3181: Jumping Frog Radius

| Jumping Frog Radius |

Title text: Earth's r_jf is approximately 1.5 light-days, leading to general relativity's successful prediction that all the frogs in the Solar System should be found collected on the surface of the Earth. |

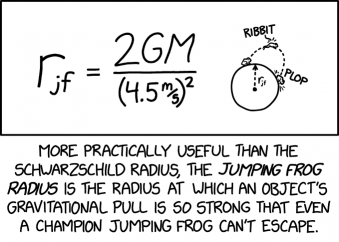

Explanation[edit]

The Schwarzschild radius is essentially the size of a black hole -- the maximum distance from the center where gravity is so strong that light can't escape. It is part of a solution to Einstein's field equations. It is usually calculated as

- rs = (2*G*M) / c2

where G is the gravitational constant, M is the mass of the object, and c is the speed of light. If M were the mass of the Earth, it would give the Schwarzschild radius for the Earth, which is about 9 mm. (If all of Earth's mass were compressed into a sphere of a bit less than 2 cm in diameter, it would become a black hole.)

The comic suggests a more useful radius: the Jumping Frog radius rjf, which is the size of a "planet" such that its gravity keeps a champion jumping frog from being able to achieve escape velocity. Thus Randall has instead of c, the 299,792,458 m/s speed of light, used a much smaller value of 4.5 m/s, to represent the maximum speed of a jumping frog. It is possible that Randall got that value from this paper, which on page 179 puts an upper limit on the maximum velocity of adult Australian striped rocket frogs at 4.52 m/s. (The frog is shown making a "ribbit" sound, which is made by Pacific tree frogs and their relatives in North America and not by rocket frogs, but it's widely attributed to frogs all over the world.)

The drawing to the right of the formula shows a planet with exactly the radius rjf. Thus the frog can jump really high compared to the planet's size (in this case about as high as the planet's radius), before it falls back down. This implies that the frog is jumping at somewhat less than the 4.5 m/s needed to escape.

The title text points out that the rjf of the Earth is about 1.5 light days, which is about 7 times the distance to Pluto (compare to the 9 mm Schwarzschild radius). Since Earth's radius is much smaller than this, no frogs will be able to escape, so all frogs that stray into Earth's gravitational well would collect here on Earth. As far as we know, all the frogs in the Solar System are on Earth[citation needed], so the data apparently matches the theory. However, the reasoning is incorrect, as many other astronomical bodies in our solar system also have rjf greater than their physical radius. If a frog were to be on any of those other bodies, it wouldn't be able to jump away to fall to Earth. A flawed argument neither supports nor refutes the conclusion, although it is true as far as we know that all frogs in the solar system do live on Earth.

If you were to take a frog off the earth and put it in a tiny frog space suit, which somehow did not unduly inhibit its movement, it could jump off any number of the smaller bodies in the solar system. However, few of these bodies are small/low-mass enough for a frog to escape them, and large enough and close enough for us to observe them and accurately estimate their escape velocities. (The diameter of asteroid 4942 Munroe is known to be about 3.45 km, but its shape and mass are unknown. Its surface has an exceptionally high albedo of 0.936, which suggests that the surface is mostly some kind of ice. If we assume that asteroid Munroe is spherical and entirely composed of water ice, with a density close to 1 g/cm3, its mass is 2.16 × 1010 kg, and its escape velocity is 0.041 m/s. If instead it's a solid sphere of meteoric iron/nickel with a density of about 8 g/cm3, its mass is 1.72 × 1011 kg, and its escape velocity is 0.115 m/s. In either case, Space Frog would have no trouble jumping away from Munroe.) Some examples:

| Celestial Body | Escape Velocity (m/s) | Frog Escape? | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Deimos | 5.6 | X | The smaller of Mars's two moons |

| Ersa | ca. 1 | ✓ | Minor moon of Jupiter |

| Halley's Comet | ca. 2 | ✓ | Notable comet, orbiting the sun every 76 years |

Transcript[edit]

