3092: Baker's Units

| Baker's Units |

Title text: 169 is a baker's gross. |

Explanation

| This is one of 58 incomplete explanations: This page was created by a baker's bot. Don't remove this notice too soon. If you can fix this issue, edit the page! |

A baker's dozen is 13 units of bakery goods, as opposed to the normal dozen meaning 12. That tradition began when salesmen in medieval times had to pay penalties (in some regions, draconian ones) when customers were sold one item short, or not enough weight. To avoid the customer complaints and the penalty, bakers added a safety margin that allowed them to still serve a dozen in a hurry: If a miscount happens the baker would have given out twelve rolls just as ordered; if no miscount happens the baker is just short of one inexpensive item).

Randall proceeds to apply this principle to other things. A reader might anticipate this means simply applying a count of 13 of a thing, or adding one to the most prominent quantity. But it slowly becomes clear that, instead, Randall finds something about the thing that is comprised of 12 units, changes that to 13, and demonstrates the logical consequence.

The results gradually become more unexpected and silly:

- Imperial feet are 12 inches long; a baker's foot would be 13 inches long.

- Noon is 12:00 o'clock ("twelve hundred hours/Juliett" in 24-hour military parlance); baker's noon would be 1 o'clock PM ("thirteen hundred hours", etc).

- Dodecahedra have 12 faces ("dodeca" = "twelve"). The best-known kind of dodecahedron is the regular dodecahedron, a Platonic solid whose faces are regular pentagons (the shape that most d12s take the form of), but there are others such as the rhombic dodecahedron and pyritohedron. Baker's ones are tridecahedra with triangles, squares and pentagons (which are not Platonic solids and cannot be used as dice due to having multiple face types, rendering dice-based games unbalanced).

- Years have 12 months; a baker would celebrate New Year's Eve after an extra thirteenth month, on January 31 (and implying that their New Year would shift forward each year).

- Octaves are comprised of 12 half-steps (a half-step is the distance between adjacent notes, such as F and F#). A baker’s octave would have 13 half-steps (corresponding to a minor ninth) and cause problems in musical composition, as octaves (of the baker’s variety) would be dissonant, instead of being consonant. However, Randall's musical notation actually shows a major ninth, with fourteen half-steps. If he wanted thirteen half-steps, Randall could have used D♭ instead of D, or drawn a bass clef instead of a treble clef.

- Trial juries in the Anglo-Saxon law tradition (Common Law) consist of 12 peers. The baker’s jury has 13 peers. This might be considered to make little practical difference, though it does mean that (in situations where a jury is allowed to present a majority verdict instead of requiring unanimity), the odd number of jurors would prevent exact ties. (Note that Scottish juries, in particular, start with the expectation of there being 15 jurors, and may well end up reduced to 13 or even 12.)

- The Flag of Europe has 12 stars forming a circle (as a symbol of harmony); unlike in the US flag, the stars do not represent member states. The flag was first adopted by the Council of Europe in 1955, when it already had 13 members - today there are over 40. The European Communities adopted the Flag of Europe in 1986 before the EC turned into the European Union. A 13th star could potentially be added to the baker's EU flag nevertheless without major damage to the symbol. In the United States, thirteen stars in a circle is associated with the Betsy Ross flag, the first U.S. flag.

- Magnesium is the element with the ordinal number 12, with twelve protons. Aluminum is number 13, and is a very different material.[citation needed] "Baker's magnesium" actually has more applications in baking (namely, tinfoil, which is actually made of aluminum, not tin), but it does not have as much nutritional value.

- In the title text, a count of 144 (12x12) is a gross. Thus, 169 (13x13) would be a baker's gross, an addition of not just one but 25 units.

