. (8.0B) | ||

| U.S. population estimate (millions) | Equivalent to

|

2000 — 280 2001 — 283 |

Grows by 3 million each year. As of 2024 the actual number is ~10 million smaller. | ||

| Electron rest energy (joules) |

|

8.17948276564429 × 10−14 | 8.18710438 × 10−14 | ||

| Light year (miles) | 242.42 | 5,884,267,614,436.97 | 5,878,625,373,183.61 = 9,460,730,472,580,800 (meters in a light-year, by definition) / 1609.344 (meters in a mile) | 42 is, according to Douglas Adams' The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy, the answer to the Ultimate Question of Life, the Universe, and Everything. | |

|

|

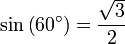

0.8652559794 | 0.8660254038 | ||

|

|

1.7305119589 | 1.7320508076 | Same as the above | |

| γ (Euler's gamma constant) |

|

0.5773502692 | 0.5772156649 | The Euler–Mascheroni constant (denoted γ) is a mysterious number describing the relationship between the harmonic series and the natural logarithm. | |

| Feet in a meter | ![\frac {5} {\sqrt[e]\pi}](/wiki/images/math/e/4/6/e468eee193d15e499b36ce29a20673ef.png)

|

3.2815481951 | 3.280839895 | Exactly 1/0.3048, as the international foot is defined as 0.3048 meters. | |

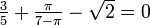

|

|

2.2357588823 | 2.2360679775 | ||

| Avogadro's number |

|

6.02191201246329 × 1023 | 6.02214129 × 1023 | Also called a mole for shorthand, Avogadro's number is (roughly) the number of individual atoms in 12 grams of pure carbon. Used in basically every application of chemistry. In 2019 the constant was redefined to 6.02214076 × 1023, making the Approximation slightly more correct. | |

| Gravitational constant G |

|

6.6736110685 × 10−11 | 6.67385 × 10−11 | The universal gravitational constant G is equal to Fr2/Mm, where F is the gravitational force between two objects, r is the distance between them, and M and m are their masses. | |

| R (gas constant) |

|

8.3143309279 | 8.3144622 | The gas constant relates energy to temperature in physics, as well as a gas's volume, pressure, temperature and molar amount (hence the name). | |

| Proton–electron mass ratio |

|

1836.1181087117 | 1836.15267246 | The proton-to-electron mass ratio is the ratio between the rest mass of the proton divided by the rest mass of the electron. | |

| Liters in a gallon |

|

3.7853981634 | 3.785411784 (exact) | A U.S. liquid gallon is defined by law as 231 cubic inches. The British imperial gallon would be about 20% larger (but the litre is the same thing as the US liter). | |

| g0 or gn | 6 + ln(45) | 9.8066624898 | 9.80665 | Standard gravity, or standard acceleration due to free fall is the nominal gravitational acceleration of an object in a vacuum near the surface of the Earth. It is defined by standard as 9.80665 m/s2, which is exactly 35.30394 km/h/s (about 32.174 ft/s2, or 21.937 mph/s). This value was established by the 3rd CGPM (1901, CR 70) and used to define the standard weight of an object as the product of its mass and this nominal acceleration. The acceleration of a body near the surface of the Earth is due to the combined effects of gravity and centrifugal acceleration from rotation of the Earth (but which is small enough to be neglected for most purposes); the total (the apparent gravity) is about 0.5 percent greater at the poles than at the equator.

Randall used a letter g without a suffix, which can also mean the local acceleration due to local gravity and centrifugal acceleration, which varies depending on one's position on Earth. | |

| Proton–electron mass ratio |

|

1836.1530151398 | 1836.15267246 | φ is the golden ratio, or  . It has many interesting geometrical properties. . It has many interesting geometrical properties.

