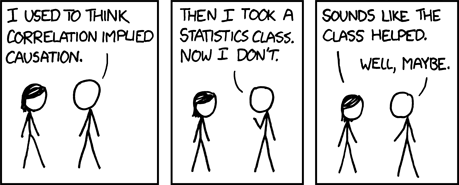

552: Correlation

| Correlation |

Title text: Correlation doesn't imply causation, but it does waggle its eyebrows suggestively and gesture furtively while mouthing 'look over there'. |

Explanation[edit]

This comic focuses on the apparent difficulty people have in understanding the difference between correlation and causation. When two variables (like blood cholesterol levels and heart disease) are positively correlated, it means that as one variable increases so does the other, whereas a negative correlation means that as one variable increases, the other decreases. The human brain is very good at seeing patterns and deducing rules, and the seemingly natural conclusion is that that the one is leading to the other. In the example, that high blood cholesterol causes heart disease. This may well be true. The positive correlation is certainly not an argument against such a conclusion. But it is only one type of evidence and is certainly not proof.

The relationship between diet and blood chemistry and heart disease is a complex one, but simpler examples abound. For example, if you tallied the sales of sunglasses and incidence of skin cancer by region, you would probably find that there is a high positive correlation. That is, in locations where many people buy sunglasses, there are also many cases of skin cancer. Here it would seem silly to believe that wearing sunglasses can cause skin cancer, but this is exactly the same thinking that allowed us to conclude that blood cholesterol causes heart disease. Correlations do have the ability to mislead us. In this example, both sunglasses and skin cancer are directly affected by a third factor (specifically, a climate where many people expose themselves to the sun). In essence, when two variables are correlated it does not provide evidence that one variable has caused the other. All it says is that their trends move in relation to each other. The correlation could be due to causality, but it could equally be due to other factors, or it could even be a random result.

In this situation Cueball is explaining to Megan his realization that correlation is not the same thing as causation. He further explains that his belief changed some time after taking a statistics class. Megan, concludes that the course caused his realization thereby establishing a causation. Cueball's final response of "Well, maybe." is a self-referential joke as there is not enough information to establish causation, only correlation which the class supposedly would have taught him. Being taught something in an academic setting does not necessarily mean a person will readily understand/realize the concept, hence the lack of absolute causation. It could also be a joke on Megan's behalf. Cueball should probably know whether his new knowledge was caused by the course, but he points out that Megan can't be certain about the causation.

The title text plays on two meanings of the word imply: have as consequence, or insinuate. In the statement correlation does not imply causation, correlation is here seen as a person, giving you subtle hints where to look for the cause. This is a metaphor for research, where the correlation must be investigated further, perhaps in a wider scope or with the consideration of more variables, so that the reason for it is understood. For example, Barry Marshall and Robin Warren noticed that the presence of Helicobacter pylori was highly correlated with duodenal ulcer patients. They investigated further. Result: the Nobel Prize in Medicine.

In addition, the title text's reference to waggling eyebrows and gesturing furtively while mouthing "look over there" is possibly a reference to the movie Ferris Bueller's Day Off, in which the character of Cameron Frye tries to alert Ferris that Ferris's father is in the next cab over, and they are about to be discovered ditching school. What Randall is saying with this reference is that Correlation (if it were a character in a movie) is desperately trying to draw attention to Causation without openly stating this intention, and perhaps that correlation is a good place to start when looking for causation.

At the end, Megan suggests that "the class helped" (which is a causation), but Cueball is not sold, exactly because correlation (taking the class and improved understanding of causation versus correlation) does not imply causation (taking the class leads to improved understanding).

Transcript[edit]

- [Cueball is talking to Megan.]

- Cueball: I used to think correlation implied causation.

- [Cueball lift his hand while continuing to talk to Megan.]

- Cueball: Then I took a statistics class. Now I don't.

- [Back to the same situation as the first frame.]

- Megan: Sounds like the class helped.

- Cueball: Well, maybe.

Trivia[edit]

This comic used to be available as a T-shirt in the xkcd store before it was shut down.

Discussion

It is stated that Cueball is doubting, due to his newly found sceptism, which I believe is incorrect.

By stating that "the class helped", Megan is inferring there is a causal relation between Cueball taking a statistics class and him no longer believing correlation implies causation. However, Cueball is replying "well maybe" to indicate there is only a correlation between them, showing he correctly understood the distinction. 173.245.53.104 15:29, 13 May 2014 (UTC)

Another interpretation that explains why the comic is funny is as follows. Cueball replies "well maybe" because he has learned not to infer causation from correlation. But it is also clear that the statistics class caused him to think this way. This pokes fun at a tendency to apply the principle that correlation does not imply causation even when there is direct evidence for causation. 173.245.52.127

The way I see it, it's a paradox. -- The Cat Lady (talk) 22:14, 16 August 2021 (UTC)

Technically, this comic, despite its title, isn't about correlation, but association. As Britannica states, "Although the terms correlation and association are often used interchangeably, correlation in a stricter sense refers to linear correlation, and association refers to any relationship between variables." https://www.britannica.com/topic/measure-of-association. (Also, the second comment should be stating that Megan is implying, not that she is inferring. She did infer, but in "stating," she is implying.) -- Az1950 (talk) 22:58, 11 March 2025 (please sign your comments with ~~~~)

I always just interpreted it as "Now I don't [take the statistics class anymore]." Am I just dumb or -- Augie279 (talk) 03:53, 6 May 2025 (UTC)

- I'm not calling you dumb, but I don't think that interpretation works. To put this abstractly, Cueball said, "I used to [do X]. Then I [did Y]. Now I don't." It would be a strained interpretation to have that mean that Cueball doesn't do Y anymore. Suppose Cueball had said, "I used to get my coffee from Starbucks. Then I learned to brew my own coffee. Now I don't." It would not be possible to take this to mean, "Now I don't learn to brew my own coffee anymore." --172.70.126.36 15:31, 9 May 2025 (UTC)