- [The panel shows a large formula to the left and a small drawing to the right. The formula's right side is drawn above and below the division line:]

- rjf = 2GM / (4.5 m/s)2

- [The drawing to the right shows a very small planet with the radius indicated with a labeled dotted arrow pointing from the center straight up to the edge of the planet. A frog is shown jumping on the surface. This is indicated with a parabolic dotted line going from a frog sitting on the surface near the top of the planet, up to the frog shown soaring through the air with its limbs stretched out about as high above the surface as the planet's radius. At this point the frog is making a sound. Then the dotted line goes down to about a quarter of the way around the planet where the frog lands making a noise, with lines around the frog representing the impact.]

- Arrow label: rjf

- Frog: Ribbit

- Landing: Plop

- [Caption below the panel:]

- More practically useful than the Schwarzschild radius, the Jumping Frog Radius is the radius at which an object's gravitational pull is so strong that even a champion jumping frog can't escape.

Discussion

first Qwertyuiopfromdefly (talk) 05:17, 16 December 2025 (UTC)

Question: Would a correct interpretation be "if a champion jumping frog were to be located just under 1.5 light-days from earth, and if there we're no other gravitational bodies nearby, and if said frog then performed its mightiest jump directly away from earth, then the frog would eventually be overcome by Earth's gravitational field and would eventually land on Earth's surface"? Pgn674 (talk) 06:26, 16 December 2025 (UTC)

- I guess that is exactly how it should be interpreted. Or more interesting if it was just outside this radius and somehow could gain exactly 4,5 m/s extra speed then it would escape Earth (if there was anything to push of against that was heavy enough to move basically only the frog forward, then that would change the mass behind the frog so... That was why I wrote gain exactly rather than jump). --Kynde (talk) 07:36, 16 December 2025 (UTC)

- or its mightiest jump in any direction (that doesn't cause it to crash through the Earth) since the escape speed is the same in all directions (relevant xkcd:https://what-if.xkcd.com/68/ ) --178.197.223.163 09:21, 16 December 2025 (UTC)

The only two variables are rjf and M, so plotting a 2 axis graph plotting the relationship between M and rjf should be possible. Zabadoh (talk) 08:20, 16 December 2025 (UTC) [You sign after your contribution]

As frogs usually collect on the surface of worlds [citation needed], the *surface* escape velocity is most important. The crossover point for a planet with earth-like density (5515 kg/m³) is 2.6km, above that, the rjf falls below the surface, and the planet can accumulate frogs. Smaller bodies are, however, usually less dense; an interesting borderline candidate is Chicxulub, which had an rjf of 3-4km, and a radius of 5-6km so could have just about held onto its frogs, for a while at least. JeffUK (talk) 10:04, 16 December 2025 (UTC)

It would be interesting to look at the Rjf values of a frog, to consider where new limits are put upon the frog for M-masses that aren't totally dominating the scenario of "frog leaves mass"... 82.132.237.93 11:03, 16 December 2025 (UTC)

I interpreted it as a reference to the Mark Twain short story The Celebrated Jumping Frog of Calaveras County. Gustaveeiffel314 (talk) 12:25, 16 December

I also suspected an allusion to Twain's short story, but then I read it at archive.org/details/celebratedjumpin00twai and found no parallels. The earth's radius wasn't the problem, it was 5 pounds of quail shot. That frog didn't land with a "plop" but "as solid as a gob of mud." There is no mention of "champion" in the story. The 1865 population of Calaveras County (post Gold Rush) was down below 15,000. That is, the frog shown in #3181 probably came from somewhere else that really knows how to breed frogs with muscular legs, maybe France. Before I risk overthinking this, I'm going to conclude that #3181 is not a Twain reference. Bismuthfoot (talk) 14:37, 16 December 2025 (UTC)

What's with all that text in the incomplete explanation warning box? It seems like it belongs in the discussion. Barmar (talk) 15:05, 16 December 2025 (UTC)