| |

| Ruby laser wavelength (meters) |

|

6.9444 × 10−7 | ~6.943 × 10−7 | The ruby laser wavelength varies because "ruby" is not clearly defined. | |

| Mean Earth radius (meters) |

|

6,370,973.035 | 6,371,008.7 (IUGG definition) | The mean earth radius varies because there is not one single way to make a sphere out of the earth. Randall's value lies within the actual variation of Earth's radius. The International Union of Geodesy and Geophysics (IUGG) defines the mean radius as 2/3 of the equatorial radius (6,378,137.0 m) plus 1/3 of the polar radius (6,356,752.3 m). | |

|

|

1.4142200581 | 1.4142135624 | There are recurring math jokes along the lines of, " , but your calculator is probably not good enough to compute this correctly". See also 217: e to the pi Minus pi. , but your calculator is probably not good enough to compute this correctly". See also 217: e to the pi Minus pi.

| |

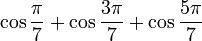

|

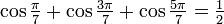

|

0.5 | 0.5 (exact) | This is the exactly correct equation referred to in the note, "Pro tip – Not all of these are wrong", as shown below and also here. If you're still confused, the functions use radians, not degrees: when an angular measure does not specify units, radians are the assumed default. | |

| γ (Euler's gamma constant) |

|

0.5772154006 | 0.5772156649 | The Euler–Mascheroni constant (denoted γ) is a mysterious number describing the relationship between the harmonic series and the natural logarithm. | |

|

|

2.2360678094 | 2.2360679775 | ||

|

|

1.2912987577 | 1.2912859971 |

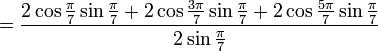

Proof[edit]

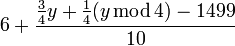

One of the "approximations" actually is precisely correct:  . Here is a proof:

. Here is a proof:

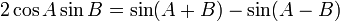

Multiplying by 1 (or by a nonzero number divided by itself) leaves the equation unchanged:

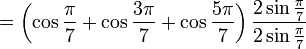

The  on the top of the fraction is multiplied through the original equation:

on the top of the fraction is multiplied through the original equation:

Use the trigonometric identity  on the second and third terms in the numerator:

on the second and third terms in the numerator:

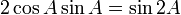

Use the trigonometric identity  on the first term in the numerator:

on the first term in the numerator:

Noting that  and that the sines of supplementary angles (angles that sum to π) are equal:

and that the sines of supplementary angles (angles that sum to π) are equal:

To better see why the equation is true, it is better to go to the complex plane. cos(2k pi/7) is the real part of the k-th 7-th root of unity, exp(2 k i pi/7). The seven 7-th roots of unity (for 0 <= k <= 6) sum up to zero, hence so do their real parts:

- 0 = cos(0 pi/7) + cos(2 pi/7) + cos(4 pi/7) + cos(6 pi/7) + cos(8 pi/7) + cos(10 pi/7) + cos(12 pi/7)

But one of these roots is just 1, and all other root go by pairs of conjugate roots, which have the same real part (alternatively, consider that cos(x) = cos(2 pi - x)):

- 0 = 1 + 2 (cos(2 pi/7) + cos(4 pi/7) + cos(6 pi/7))

Hence

- cos(2 pi/7) + cos(4 pi/7) + cos(6 pi/7) = - 1/2

which, because cos(x) = -cos(pi - x), can be rewritten as

- cos(5 pi/7) + cos(3 pi/7) + cos(pi/7) = 1/2

Q.E.D.

Transcript[edit]

- A table of slightly wrong equations and identities useful for approximations and/or trolling teachers.

- (Found using a mix of trial-and-error, Mathematica, and Robert Munafo's Ries tool.)

- All units are SI MKS unless otherwise noted.

Relation: Accurate to within: One light-year(m) 998 one part in 40 Earth Surface(m2) 698 one part in 130 Oceans' volume(m3) 919 one part in 70 Seconds in a year 754 one part in 400 Seconds in a year (Rent method) 525,600 x 60 one part in 1400 Age of the universe (seconds) 1515 one part in 70 Planck's constant 1/(30πe) one part in 110 Fine structure constant 1/140 [I've had enough of this 137 crap] Fundamental charge 3/(14 * πππ) one part in 500 White House Switchboard 1 / (eπ√(1 + (e-1)√8)) Jenny's Constant (7(e/1 - 1/e) - 9) * π2 Intermission:

World Population Estimate

which should stay current

for a decade or two:

Take the last two digits of the current year

Example: 20[14]

Subtract the number of leap years since hurricane Katrina

Example: 14 (minus 2008 and 2012) is 12

Add a decimal point

Example: 1.2

Add 6

Example: 6 + 1.2

7.2 = World population in billions.

