505: A Bunch of Rocks

| A Bunch of Rocks |

Title text: I call Rule 34 on Wolfram's Rule 34. |

Explanation[edit]

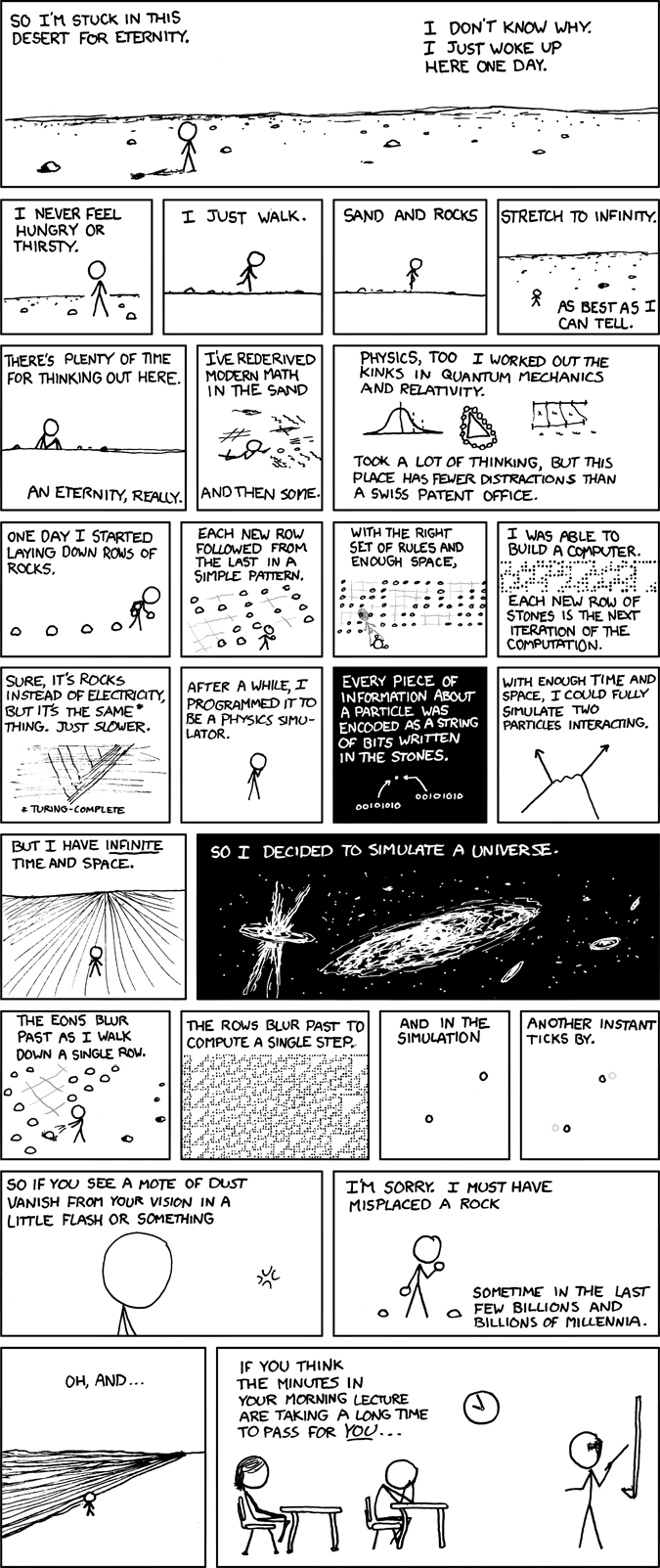

Cueball awakens to find himself trapped for eternity in an endless expanse of sand and rocks. At first, he uses this time to derive all of mathematics and physics, plus more, including quantum mechanics and general relativity. Next Cueball creates a computer that can process any possible function, out of rocks and rules for the interaction between rocks. He then simulates a particle followed by the interactions between particles, followed by the entire universe. The amount of time it takes to simulate the change in the universe merely from one instant to the next takes is extremely long, as the time it takes to update just one row of rocks would be eons, assuming a realistic time to place each rock.