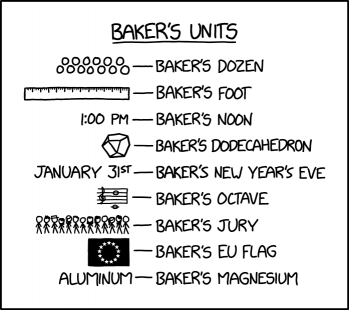

Transcript

| This is one of 38 incomplete transcripts: Don't remove this notice too soon. If you can fix this issue, edit the page! |

- Baker's units

- [A formation comprising 13 items] - Baker's dozen

- [A ruler divided into 13 parts] - Baker's foot

- 1:00 PM - Baker's noon

- [A shape with 13 faces] - Baker's dedecahedron

- January 31st - Baker's New Year's Eve

- [Two notes on a staff 13 half-steps apart] - Baker's octave

- [13 people standing in a row] - Baker's jury

- [A flag with 13 stars forming a circle] - Baker's EU flag

- Aluminum - Baker's magnesium

Discussion

Why did he go with only 9/13ths of a Baker's List? 172.69.65.8 23:48, 21 May 2025 (UTC)

- This suggests that the "expected" length of a list is 12. ISaveXKCDpapers (talk) 07:24, 22 May 2025 (UTC)

A ruler for a "baker's foot" is, apparently, similar to a metal casting patternmaker's shrink rule, although in practice those top out at 2.5%, versus 13/12ths or 8.{3}%. JohnHawkinson (talk) 23:59, 21 May 2025 (UTC)

It appears to me like g marked by the g-clef is on the second space making the notes b and c which wound be 13 semitones apart. Two compensating errors or just a bit more cleverness for lagniappe?Lordpishky (talk) 01:07, 22 May 2025 (UTC)

There's also baker's percentages. All the ingredients are defined as a percentage of the weight of the flour. So if you have 1kg (1000gr) of flour and 600ml (gr) of water then the water is said to be 60% hydration.

"which are not Platonic solids and cannot be used as dice due to having multiple face types, rendering dice-based games unbalanced"

Being a platonic solid is sufficient, but not necessary, for a fair die. The simplest shape for a fair 13-sided die that I can think of off the top of my head is two 6-sided pyramids joined at the base, with one of them truncated for the 13th side. To make it fair, the lengths of the pyramids and the truncation would have to be fine-tuned, but that's certainly possible. Where's John von Neumann when you need him? --Coconut Galaxy (talk) 10:45, 22 May 2025 (UTC)

- I'd imagined two 6SPs joined by a barrel (maybe a smooth ring, maybe a set of squares/triangles for either a primsatic or anti-prismatic hexagonal-faced centre-section, but all the way round counting for the same 'roll', either way.) Too short, the chances of landing on the 'edge' is greatly lowered, too long a mid-section, it'll be almost impossible to land anywhere but on it (imagine a pencil, sharpened at both ends).

- Thus there's a point where a symmetrical (lengthwise, as well as by rotations) shape has just enough 'middle band' to have equal chances of landing with that as with any other single 'point ends' face (landed on; with it being prismatic, an obvious and readable 'face-up' also presenting itself).

- But it'd be a tight specification, perhaps need emperical testing. The angle between adjacent 'pointy end' triangles with each other would be different from the angle between any of them and the 'barrel', so sharper or rounder edges between faces (not an issue with platonics, as the rolling-resistance is equal by all edge-/corner-intersections being exactly as equal as the faces are) could decrease or increase the probability of mid-roll tumbling. As could deliberately rolling along the prismatic axis to either try to stay on 'that face' or to make it more likely thst the random-walk of tumbles sends it off it (I'd have to run a few simulations; either bias, or both, might be easiest to manipulate by a bit of practiced handling).

- I do rather envisage it being 'numbered' as having +1..+6 and -1 to -6 on the pyramidal ends (by tradition, every +n is on the opposite triangle of the opposite pyramid to its -n counterpart, but you can alternate +s and -s between adjacent pyramid faces), and 0 on the mid-section, so that it'll give symmetrical chance distribution across the good/bad range, which might make the "natural zero" midpoint a not quite so vital number to ensure is as strictly equally likely as all the others. Alternatively, 1..12 (similarly distributed to add up to 13 when taking sat-upon and face-up together) leaves either 13 (beyond-lucky) or 0 (the most critical of fails) on the ring which is deliberately mad less-likely to get.