Version for US population:Example: 20[14]

Subtract 10

Example: 4

Multiply by 3

Example: 12

Add 10

Example: 3[22] million

Electron rest energy e/716 J one part in 1000 Light-year(miles) 2(42.42) one part in 1000 sin(60°) = √3/2 = e/π one part in 1000 √3 = 2e/π one part in 1000 γ(Euler's gamma constant) 1/√3 one part in 4000 Feet in a meter 5/(e√π) one part in 4000 √5 = 2/e + 3/2 one part in 7000 Avogadro's number 69π√5 one part in 25,000 Gravitational constant G 1 / e(π - 1)(π + 1) one part in 25,000 R (gas constant) (e+1) √5 one part in 50,000 Proton-electron mass ratio 6*π5 one part in 50,000 Liters in a gallon 3 + π/4 one part in 500,000 g 6 + ln(45) one part in 750,000 Proton-electron mass ratio (e8 - 10) / ϕ one part in 5,000,000 Ruby laser wavelength 1 / (12002) [within actual variation] Mean Earth Radius (58)*6e [within actual variation] Protip - not all of these are wrong: √2 = 3/5 + π/(7-π) cos(π/7) + cos(3π/7) + cos(5π/7) = 1/2 γ(Euler's gamma constant) = e/34 + e/5 √5 = (13 + 4π) / (24 - 4π) Σ 1/nn = ln(3)e

Discussion

The US population estimate is now off by 7 million, although 2018 just started. Even so, in December 2017, it would have been 4 million off. 625571b7-aa66-4f98-ac5c-92464cfb4ed8 (talk) 00:54, 19 January 2018 (UTC)

- Off by 7 million out of 7-8 billion means that it's accurate to one part in 1,000. That's consistent with it's location in the chart -- next to other values that are accurate to 1 in 1,000. -- Redbelly98 (talk) (please sign your comments with ~~~~)

The world population estimate is still accurate to within .1 billion. 162.158.63.28 13:41, 5 May 2017 (UTC)

- Same here in 2024! Psychoticpotato (talk) 13:15, 28 May 2024 (UTC)

They're actually quite accurate. I've used these in calculations, and they seem to give close enough answers. Davidy22[talk] 14:03, 8 January 2013 (UTC)

I only see a use for the liters in a gallon one. The rest are for trolling or simple amusement. The cosine identity bit our math team in the butt at a competition. It was painful. --Quicksilver (talk) 05:27, 17 August 2013 (UTC)

Annoyingly this explanation does not cover 42 properly, it does not say that Douglas Adams got the number 42 from Lewis Carroll, who is more relevant to the page because he was a mathematician named Charles Lutwidge Dodgson. He was obsessed with the number forty-two. The original plate illustrations of Alice in Wonderland drawn by him numbered forty-two. Rule Forty-Two in Alice in Wonderland is "All persons more than a mile high to leave the court", There is also a Code of Honour in the preface of The Hunting of the Snark, an extremely long poem written by him when he was 42 years old, in which rule forty-two is "No one shall speak to the Man at the Helm". The queens in Alice Through the Looking Glass the White Queen announces her age as "one hundred and one, five months and a day", which - if the best possible date is assumed for the action of Through the Looking-Glass - gives a total of 37,044 days. With the further (textually unconfirmed) assumption that both Queens were born on the same day their combined age becomes 74,088 days, which is 42 x 42 x 42. --139.216.242.254 02:43, 29 August 2013 (UTC)

- This explanation covers 42 adequately, and would probably be made slightly worse if such information were added. The very widely known cultural reference is to Adams's interpretation, not Dodgson's original obsession. Adding it would be akin to introducing the MPLM into the explanation for the hijacking of Renaissance artists' names by the TMNT. I definitely concede that it does not cover 42 exhaustively, but I think it can be considered complete and in working order without such an addition. If it really irks you, be bold and add it! --Quicksilver (talk) 00:37, 30 August 2013 (UTC)