Cueball is using the rocks to build a cellular automaton, a computational model based on simple rules to advance from one state to the next. Certain cellular automata are Turing-complete, which means that they can be used to represent any conceivable algorithm if expanded infinitely, including simulating the physics of the universe. He specifically seems to be running Wolfram's Rule 110, which is capable of universal computation. When using Rule 110 for universal computation, one builds a background pattern, which can be seen in the comic as the pattern of smaller triangles, and then performs computation by sending out "rockets" to collide and interact with each other. Cueball can simulate the functioning of an entire universe because he has unlimited time and space (and rocks).

Cueball then apologizes for any flaws we see in the simulation. This implies that the audience is living in Cueball's simulation, making Cueball essentially God, and that he might make mistakes along the way. The final frame cuts to a classroom where a bored student stares at his hands waiting for class to end. Cueball admonishes the student for thinking that class is lasting forever, the joke being that the boredom felt in a classroom is nothing compared to the boredom that inspires Cueball to spend his endless time toiling to keep the universe moving. Indeed, the minutes of lecture actually took many "billions and billions of millennia" for Cueball to simulate. Another possible explanation is that the entirety of this comic is a fantasy in Cueball’s mind as he zones out during a math lecture.

The Swiss patent office line refers to Albert Einstein, who was employed as a Swiss patent clerk while coming up with his theory of special relativity. This joke is also referenced in 1067: Pressures. Also, there is a standing joke that very few important inventions have come from Switzerland, since the country hadn't been involved in the world wars, and thus has not been part of the weapons race, nor was it a driving force in the preceding Industrial Revolution. In the center of the comic, the binary numbers pointing to the particle are both 42. This is a reference to the comedic answer to the Ultimate Question of Life, the Universe, and Everything from the The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy series.

Cueball mentions that if we see an artifact flutter in and out of reality, he must have made a mistake in the last "billions and billions of millennia." This implies that the small period of time the artifact is present in his time is much longer than our universe has existed. That is a very long time. However, because it was a really long time, the difference could be more than just a small mote of dust disappearing. It is also possible, however, that it took billions of years to simulate an instant in our universe. The line "I've rederived modern math in the sand and then some" is possibly referring to "Surreal Numbers: How two ex-students turned on to pure mathematics and found total happiness" by Donald Knuth, in which a young couple finds themselves stranded on a deserted island (similar to Cueball), and spend much of their time deriving the properties of surreal numbers from a few base axioms.

The title text suggests that Rule 34 should be called on Wolfram's Rule 34. Rule 34 (see 305: Rule 34) is a humorous rule of the Internet that states, "If you can imagine it, there is porn of it. No exceptions." Wolfram's Rule 34 is a cellular automaton. Therefore, the title text says that either someone has made pornography featuring the cellular automaton in question, or someone has used the cellular automaton to produce pornography. Which, of course, Cueball in the comic has, since his universe presumably contains naked people. And literal pornography.

From xkcd: volume 0:

Things simulated in stones in the desert are exactly as real as things simulated in silicon on your computer.

Graphs[edit]

The three diagrams in the "Physics, too. I worked out the kinks..." panel are, from left to right:

- The Normal distribution of the Gaussian curve marking the points that represent a standard deviation of σ and 2σ. This is one of the fundamental building blocks of statistics. In quantum mechanics, particles are viewed as inherently random, therefore the time at which a particle will decay, the position of a particle, and its velocity are all calculated using similar curves. A deviation of at least σ occurs 32% of the time, while a deviation of 2σ or more occurs about 5% of the time.

- The Epitaph of Stevinus, an explanation of the mechanical advantage of using an inclined plane. The inclined plane is one of the six classical simple machines, one of the fundamental building blocks of mechanical and civil engineering.

- The last graph is unknown. It may represent coupled pendulums, length contraction, or a hypothetical solution to something we haven't derived yet.

The graph that represents particle interaction is a Feynman Diagram. This shows the interaction of subatomic particles that collide and exchange some momentum via a photon. The slope of the middle line represents the distance moved and the time lost/gained during the interaction.