Erm, the current text has a statement that rjf < 4.5m/s for other planetary bodies. Seems like it is mixing measurements, a radius would be a distance, not a velocity. It might be trying to say that other planetary bodies have an ESCAPE VELOCITY of more than 4.5 m/s, so jumping frogs on the surface of those planetary bodies couldn't get out of that planet's gravity well. ~~ 57.140.32.36 (talk) 15:53, 16 December 2025 (please sign your comments with ~~~~)

- Don't recognise your statement (until I check the current state of the main explanation), but a radius can be defined as a vector, as can a velocity. Pretty sure that's not what it says (or should be saying), but there is a possible interchangability if analysed in the 'right' way. 82.132.237.93 17:00, 16 December 2025 (UTC)

- (ETA: Nope, can't see where "the current text has a statement that rjf < 4.5m/s for other planetary bodies" - Unless I'm missing some obscure reference to it that you're not!) 82.132.237.93 17:04, 16 December 2025 (UTC)

It might be worth pointing out that frogs found on the surfaces of other planets in our solar system will have other reasons for not being able to jump to escape velocity (eg., they are no longer alive) 2A09:BAC2:6188:123C:0:0:1D1:CF 01:20, 17 December 2025 (UTC)

- A frog does not have to be alive to jump, it could be a mechanical one. SDSpivey (talk) 02:44, 17 December 2025 (UTC)

- A mechanical frog couldn't be a champion jumping frog though, because only biological frogs are allowed to compete. 76.22.93.146 03:38, 17 December 2025 (UTC)

- So perhaps not a champion frog, but rather a frog built by a champion frog builder? (Runners-up for champion frog builder include both of the champion frog’s parents.) KelOfTheStars! (talk) 21:00, 17 December 2025 (UTC)

- A mechanical frog couldn't be a champion jumping frog though, because only biological frogs are allowed to compete. 76.22.93.146 03:38, 17 December 2025 (UTC)

I disagree with the point about the flawed argument of frogs all being on earth. With a simple assumption that no aliens have transported a frog off world, basic taxonomy says that anything resembling a frog on another planet would infact not be a frog and would be a result of convergent evolution. I also think that aliens moving stuff around is not a common inclusion in physics formulas. So perhaps still falwed but not as strongly flawed as implied in the main text. 2001:14BA:A086:FF00:39D0:B88:A6EF:5F9C 08:28, 17 December 2025 (UTC)

- That doesn't negate the point that if a frog was loose in space, it could be trapped in the gravity well of another planet and end up there rather than Earth. The 'theory', in the way it is expressed, contains the hidden implication that frogs start off floating around freely - not on any planet. 82.13.184.33 09:34, 17 December 2025 (UTC)

- There's always the theory of Panfrogspawnia... ;) 82.132.238.175 11:59, 17 December 2025 (UTC)

Hmm.. How about frogs taken to the ISS for experimental purposes? Surely there's one or two if those? 2A00:23C8:253C:101:5BC5:789F:56FB:A042 08:42, 17 December 2025 (UTC)

- From a general relativity point of view the ISS is not really different from the surface of Earth. In fact if you factor in the Jumping Frog Radius you can redefine the surface of Earth as englobing the orbit of the ISS, as, basically, the "surface of the Earth" is just some stuff jumbled together by gravity, so this technically applies to the ISS as well. 78.241.48.142 11:06, 17 December 2025 (UTC)

- The ISS isn't in a constant frame of reference to the Earth's surface. If you want to redefine the surface of the Earth as being the "spherical ISS-like sphere" then that's a different body (loosely akin to the differences between analysing static and rotating black holes, for schwarzschild radius purposes).

- In fact, you have to do most of the work to get to ISS's orbit (far more than 'merely' getting to its altitude), 9.4km/s (ish). You only need about ~1.7km/s more to escape Earth entirely.