- Additionally, the Lewis Carroll idea is only one of several theories about where Douglas Adams got the number from. 162.158.158.87 20:47, 28 November 2019 (UTC)

"sqrt(2) is not even algebraic in the quotient field of Z[pi]" is not correct. Q is part of the quotient field of Z[pi] and sqrt(2) is algebraic of it. The needed facts are that pi is not algebraic, but the formula implies it is in Q(sqrt(2)). --DrMath 06:47, 7 September 2013 (UTC)

13/15 is a better approximation to sqrt(3)/2 than is e/pi. Continued fraction approximations are great! --DrMath 07:23, 7 September 2013 (UTC)

How could he forget 1 gallon ≈ 0.1337 ft³?! 67.188.195.182 00:51, 8 September 2013 (UTC)

- There's also "(-1)*(Zeta(-1))-1 is approximately 12". ColorfulGalaxy (talk) 20:35, 11 December 2022 (UTC)

Worth mentioning that Wolfram Alpha now officially recognizes the White House switchboard constant and the Jenny constant. 86.164.243.91 18:28, 8 October 2013 (UTC)

Maybe we should add the [Extension:LaTeXSVG LaTeX extension] to make it easier to transcribe these equations. -- 108.162.219.220 23:02, 16 December 2013 (UTC)

- Protip - Does anyone see the correct equation?

Maybe this is just an other Wolfram Alpha error, like we recently have had here: 1292: Pi vs. Tau. All equations still look invalid to me.

- √2 = 3/5 + π/(7-π): is impossible because √2 is an irrational number and no equation can match.

- cos(π/7) + cos(3π/7) + cos(5π/7) = 1/2: could only match if cos(x) + cos(3x) + cos(5x) = 1/2 would be valid, because π/7 is also an irrational number.

- γ = e/34 + e/5 or γ = e/54 + e/5: would mean that a sum of two irrational numbers do fit to the Gamma Constant. Impossible.

- √5 = 13 + 4π / 24 - 4π: √5 and π are irrational numbers, there is no way to match them in any equation like this.

- Σ 1/nn = ln(3)e: doesn't make any sense either.

Maybe Miss Lenhart can help. --Dgbrt (talk) 21:41, 17 December 2013 (UTC)

cos(π/7) + cos(3π/7) + cos(5π/7) = 1/2 is exactly correct.

Let a=π/7, b=3π/7, and c=5π/7, then (cosa+cosb+cosc)⋅2sina=2cosasina+2cosbsina+2coscsina=sin2a+sin(b+a)−sin(b−a)+sin(c+a)−sin(c−a)=sin(2π/7)+sin(4π/7)−sin(2π/7)+sin(6π/7)−sin(4π/7)=sin(6π/7)=sin(π/7)=sina

Hence, cos(π/7) + cos(3π/7) + cos(5π/7) = sin(π/7) / 2sin(π/7) = 1/2 108.162.216.74 01:57, 16 January 2014 (UTC)

- What is this: sin(6π/7)=sin(π/7) ? A new math is born... --Dgbrt (talk) 20:49, 16 January 2014 (UTC)

- Actually it does. My proof is geometric: the sines of two supplementary angles (angle a + angle b = π (in radians)) are equivalent because they necessarily have the same x height in a Cartesian plane. Look on a unit circle, or even a sine function. Also, Calculus and most other mathematics use radians over degrees because they make the functions simpler and eliminate irrationality when a trig function shows up, but physics uses degrees because it's easier to understand and taught first. Anonymous 01:27, 13 February 2014 (UTC)

- As an aside, just how far along in math are you? Radian measure is taught in high school (at least the good ones). Anonymous 13:24, 13 February 2014 (UTC)

- Sure, I was wrong at my last statement. sin(6π/7)=sin(π/7) is correct by using the radian measure. But just change π/7 to π/77 would give a very different result on that formular here. I still can't figure out why PI divided by the number 7 should be that unique, PI divided by 77 should be the same. My fault is: I still can't find the Nerd Sniping here. And we all do know that Randall did use wrong WolframAlpha results here. According to the last question: I'm very well on Math, that's because I want to understand this. This is like 0.999=1. --Dgbrt (talk) 22:01, 13 February 2014 (UTC)