- For even better game-symmetry, supply two "D12±" dice, design your system on rolling them in pairs. Rolling either the 0 on the 0..12 or 13 on the 1..13 gives you the critical [failure|success] on top of the sum-of-the-dice result. Rolling both 0 and 13 invokes a "critical funny" result (or a "fortunate fail"/"pyrrhic success"), in whatever way suits the game style, current encounter or even the scenario/plot's ultimate challenge. (To contrast a Toons-type game from a Paranoia one, or a straight-up Dungeon-Dive where extreme peril/hilarity needs to be more tightly modulated by the GM.)

- Of course, I'm generally working on the assumption that "12 (or 13) is good, 1 (or 0) is bad", but there's nothing to say the D13 rolls are for the players, and a D13 with a higher-than-normal chance of a 13 would be just the thing for a Horror-themed RPG, invoking the latest plot-stage of whatever cthuluesque escalation is lurking and awaiting the (un?)wary players. I've played all kinds of dice-led games (favourite variation, amongst them is "Babylon 5 dice" - roll two D6, one red, one green... lowest pips counts, dice-colour dictates if it's positive or negative (upon the baseline for the task attempted), equal dice is zero-offset except for double-6/double-1 which are critical success/failure ...all nicely symmetrical, as a modified version of a 2D6 distribution 'around' the result of 7), and a 'cursed dice' would not even be amongst the strangest treatments I've seen. 172.69.224.82 13:35, 22 May 2025 (UTC)

Is “baker’s noon” a distant jab at Daylight Saving Time? HaruruChanDesu (talk) 08:52, 23 May 2025 (UTC)

The clef in the Baker's Octave seems to mark the *gap* between 2nd and 3rd line from the bottom. A normal treble clef has a "ring" part spanning two line gaps, with the "dot" pinning the G to the middle line. This one is closer to a one-gap ring with the dot in the gap. That might be a layman's excusable sloppiness ... or it could well be intentional. In the latter case, the notes shown would indeed be B3 and C5, making the interval a 13-semitone minor 9th. Sesc (talk) 09:46, 23 May 2025 (UTC)

Couldn't you also get a Baker's Octave by spacing your notes at root13(2) instead of the traditional semitone at root12(2) apart?