- Not quite within Champion Frog reach, of course. Or not a single CJF, but by using a lot of them, and by careful configuration of a stack of those frogs using the

RocketFrog Equation, you could probably get at least one small frog to entirely leave Earth's gravitational influence. As you might from Earth, but you'd need a lot more frogs. 82.132.238.175 11:59, 17 December 2025 (UTC)- You also all forget that without boosts using fuel the ISS will end up back on the surface of the Earth with the frogs (burning up in the process but the relics would be on Earth again). And it is not said that any frogs could not be outside of Earth but they would be within the rjf radius, and thus be on their way back to this surface, as is the ISS. --Kynde (talk) 19:59, 17 December 2025 (UTC)

- And if someone's using a 'frog stack', from the ISS, then the initial lower-stack-hop (and the quick return of the stage-1 frog(s) once the stage-2 one(s) hop, and so on, at least until they start drifting past it instead) will probably initiate an even sooner deorbit of the ISS. 78.144.255.82 22:00, 17 December 2025 (UTC)

- You also all forget that without boosts using fuel the ISS will end up back on the surface of the Earth with the frogs (burning up in the process but the relics would be on Earth again). And it is not said that any frogs could not be outside of Earth but they would be within the rjf radius, and thus be on their way back to this surface, as is the ISS. --Kynde (talk) 19:59, 17 December 2025 (UTC)

Different calculations apply to the champion jumping frog from Calaveras County, which is filled with lead shot.😜 //The Celebrated Jumping Frog of Calaveras County// 2A01:599:440:4562:8B23:E990:3BF3:6259 22:27, 17 December 2025 (UTC)

Are the escape velocity figures in that table...even remotely accurate? For instance, the table claims Eris's escape velocity is 4.43 meters per second, while Wikipedia says 1.38 kilometers per second. (Also that Eris is ~4.43 orders of magnitude brighter than its moon, Dysnomia, in infrared. Hopefully that's unrelated.) GreatWyrmGold (talk) 23:46, 17 December 2025 (UTC)

- I was wondering about that myself, but you got here a few minutes before I did. BunsenH (talk) 23:54, 17 December 2025 (UTC)

- I can't even hazard a guess as to where those numbers could possibly come from, besides hallucination. Sedna's mass isn't known (since it has no known moons, it can't be calculated) but it is significantly smaller than the others (c. 500km radius compared to 715 (Makemake) 790 (Haumea) or 1163 (Eris)), and the ones that are known have rjf radii, in light seconds, of 55 (Makemake), 86 (Haumea) and 365 (Eris). Their semi-major axes are (respectively) 45, 43 and 68 AU. There is therefore no sort of calculation that I can find, using any of those numbers, or their square roots or whatever, that give anything like the numbers in the table... 2A01:CB08:E6:7000:D0A9:46FC:30BB:E6E3 08:33, 18 December 2025 (UTC)

- I came here for the same reason. Scape velocities in the table are definitively wrong. Escape velocity for Eris is given in Wikipedia as 1.38 ± 0.01 km/s, about three orders of magnitude over the number listed in the table.

- Having such a table is a great idea but we need to correct the maths and add some smaller bodies. Probably some comets will be larger than their jumping frog radius.--Pere prlpz (talk) 10:31, 18 December 2025 (UTC)

- I replaced the current list items with Deimos and Halley's Comet. In general, an object small enough for a frog to jump away will also be minor enough to be unfamiliar to readers unless the object is pretty close to us. EDIT: Jupiter's named Trojan asteroids are all too large. Earth's two known Trojan asteroids don't have known masses, so their escape velocities can't be calculated unless their densities are assumed. BunsenH (talk) 15:26, 18 December 2025 (UTC)

I have looked, but I cannot find out the result of an experiment that had frogs on the ISS a few years ago. Therefore "all the frogs" are not necessarily on the Earth's surface. SDSpivey (talk) 05:10, 19 December 2025 (UTC)

- Ladies and gentleamphibia... have we all forgotten the Orbiting Frog Otolith...? 92.23.2.208 22:11, 19 December 2025 (UTC)

- Unfortunately, Orbiting Frog Otolith never managed to reach the rjf distance for Earth. --206.47.13.28 00:30, 23 December 2025 (UTC)