- Ah, I see. I think it has to do with the way e^i*π breaks down, as one of the answers shown in the corresponding link explains, but other answers rely on various angle identities (including the supplementary sines one in the proof above). Anonymous 03:10, 14 February 2014 (UTC) (PS, have you checked 545 lately? I answered your question there, too)

- As per the derivation from january 16 , you can use any a,b,c that satisfies this set of equations: 2 a = b - a, a + b = c- a, c + a = π - a. This is due to the fact that sin(x) = sin(π-x), and what was derived the 16th. 173.245.53.199 12:38, 21 February 2014 (UTC)

- Dgbrt: If not convinced by the proofs linked to in the "explanation" part, you might want to try this: [1]. I'm sure you'll find inspiration for similar formulas using PI over [any odd integer]. Your assumption that Randall used WolframAlpha for this very identity is probably wrong. This is a very well-known formula that appears in many high school books, and I am pretty sure it is part of Randall's culture. And this has nothing to do with 1=1. As for your original post,

- √2 = (√2-1)/((4-2)π/2-π)+1 : Is this what you call "matching an equation" to √2?

- So what you mean is that if an equation is true for an irrational number, then it must be for any real number? Like, (√2)^2 = 2, but because √2 is irrational, then x^2=2 (for all x?)

- This one's a bit tough. You will probably agree that γ-√2 is irrational. And so is √2. What about their sum?

- Well, maybe it doesn't to you. But is Σ n-2 = π^2/6 any better? Well, this one is true (using Fourier's expansion of the rectangular function).

- Finally,

- √2 = 3/5 + π/(7-π) is false because it would imply that π is an algebraic number

- cos(π/7) + cos(3π/7) + cos(5π/7) = 1/2 is true, and proven by many

- γ = e/34 + e/5 seems false. But there doesn't seem to be a quick way to disprove.

- Σ 1/nn = ln(3)e seems false, but I can't see why. 108.162.210.234 09:15, 11 May 2014 (UTC)

- Ah, I see. I think it has to do with the way e^i*π breaks down, as one of the answers shown in the corresponding link explains, but other answers rely on various angle identities (including the supplementary sines one in the proof above). Anonymous 03:10, 14 February 2014 (UTC) (PS, have you checked 545 lately? I answered your question there, too)

- Sure, I was wrong at my last statement. sin(6π/7)=sin(π/7) is correct by using the radian measure. But just change π/7 to π/77 would give a very different result on that formular here. I still can't figure out why PI divided by the number 7 should be that unique, PI divided by 77 should be the same. My fault is: I still can't find the Nerd Sniping here. And we all do know that Randall did use wrong WolframAlpha results here. According to the last question: I'm very well on Math, that's because I want to understand this. This is like 0.999=1. --Dgbrt (talk) 22:01, 13 February 2014 (UTC)

- Dgbrt, yes, sin(6π/7)=sin(π/7). Simple proof: sin(6π/7)=sin(π-π/7)=sin(π)cos(-π/7)+cos(π)sin(-π/7)=0*cos(-π/7)+(-1)*(-sin(π/7))=0+sin(π/7)=sin(π/7) 108.162.215.89 02:34, 20 May 2014 (UTC)

- So, still incomplete?

Where's our (in)complete judge? 199.27.128.186 19:21, 18 December 2013 (UTC)

- The protip is still a mystery. I'm calling for help a few lines above. --Dgbrt (talk) 21:16, 18 December 2013 (UTC)

- The cosine one, in radians, is correct 141.101.88.225 12:54, 28 April 2014 (UTC)

The 'Seconds in a year' ones remind me of one of my favorite quotes: "How many seconds are there in a year? If I tell you there are 3.155 x 10^7, you won't even try to remember it. On the other hand, who could forget that, to within half a percent, pi seconds is a nanocentury" -- Tom Duff, Bell Labs. Beolach (talk) 19:14, 17 April 2014 (UTC)

- cos(pi/7) + cos(3pi/7) + cos(5pi/7) = 1/2 ???

Why the hell the divider seven makes the difference?