Transcript[edit]

- [Cueball is standing in a desert with lots of rocks lying around. He is narrating his own situation. The first panel spans the entire width of the comic. The first line of text is written to the left of him, the second line to the right.]

- So I'm stuck in this desert for eternity.

- I don't know why. I just woke up here one day.

- [The next four panels take up the second line of the comic.]

- [Cueball stands in the desert.]

- I never feel hungry or thirsty.

- [Cueball walks in the desert.]

- I just walk.

- [Zooming out while Cueball continues to walk in the desert.]

- Sand and rocks

- [Zooming far out as Cueball again just stands in the desert. First line of text, above him, is a continuation of the text in the previous panel. The second line is below him.]

- stretch to infinity.

- As best as I can tell.

- [The next three panels take up the third line of the comic. The last takes up half the width.]

- [Cueball is sitting in the desert, in a contemplative position. First line of text above him, the second below.]

- There's plenty of time for thinking out here.

- An eternity, really.

- [Cueball is sketching stuff in the sand. First line of text above him, the second below.]

- I've rederived modern math in the sand

- and then some.

- [Three different graph types are depicted. First line of text above them, the second below.]

- Physics too. I worked out the kinks in quantum mechanics and relativity.

- Took a lot of thinking, but this place has fewer distractions than a Swiss patent office.

- [The next eight panels take up the fourth and fifth lines of the comic. All pictures are the same size.]

- [Cueball is walking along the desert, laying out rocks on a line. Four have been deployed. He is laying down the fifth and has a sixth in his other hand.]

- One day I started laying down rows of rocks.

- [Cueball, with a rock in his hand, continues to deploy rock 16, in a more intricate pattern. There are grid-lines in the sand (5 rows, 6 columns), with each intersection either empty of filled with a rock. No rocks lay anywhere but at an intersection on the grid.]

- Each new row followed from the last in a simple pattern.

- [Zooming out showing even more laid out rocks. Cueball is seen directly from above, and we see his shadow falling on the grid of rocks (7 rows, 14 columns).]

- With the right set of rules and enough space,

- [Continues to zoom further out showing clear triangular patterns (with no rocks) in the laid out grid of rocks. Cueball is not seen. (8 rows, 42 columns). First line of text above the grid, the second line below.]

- I was able to build a computer.

- Each new row of stones is the next iteration of the computation.

- [Zooming far out (no Cueball) with rows intersected by five clear V lines on top of them. The V's are drawn inside each other, with the smallest V at the top right, and the other V's starting just to the right of the previous one, and then continuing the same distance past the previous V, as the total length of the first V. The "*" in the first line of text above this grid references to the footnote below written in a smaller font.]

- Sure it's rocks instead of electricity, but it's the same* thing. Just slower.

- *Turing-complete

- [Cueball stands in a contemplative pose (on a clean white background - i.e. no dessert).]

- After a while, I programmed it to be a physics simulator.

- [A black panel with white drawings and text. A small white dot (a particle) is labeled by two arrows coming of two binary strings.]

- Every piece of information about a particle was encoded as a string of bits written in the stones.

- 00101010

- 00101010

- [A Feynman diagram showing two particles interacting. Two arrows going in and out with a snaking line between them.]

- With enough time and space, I could fully simulate two particles interacting.

- [The next two panels take up the sixth line of the comic. The second panel takes up three-quarters of the width.]

- [Cueball standing before the vastness of the desert, with his programmed lines of rock stretching to infinity.]

- But I have infinite time and space.

- [A black panel with white drawings and text. Depiction of two large galaxies, one with four jets coming out of its center, the other a flat disc. Several smaller galaxies and/or stars are shown around them.]

- So I decided to simulate a universe.

- [The next four panels take up the seventh line of the comic. They are of similar widths.]

- [Cueball is walking by his grid of rocks, lines indicate he has just thrown another rock down in its place. It falls so hard it sinks into the sand that splashes out around it. The 14 rocks above him lie on the grid, four others below this grid have not been used yet.]

- The eons blur past as I walk down a single row.