My main objection to the possibility of giving out not-quite-a-dozen loaves (whether 'rectangular tin' type or round 'farmhouse loaves', whatever the style of loaf a contemporary baker would have produced in that era) is that it is very easy to visually confirm a dozen regularly-sized items, because a dozen is so much easier to visualise: A 3x4 array (square or skewed) is very easy to compare to one with one item missing (even if you have difficulty with 2x5 stretching out too far to stay unragged and even, when you can't even count as far as the fingers on one hand). Even piled up, 2x2x3 (whichever way the '3' lies) works well. (Put in a square pyramid, for the really fancy, three layers gives 14, so removing the pinacle for a 3x3 with only 2x2 on top could give 13, but why not take off/leave one more? Triangularly pyramid-stacked, say for round-loaves, three stable layers is 10, so add a couple more. Four stacks of 2-and-1 or two stacks of 3-2-and-1 'vertical wedge's would give you 12 without exceeding any easy counting. Of course, the disnumerate would have to learn "the patterns", all of which would be less obvious than a flat or stacked purely square-based array.) But who are these bakers who are baking in bulk (presumably with a degree of consistency between their loaves/other-baked-products) and frequently selling in bulk (as opposed to a farthing or ha'penny loaf, or two, per average household per day, so probably a sufficiently large landed household with staff/servants, yet not large enough to have a dedicated in-house baker/cooking-staff doing their own on-demand baking) that they're regularly and rapidly passing over handfulls of larye, loose baked-product over the counter and yet aren't taking just enough extra effort to ensure that they're not diddling the customer (or, more of immediate concern, diddling themselves through sheer carelessness!). And not in a manner that even only the partially-numerate (both sides of of the purchase?) can easily and correctly judge by eye (to consistently bake decent loaves, you're probably going to get very good at judging relative volumes/weights of even powders!). - And, here's a practical excercise: get a bucket of tennis balls (or anything large enough for one to occupy a hand) and manually transfer them from that bucket to another. I bet most people will dive in with both hands and grab two at a time in synchrony (or stocato left-right/left-right/..., or vice-versa). Very hard to do that almost six times and end up with an off by one error. Do it enough times, perhaps you even tend to grab two balls, use them to support a third between them to transfer three in each transfer... Hup, hup, hup, hup! That's your dozen, and bread can be handled in the same manner (careful not to damage the crust...). Small enough balls(/pastries), or big enough hands, to fit two in each hand? "Hup, hup, hup" will do your dozen, and you'll already know if your grabs failed to hold two of them (whether by overgrab, side-grab, scooping up, etc). ...I'm far more convinced that the (or, at least, a) true source of the Baker's Dozen was just as a "Loss Leader". For those who could buy such items (one of the few daily essentials that could be "mass produced", in a way) a dozen at a time, they were given an extra item for being a good customer. A little extra goodwill, with a loss of potential profit on that single transaction (8⅓% of gross) less than a typical tythe (⅒th, 10%). (Not that tythes worked that way, exactly.) 172.70.163.166 12:07, 23 May 2025 (UTC)

- It is actually easy to count to 12 on one hand, just use the thumb to count the bones in the other fingers. It even leaves the other hand free to transfer whatever you're counting. (Western culture simply sucks at counting on fingers.) --172.71.164.102 06:20, 24 May 2025 (UTC)

- My understanding of it was that it was to avoid shorting the customer by weight, not by count. There can be non-negligible variance in the weight of baked loaves/rolls even if the dough weight was identical, and there's also plenty of potential for error in the dough weight. But it's extremely unlikely that the weights will be off by enough that a 13th item won't make up the possible shortfall. Looking it up, this seems to be the leading theory, but there's no definite confirmation from historical sources. 162.158.42.117 23:00, 23 May 2025 (UTC)

- My nana told me the 13th loaf in a bakers dozen was to make up for any shortfall in the weight of the loaves. I never heard that a baker would be penalized if he charged for 12 but gave you 11. If the buyer does not count the loaves, nana would say that is the buyer's fault. Nana was from the old country. 162.158.167.191 (talk) 04:31, 24 May 2025 (please sign your comments with ~~~~)

Title text: 169 is a baker's gross. I thought a Baker's gross described a disqusting pastry. These Are Not The Comments You Are Looking For (talk) 02:05, 25 May 2025 (UTC)

Every day my workload supposed to finish by noon is still not finished at Baker’s noon, so I empathize with the concept. 物灵 (talk) 05:13, 25 May 2025 (UTC)

The Baker’s octave is tied with the major sixth for the prettiest interval, in my opinion. In fact, do both at once (so C A D for instance) for an unusual but pretty chord.172.70.174.78 12:38, 25 May 2025 (UTC)

- Except that a baker's octave should probably be C to D-flat, and there's probably either an error or a trick in the cartoon. 64.114.211.60 05:51, 29 September 2025 (UTC)

You get an extra letter's worth of baker's magnesium if you're British. :-D 172.69.79.190 00:26, 26 May 2025 (UTC)

Some other "numbers in baker's units":

- Baker's trillion (1013) – 13 zeros instead of 12, so ten trillion

- Baker's undecillion (duodecillion, 103(13) = 1039) – 13 groups of 3 instead of 12

- Baker's duodecillion (tredecillion, 103(14) = 1042) – 14 is the 13th integer larger than 1, and so "duodecim" is replaced with "tredecim".