- cos(pi) + cos(3*pi) + cos(5*pi) = -3

- cos(pi/8) + cos(3*pi/8) + cos(5*pi/8) = 0.92387953251128675612818318939678828682241662586364...

So why the "magic" prime number seven produces this exact result? I know radians and π/7 is just a small part of a circle which is 2π. One prove claims that sin(6π/7) equals to sin(π/7); my best calculator can't show a difference. Of course sin(6π) equals to sin(π), in radians, BUT sin(6π/8) is NOT equal to sin(π/8). So if the number 7 plays a magic rule here this would be "one of the", no... the BIGGEST mystery in mathematics forever. --Dgbrt (talk) 23:03, 16 May 2014 (UTC)

- Dgbrt, please see my answer from 11 May 2014 up there. Any odd integer will do, as long as you sum enough of cos(pi/[thing]).

- Let's try with 5 : cos(pi/5) + cos (3pi/5) = 1/2.

- cos(pi/5) is actually (1+sqrt(5))/4. Additionally, sin(pi/10) is very close to (1 foot/1 meter).

- With 9 : cos(pi/9)+ cos(3pi/9) + cos (5pi/9) + cos(7pi/9) = 1/2 OR cos(pi/9) + cos (5pi/9) + cos(7pi/9) = 0

- No big mystery around here. Just a beautiful formula :) I think there are similar formulas with cosines and even integers. I'll post them here if I have time. Varal7 (talk) 09:56, 17 May 2014 (UTC)

- You mixing up to different equations and even not prove them. If there is any prove to a mathematician I would accept and include a proper explain for non math people here. We still have to find a prove. And I do not trust my calculators, we just have to explain why even cos(pi/5) + cos (3pi/5) is also nearly the same. This issue is still not explained. So please give us a explain. And a PROTIP: This does not work with Integers, PI is infinite--Dgbrt (talk) 17:55, 17 May 2014 (UTC)

- Okay. If I understood what you said.

- I mix up different topics. -> True. From now on, we'll just focus on the cosine one.

- You ask for a proof/explanation. -> My opinion is those are two different requests. Maybe that's why you use the distinction between math people/not math people. For a proof, please read further. What I exposed above are just other "fun experiments" we could do. e.g : [2].

- You do not trust your calculators -> Great. I don't either. (Well more accurately, I trust mine to 10^-8, so I would definitely not use it to prove any of the discussed equations in PROTIP). That's why we'll prove the formulas we assert.

- "This does not work with integers" -> Well, I got myself misunderstood. It would probably have been better if I had said: the following formula is true for all integer n. sum_{k=0}^{n-1}{cos((2k+1)*pi/(2n+1)). But It's harder to read, so just say. Choose any odd integer, say N=2n+1. Then start the following sum. cos(pi/N) + cos(3pi/N) + … and stop when the numerator is cos((N-2)pi/N). Then the result is 1/2. And that's what we'll prove, a few lines down from here.

- "Pi is infinite" -> That's a common misconception. What you mean is, Pi is irrational. (Fun fact: Pi is a transcendental number. Quite difficult theorem. Lindeman proved it in 1882. Hence, if we identify the real number x with the Q-vector space Q[x], it would make sense to say that "x is infinite" because, the Q-vector space Q[x] is indeed of infinite dimension. But then, that's not what mathematicians do). I think Vi Hart made a video where she addresses this issue (or was it someone else?). Anyway, I might come to that point some other time in the future.

- Okay, so now let's first prove the protip formula. Well first, here is the link that the explainxkcd wiki points to: [3]. Most of them are correct. Some are more ugly than others. I'll adapt the last one.

- We need a complex numbers. (I choosed this because I think explainxkcd readers are fine with this. See comic 179). I will be using dots to show the steps of my proof. Please allow me an extra level of indent for clarity's sake.

- Proof

- *Let z be a primitive 14-th root of unity (the reader doesn't need to understand the 3 last words). Just say z = exp(i*pi/7) = cos(pi/7) + i sin(pi/7). Using Euler's formula.

- *We have z^14-1 = (exp(i*pi/7))^14-1 = exp(i*2pi) - 1 = 0. Using exponential law for integer powers, as seen in this article: De Moivre's formula.