- [Zoom far far out to show multiple rows of rocks. It is not very clear that there are several triangular patterns (with no rocks) in different sizes in the laid out grid of rocks. There are about 50 rows and 90 columns. There are six large triangles on top of each other at the left edge. To the right, there are three even larger triangles from top to bottom, the one in the middle further to the left than the one above, but further right than the bottom one.]

- The rows blur past to compute a single step.

- [Shows the placement of two particles in the simulation.]

- And in the simulation...

- [The two particles have moved just long enough as to not overlap with their previous positions, shown as an after-image with faint gray lines. The text continues directly the one from the previous panel.]

- another instant ticks by.

- [The next two panels take up the eighth line of the comic. They each take up half the width.]

- [A Cueball-like person (you) observes a mote of dust vanish.]

- So if you see a mote of dust vanish from your vision in a little flash or something

- [Cueball is standing between two rocks on the ground, while holding two rocks, one lifted up to his head. The first line of text is above him. It is a direct continuation of the text in the previous panel. The second line stands below to the right of him.]

- I'm sorry. I must have misplaced a rock

- sometime in the last few billions and billions of millennia.

- [Cueball stands in the "clean" part of his infinite desert, in front of the vastness of his infinity of infinite lines or rocks.]

- Oh, and...

- [A Cueball-like student sits in a classroom with his head in his hands, Megan sits behind him, and a teacher points to the blackboard. A clock shows the time at five minutes to ten.]

- If you think the minutes in your morning lecture are taking a long time to pass for you...

Trivia[edit]

This comic used to be available as a signed print in the xkcd store before it was shut down.

Discussion

- Weird thing with lines in it

Could it have something to do with time dilatation? something like "real" time vs "observed" time (my first comment, hope I did it right) 108.162.241.82 20:49, 18 May 2017 (UTC)108.162.241.82

probably has something to do with relativity -- two objects moving, arriving at different points at the same time, or maybe a diagram of spacetime. 66.202.132.250 16:44, 10 June 2013 (UTC)

It's a Feynman Diagram 206.174.12.203 19:24, 10 June 2013 (UTC) Toby Ovod-Everett

- I did add the incomplete tag because this comic and also the explain is still really complex. More important: People without a proper physics background never will understand. --Dgbrt (talk) 21:01, 10 June 2013 (UTC)

There is a short story called "SOLE SOLUTION" by Eric Frank Russell which is quite similar to the one in the story. Just in case that matters. -- Maob (talk) (please sign your comments with ~~~~)

Re Rule 34 - the point is that this comic _is_ cellular automaton porn (as are the YouTube videos of Minecraft calculators and the like). Rule 34 works, bitches! 141.101.98.241 (talk) (please sign your comments with ~~~~)

Not sure what's incomplete about the explain. 0100011101100001011011010110010101011010011011110110111001100101 (talk page) 22:56, 11 February 2014 (UTC)

Yo calculus is the latin word for pebble! I learned this and had to come straight to this page! ahhh connections! 173.245.50.88 Sawyer Biddle

As it turns out, Rule 110 seems to be a really bad way to simulate a universe- you would be much better off using a Cyclic tag system, since Rule 110 takes dozens of generations and potentially hundreds of cells to simulate one step in such a system, or a more sophisticated cellular automaton, such as Wireworld. --Someone Else 37 (talk) 05:12, 9 March 2014 (UTC)

To whoever objected to panel number references, does what I did with first words fix that? 199.27.128.99 (talk) (please sign your comments with ~~~~)

Well, that's a pretty unfair comparison in the last panel, the protag is immortal after all, if I'm immortal I might do the same thing, but hey we got a much shorter life to live 103.22.201.168 (talk) (please sign your comments with ~~~~)

The diagram to the right of the Epitaph of Stevinus looks like a system of coupled pendula, often used in math physics courses to illustrate Lagrangian mechanics. Also may relate to elasticity theory. See for example here: http://demonstrations.wolfram.com/ThreePendulumsConnectedByTwoSprings. 108.162.221.96 03:23, 12 November 2014 (UTC)

- If this is true (which seems like the most probable solution so far) then what do the symbols inside the boxes represent? 108.162.216.209 (talk) (please sign your comments with ~~~~)