- *Now let's factor: z^14-1 = (z^7-1)(z^7+1) = (z^7-1)(z+1)(z^6-z^5+z^4-z^3+z^2-z+1) = (z^7-1)(z+1)*Phi_14(z). where Phi_14(X)= X^6-X^5+X^4-X^3+X^2-X+1, (see cycltomic polynomial). Now, because z^7-1 = (exp(i*pi/7))^7-1 = exp(i*pi)-1 = -2. And because z is not -1, the two first factors are not 0 so, Phi_14(z) = 0, which is already a pretty awesome equality.

- *Note that exp(i*pi/7)*exp(i*6pi/7)= exp(i*pi)=-1. So the inverse of z is -exp(i*6pi/7). But we also know that it is exp(-i*pi/7). Well. That was just a fancy way to prove that exp(-i*pi/7) = - exp(i*6pi/7). Good enough. The same holds for exp(-i*3pi/7) = exp(i*14pi/7)*exp(-i*3pi/7)=exp(i*11pi/7)=exp(i*7pi/7)*exp(i*4pi/7)=-exp(i*4pi/7). And the exact same calculation shows that exp(-i*5pi/7)=-exp(i*2pi/7). Alright.

- *Now, use that for any x, we have cos(x) = (exp(ix)+exp(-ix))/2. See here. Let's calculate twice the sum of the left hand side. 2(cos(pi/7)+cos(3pi/7)+cos(5pi/7))= exp(i*pi/7) + expi(-i*pi/7) + exp(3pi/7) + exp(-3pi/7) + exp(5pi/7) +exp(-5pi/7) = exp(i*pi/7)-exp(i*2pi/7)+exp(i*3pi/7)-exp(i*4pi/7)+exp(i*5pi/7)-exp(i*6pi/7) = -Phi_14(z) +1 = 1.

- * So dividing both sides by 2, we get what we want. Pfew.

- Why is 7 so special? Well it isn't. Let's prove it for 9.

- Let z = exp(i*pi/9) = cos(pi/9) + i sin(pi/9). We have z^18-1 = 0, and z^9-1 and z+1 are not 0, so using the same factorisation, Phi_18(z) = z^8-z^7+z^6-z^5+z^4-z^3+z^2-z+1 = 0.

- Hence, the conclusion follow from: 2(cos(pi/9) + cos(3pi/9) + cos(5pi/9) + cos(7pi/9)) = exp(i*pi/9) + exp(-i*pi/9) + exp(i*3pi/9) + exp(-i*3pi/9) + exp(i*5pi/9) + exp(-i*5pi/9) + exp(i*7pi/9) + exp(-i*7pi/9) = -Phi_18(z)+1 = 1.

- Well, well. I hope you kinda see the pattern. Dgbrt, I know you hate typos, and I'm pretty sure that in this long text lay many of them. So I apologize, and I will correct them later. The following paragraph was posted after I started my text but before I finished mine. It wasn't signed so I will just leave it down there. It's another valid straightforward proof. Oh. And Friendly TIP: Don't say protip when you're not pro. Varal7 (talk) 21:50, 17 May 2014 (UTC)

- Okay. If I understood what you said.

The valid identity cos(pi/7)+cos(3pi/7)+cos(5pi/7)=1/2 was correctly proved by the writer at 108.162.216.74 above. For a different proof, consider the complex number z = cos(pi/7)+i sin(pi/7) corresponding to rotation of the complex plane by pi/7 radians, i.e., 1/14th of a full rotation. It satisfies z^{14} -1 = 0 (z to the fourteenth is one). Dividing by z-1 gives z^{13} + z^{12} + ... + z + 1 = 0. The same argument, starting with z^2 corresponding to 1/7th of a full rotation, gives z^{12} + z^{10} + ... z^2 + 1 = 0. Taking the difference, we get z^{13} + z^{11} + ... + z^3 + z = 0. Looking only at the real parts, we get cos(13pi/7) + cos(11pi/7) + cos(9pi/7) + cos(7pi/7) + cos(5pi/7) + cos(3pi/7) + cos(pi/7) = 0. Here cos(13pi/7) = cos(pi/7), cos(11pi/7) = cos(3pi/7) and cos(9pi/7) = cos(5pi/7), since cos is even and 2pi-periodic. Finally cos(7pi/7) = -1, so 2(cos(pi/7) + cos(3pi/7) + cos(5pi/7)) - 1 = 0, which you can rewrite as the desired identity. All of this can be clearly visualized using a regular 14-gon, so a proof with pictures is possible. 141.101.81.216 (talk) (please sign your comments with ~~~~)

- 99 is sexual reference?