- Spring constants, masses, lengths, etc 108.162.221.220 18:11, 12 November 2014 (UTC)

- The symbols on the top seem to be K and the bottom W. W is often used for angular momentum and K for potential energy. If you are not exactly right you are very close to being so.108.162.216.209 13:45, 1 December 2014 (UTC)

- Spring constants, masses, lengths, etc 108.162.221.220 18:11, 12 November 2014 (UTC)

- The "diagram to the right of the Epitaph of Stevinus", also described as "A weird diagram with lines in it", or "partitioning of phase space into fundamental cells", or " system of coupled pendula, often used in math physics courses to illustrate Lagrangian mechanics", can be described more literally: There is are two horizontal rulers with divisions 13 pixels apart and 17 pixels apart, respectively; and diagonal lines showing the correspondence between the first four markings of the upper ruler with those on the lower. The intervals seem to be labeled. Returning to speculation, I think this suggests an illustration of Length contraction (Lorentz coordinate transformation) in Special Relativity. Mrob27 (talk) 20:22, 28 November 2014 (UTC)

- That seems highly unlikely due to the top labels on this graph. In your explanation they can’t represent anything relevant. Also if this diagram is used to represent spatial contraction, it does not do a good job of it. 108.162.216.209 13:45, 1 December 2014 (UTC)

- I imagined the labels were, top row: O', x', (2x)'; bottom row: O, x, 2x, Δv; or perhaps top row: Δx₁', Δx₂', Δx₃'; bottom row Δx₁, Δx₂, Δx₃, 0.7c. I don't think Randall put enough thought into those tiny squiggles for us to be able to use pixel-counting as a hint to which labels interpretation is more likely… but what of it? We can make up labels that fit any interpretation. I did say "Length contraction (Lorentz...)" was just speculation. I do like the "four pendulums coupled by springs" idea, though the horizontals look too ruler-like to me. It might be better just to say "two horizontal ruled lines linked by some diagonals" ! Mrob27 (talk) 17:00, 1 December 2014 (UTC)

- You are totally right, this one may always be pure speculation. Though I am pretty sure the bottom points are labeled w, the top is by no means clear. 108.162.216.209 20:46, 1 December 2014 (UTC)

- I propose that we change it again, from (current text: "A depiction of length contraction, with two lines of the same length locally but different lengths as one is viewed in motion") to something like "A depiction of length contraction with two rulers in relative motion, or of several pendulums coupled by springs". Or mention the pendula idea first, I don't want to decide. Mrob27 (talk) 02:20, 2 December 2014 (UTC)

- Though it's in panel before that one, there's the text "and then some" referencing going beyond what we currently know in a field - could it possibly be that this is supposed to represent something we haven't derived yet? -- Brettpeirce (talk) 10:44, 2 December 2014 (UTC)

- I propose that we change it again, from (current text: "A depiction of length contraction, with two lines of the same length locally but different lengths as one is viewed in motion") to something like "A depiction of length contraction with two rulers in relative motion, or of several pendulums coupled by springs". Or mention the pendula idea first, I don't want to decide. Mrob27 (talk) 02:20, 2 December 2014 (UTC)

- You are totally right, this one may always be pure speculation. Though I am pretty sure the bottom points are labeled w, the top is by no means clear. 108.162.216.209 20:46, 1 December 2014 (UTC)

- I imagined the labels were, top row: O', x', (2x)'; bottom row: O, x, 2x, Δv; or perhaps top row: Δx₁', Δx₂', Δx₃'; bottom row Δx₁, Δx₂, Δx₃, 0.7c. I don't think Randall put enough thought into those tiny squiggles for us to be able to use pixel-counting as a hint to which labels interpretation is more likely… but what of it? We can make up labels that fit any interpretation. I did say "Length contraction (Lorentz...)" was just speculation. I do like the "four pendulums coupled by springs" idea, though the horizontals look too ruler-like to me. It might be better just to say "two horizontal ruled lines linked by some diagonals" ! Mrob27 (talk) 17:00, 1 December 2014 (UTC)

- That seems highly unlikely due to the top labels on this graph. In your explanation they can’t represent anything relevant. Also if this diagram is used to represent spatial contraction, it does not do a good job of it. 108.162.216.209 13:45, 1 December 2014 (UTC)

- Also, I'd like to point out that all three diagrams unify the theme of "working out the kinks in quantum mechanics and relativity": The first illustrates a region of the bell curve where a particle might occasionally fall if it is about to exhibit quantum tunneling; the second relates to perpetual motion, thus hinting at general questions like "does quantum mechanics or relativity allow us to violate the laws of thermodynamics in any way?", and the third is from special relativity. Mrob27 (talk) 20:22, 28 November 2014 (UTC)

- Having studied (and knowing the fundamentals about what profile is needed to create a device that performs quantum tunneling) I have never seen this graph as a representation of this, and frankly it makes no sense. If this diagram was an energy band the hole or electron would have no need to tunnel to go up or down the energy band as it is a gradual slope. If a device had a profile like this, it would not result in a significant number of tunneling events, especially at the positions that are marked on the diagram. For this to occur there would need to be a peak between the two points, and the points would need to be at similar heights (energy levels). 108.162.216.209 13:06, 1 December 2014 (UTC)

- Yes, you're right: all we know is that it's a bell curve (normal distribution), and mentioning "tunneling" might make the reader think we were saying it is a potential function. I was reading a bit much into it. Why are there two vertical dotted lines at roughly +σ and +2σ? I thought they indicated a "range" as if the graph were illustrating some discussion of things that fall within that range. I also incorrectly remembered what the Epitaph of Stevinus was about, so thanks for the corrections :-) Mrob27 (talk) 16:57, 1 December 2014 (UTC)

- I think we could reasonably add that the function represents a probability distribution of a partial, therefore tying in the quantum aspects. with a minor explanation of the probibility of 1 and 2 sigma. 108.162.216.209 20:46, 1 December 2014 (UTC)

- Yes, you're right: all we know is that it's a bell curve (normal distribution), and mentioning "tunneling" might make the reader think we were saying it is a potential function. I was reading a bit much into it. Why are there two vertical dotted lines at roughly +σ and +2σ? I thought they indicated a "range" as if the graph were illustrating some discussion of things that fall within that range. I also incorrectly remembered what the Epitaph of Stevinus was about, so thanks for the corrections :-) Mrob27 (talk) 16:57, 1 December 2014 (UTC)

- Having studied (and knowing the fundamentals about what profile is needed to create a device that performs quantum tunneling) I have never seen this graph as a representation of this, and frankly it makes no sense. If this diagram was an energy band the hole or electron would have no need to tunnel to go up or down the energy band as it is a gradual slope. If a device had a profile like this, it would not result in a significant number of tunneling events, especially at the positions that are marked on the diagram. For this to occur there would need to be a peak between the two points, and the points would need to be at similar heights (energy levels). 108.162.216.209 13:06, 1 December 2014 (UTC)

The bigger picture that's missing on this explains it that this comic seems to suggest that Cueball is God, as in being stuck in Eternity who happened to build a simulated universe, which we all live in. Seeing how he addresses the reader "So if you see a mote of dust vanish from your vision in a little flash or something I'm sorry. I must have misplaced a rock sometime in the last few billions and billions of millennia." {{141.101.105.238 10:25, 12 November 2014 (UTC)}}

- I understand that English might not be your first language, but please clarify. The explanation covers Cueball being godlike. How can we add something that is already covered? Do you require further detail? Are you disagreeing with this assessment? Are you considering this observation irrelevant as your summary for your first comment "added not about Cueball being God" seems to imply? If so why?108.162.216.209 17:57, 12 November 2014 (UTC)

- nm. I blatantly overlooked the exisiting sentence in the explanation. i blame the layout of this page. inline text that spans the whole available screen width is not pleasant to read on large displays ;) ...as for my English... the confusion stems from my bad keyboard/typing. it was meant to read "added notE about Cueball" for instance, or "as in A being stuck". 141.101.105.233 08:15, 13 November 2014 (UTC)