In first explanation it says: "99^8 and 69^8 are sexual references". 69 I understand, but what would 99 refer too? --173.245.53.167 17:38, 18 May 2014 (UTC)

- see 487: Numerical Sex Positions141.101.70.181 15:33, 20 July 2014 (UTC)

I'd add pi = (9^2 + (19^2)/22)^(1/4) 198.41.230.73 02:41, 13 May 2015 (UTC)

Yet another proof of cos(π/7) + cos(3π/7) + cos(5π/7) = 1/2 — Use the multi-angle formula cos(7θ) = 64(cos θ)^7 − 112(cos θ)^5 + 56(cos θ)^3 − 7(cos θ),

and assume cos(7θ)=−1; then 7θ=π, 3π, 5π, 7π, etc.

Let x=cos θ, then x = cos(π/7), cos(3π/7), cos(5π/7), cos(7π/7), etc.

Now one could actually solve 64x^7 − 112x^5 + 56x^3 − 7x + 1 = (x+1)(8x^3 − 4x^2 − 4x + 1)^2 = 0,

but it’s easier to argue that cos(π/7), cos(3π/7), cos(5π/7) are the 3 roots of the cubic equation 8x^3 − 4x^2 − 4x + 1,

and so (using the relationship of the roots and the coefficients) their sum is −(−4)/8 = 1/2.

Yosei (talk) 08:19, 17 February 2019 (UTC)

One step closer to the elusive log(x)^e In searching for an error correction term of the Taylor expansion of -x log(x) at degree n around 1, I found the term (1 - x)^(n * e)/n. It felt so close to having an actual log(x)^e appearing in a useful equation... Hope I would be able to see one someday. Mumingpo (talk) 13:36, 6 May 2021 (UTC)

This page is one of the very few pages on Explain XKCD that are cited on OEIS. --ColorfulGalaxy (talk) 11:40, 16 January 2023 (UTC)

![\begin{align}

&= \frac {2 \cos \frac{\pi}{7} \sin \frac{\pi}{7} + \left[\sin \left(\frac{3\pi}{7} + \frac{\pi}{7}\right) - \sin \left(\frac{3\pi}{7} - \frac{\pi}{7}\right) \right] + \left[\sin \left(\frac{5\pi}{7} + \frac{\pi}{7}\right) - \sin \left(\frac{5\pi}{7} - \frac{\pi}{7}\right) \right]} {2 \sin\frac{\pi}{7}} \\

&= \frac {2 \cos \frac{\pi}{7} \sin \frac{\pi}{7} + \left[\sin \frac{4\pi}{7} - \sin \frac{2\pi}{7} \right] + \left[\sin \frac{6\pi}{7} - \sin \frac{4\pi}{7} \right]} {2 \sin\frac{\pi}{7}}

\end{align}](/wiki/images/math/7/5/3/7538f439196ac0fef0fcff1b09b738db.png)

![\begin{align}

&= \frac {\sin \frac{2\pi}{7} + \left[\sin \frac{4\pi}{7} - \sin \frac{2\pi}{7} \right] + \left[\sin \frac{6\pi}{7} - \sin \frac{4\pi}{7} \right]} {2 \sin\frac{\pi}{7}} \\

&= \frac {\sin \frac{6\pi}{7} + \left[\sin \frac{4\pi}{7} - \sin \frac{4\pi}{7} \right] + \left[\sin \frac{2\pi}{7} - \sin \frac{2\pi}{7} \right]} {2 \sin\frac{\pi}{7}} \\

&= \frac {\sin \frac{6\pi}{7} } {2 \sin\frac{\pi}{7}}

\end{align}](/wiki/images/math/5/0/3/503c8bf162c3c5cb047e8814c311452e.png)