- you could shrink your window and display narrower lines of text(?) -- I guess it comes down to preference for masochism(?)... idunno. I think one of the most confusing parts of your question (and which may have contributed most to the ESL idea) is "missing on this explains it that...". Also, "as in being stuck" makes more sense than "as in a being stuck", though it seems you're suggesting otherwise (?) and I don't see any text mentioning added not(E) about Cueball) -- oh wait; is this a troll? -- Brettpeirce (talk) 15:14, 14 November 2014 (UTC)

- nm. I blatantly overlooked the exisiting sentence in the explanation. i blame the layout of this page. inline text that spans the whole available screen width is not pleasant to read on large displays ;) ...as for my English... the confusion stems from my bad keyboard/typing. it was meant to read "added notE about Cueball" for instance, or "as in A being stuck". 141.101.105.233 08:15, 13 November 2014 (UTC)

Who or what is Nugui and why is it relivent.108.162.216.209 17:57, 12 November 2014 (UTC)

is randall not assuming that his universe (and by implication ours) is finite? if not, one iteration of the machine would still take infinite time. --141.101.98.201 12:42, 26 November 2014 (UTC)

- I think it's good enough to assume that the universe is finite, but really really huge. Hypothesizing that adding one particle to the model requires twice as many cells in the cellular automaton, that means that Cueball's cellular automata rows could be about 2^(10^80) cells long, allowing simulation of a physics system containing 10^80 particles. Of course, each planck-time would require 2^(10^80) steps of simulation in the CA. If 10^80 isn't big enough for you, then just make it 10^1000 or Graham's number, or anything finite. Mrob27 (talk) 16:57, 1 December 2014 (UTC)

- Don't forget that Rule 110 has 000 -> 0. Cueball can just add columns on either side as his universe expands, consequently taking more and more time to compute steps as the number of columns increases. 108.162.216.42 (talk) (please sign your comments with ~~~~)

Did anyone notice that the binary numbers pointing to the particle are both 42? 108.162.241.16 19:26, 27 November 2014 (UTC)

Just as a curiosity -- there is a somewhat similar concept in "Permutation City", a book by Greg Egan. 141.101.88.211 (talk) (please sign your comments with ~~~~)

- And dust is probably a reference to Dust Theory: http://gregegan.customer.netspace.net.au/PERMUTATION/FAQ/FAQ.html 141.101.98.187 (talk) (please sign your comments with ~~~~)

I don't understand how it's possible to simulate a universe this way. Assuming that quantum mechanics is correct, and some forms of particle decay are truly random, wouldn't it be impossible to simulate this with a purely deterministic system? KingSupernova (talk) 15:30, 1 December 2015 (UTC)

- The universe Cueball is simulating would have to conform to digital physics. I can't speak about the fine points of quantum mechanics, but observably random events in a simulated universe could be the result of a pseudorandom number generator with a very large state. Srimech (talk) 23:37, 16 February 2016 (UTC)

This is definitely my favorite comic. I just really love it - I wish there was a book or something about it that was more in depth. --108.162.219.5 14:32, 5 June 2016 (UTC)

- Yeah. Wow. Just... Wow. I would be so interested if this were somehow true. I just wish he could occasionally figure out how to mess with our retinas by spontaneously flipping bits in order to make us see a representation of him. That would be awesome, right? If I can make my own universe, well... I would do that. Also, I love this guy, real or not. That's right, Jacky720 just signed this (talk | contribs) 16:10, 5 January 2017 (UTC)

- Totally. Definitely one of the best XKCD comics ever. 42.book.addict (talk) 19:30, 7 February 2024 (UTC)

I was thinking the whole "eternity in a wasteland" was just a Calvin and Hobbes type fantasy that the bored student conjured up to describe how he felt about this class. ~~ Jelsemium

This still isn't anywhere near as big as 3^^^3. Mathematicians are very good a making big ass-numbers. ~~ Schrodinger's Wolves

There should be a short story about this. Fav comic by far, and got me interested in philosophy lol --162.158.62.181 19:13, 17 July 2020 (UTC)

You can make a religion out of this! 172.68.134.28 13:15, 29 July 2023 (UTC) (actually by Bill Wurtz, not the IP)